Mark Roy / Flickr / License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/deed.en

Mulgana Mia dancers, Carnarvon civic center.

ALICE SPRINGS, AUSTRALIA – It has been 22 years since a major report by the government here found a shockingly high death rate for indigenous people locked up in Australia’s prisons and jails.

The Aboriginal Deaths in Custody report detailed myriad problems in the relationship between indigenous people and the criminal justice system here.

Twenty years later, in 2011, another report, Doing Time -- Time for Doing showed not only that little had improved, but that some issues, particularly those involving young indigenous people and crime, had grown even worse.

One in four people in prison is indigenous – of Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander descent – despite the fact that they make up only about 3 percent of Australia’s total population of 23 million. For young people, it is even worse: They make up more than 60 percent of the detained youth population, but represent only 4.2 percent of all Australian young people.

“This situation is a national disgrace,” the 2011 report says. “All governments including the commonwealth, states and territories have failed to address this problem.” It found that the recommendations of the Australian Deaths in Custody Royal Commission were simply not implemented properly.

Steve Maude is a youth worker who has been helping disadvantaged groups, including indigenous children, for 25 years. For the past 18 months he has been working in Alice Springs, in central Australia, focusing on education re-engagement projects with Aboriginal youth.

“The issues are deeply embedded,” says Maude. “The reality is that there is more going on in communities than just this issue of justice.”

The broad underlying factors contributing to the overrepresentation of indigenous youth in the justice system range from police relations to health issues and a lack of education or inadequate housing, entrenched poverty and a lack of employment opportunities.

Associate Professor John Bradley is deputy director of the Monash Indigenous Centre, undertaking research that focuses on the Yanyuwa people, who live in the southwest of the Gulf of Carpentaria in the Northern Territory. Bradley raises an issue that was highlighted in the Doing Time -- Time for Doing report; current systems over-generalize the issues faced by indigenous Australians.

“One size is not going to fit all … what’s good for where I work isn’t necessarily good for somewhere else,” he says.

This is true nationwide. There are several hundred indigenous groups across Australia, each with their own cultures and traditions and their own concerns. Particular areas may be youth suicide hot spots, such as the community Bradley works in.

Wayne Bell, who works with troubled indigenous youth in the Heywood area, about 220 miles west of Melbourne, also speaks of this issue. “The community down in the southwest where I work, we can’t be involved in telling Geelong [50 miles southwest of Melbourne] how to treat their kids; we don’t want to be telling the organizations in Warrnambool [165 miles west of Melbourne] what to do.”

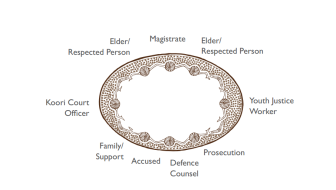

Courtesy of the Children’s Court of Victoria.

A map demonstrating where various parties sit in the traditional Koori Court. Established in 1989 for indigenous defendants, it involves family and community in the process, so sentences can meet both judicial and cultural needs.

Bell has worked and lived in Heywood all of his 58 years, and is a client services officer for Victorian Aboriginal Legal Services. He has worked on the Aboriginal Community Justice Panel for the area, and the Koori Court, a division of the magistrates' court established in 1989 for indigenous defendants. It involves family and community in the process, so sentences can meet both judicial and cultural needs.

Each community has its own particular problems. There are places of high unemployment, places with poor quality housing, places where there are an increased number of females in the justice system, others with specific health issues. Some places may have greater barriers to children participating in the school system, beginning with preschool, putting indigenous children at a disadvantage from their very first day of school.

Indigenous people are statistically more likely to have to deal with all of these issues.

Image courtesy of the University of Melbourne School of Population and Global Health.

Jane Freemantle an associate professor at University of Melbourne.

“Early contact for Aboriginal kids with the juvenile justice system is on the causal pathway to very poor outcomes, but if you look at the antecedents to that they are all possible to ameliorate,” says associate professor Jane Freemantle, of Melbourne University.

Freemantle has focused her career on indigenous health, particularly for children, young adults and communities. She makes it clear that within Aboriginal communities, everything from health to crime is interconnected.

Prevention is important to the stability of indigenous communities because of disparities in indigenous and non-indigenous populations. Half of all the indigenous population is younger than 22, a demographic that is growing at twice the rate of the non-indigenous population in the same age bracket.

It is easy to see exactly how devastating the overrepresentation of indigenous youth in juvenile detention can be, on both a community and a national level.

The issue of imprisonment is a long-debated one. Punishment versus rehabilitation in the criminal justice system is particularly relevant; juvenile detention, from a human rights perspective, is supposed to be a last resort.

It does have more of a focus on rehabilitation than the adult criminal system but, says Freemantle, it’s not good enough.

“By the very nature of the incredible recidivism rate, the revolving door of people coming in bears testament to the fact that the rehabilitation process within the criminal justice system is appalling. And particularly in the juvenile justice system,” says Freemantle.

There are strong links evident between the disproportionate rate of indigenous juveniles in detention and the rate of indigenous adults in prisons. However, there is a lack of access to data showing the link between juvenile convictions and adult convictions in the indigenous community. Freemantle assumes there is data, “but it shows a real failure if [the government] presents it”, as she says it would undoubtedly prove that our systems are not effective.

Image courtesy of Monash University.

: Bronwyn Naylor, a lawyer and a criminologist working with the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University.

Dr. Bronwyn Naylor is a lawyer and a criminologist working with the Castan Centre for Human Rights Law at Monash University. Her work examines issues surrounding prisons in terms of legality and human rights, focusing on prison experiences. Naylor says that “prisons are so incredibly damaging, to both the person themselves and their family … being institutionalized, losing any capacity to make choices; being in an environment that tells you what to do all the time, and gives you no choices, that’s really damaging within itself”.

Naylor says that despite the differing sentence lengths typical in justice systems across the globe – from decades in the United States, to months in Scandinavian countries – there is no evidence that long prison terms reduce the crime rate.

“Countries use imprisonment as a political choice, not a choice about what actually works,” says Naylor.

She describes the current Australian system of imprisonment as “disproportionate punishment … any country that has done research on this agrees that it is both harmful and it doesn’t work, and yet governments continue to say this is what we have to do.”

Naylor says she has anecdotal evidence that supports the effectiveness of alternative programs such as diversions and community supervision, rather than imprisonment.

“There are lots of systemic issues around why indigenous people get picked up in the first place and also why they offend more in the first place in some instances, all of which just need to be undone further back. Prison is just the worst way to deal with it,” Naylor says.

Steve Maude, the youth worker from Alice Springs, criticizes the inflexibility of funding that puts youngsters into rehabilitation processes without fixing problems at home.

“It costs $80,000 a year for a kid to be in juvenile detention up here, more in the cities, I think around $92,000. There has got to be a better way to spend that money. If the family isn’t being supported, what sort of home do [kids] have when they come out, back into a dysfunctional family?”

Bradley agrees, outlining a need for programs to support both families and children in regional communities.

“What I’ve seen in my own experience is kids coming out of jail to more of the same. There is nothing in the communities.”

Recidivism is a big issue, says Bell, and is often a combination of the environment children go back to once out of incarceration, and the environment they experience while in detention.

Bell, based on his extensive experience with the system, says he “can’t remember a young person, more than a couple at least, that have gone into juvenile justice and haven’t gone back.”

The attitudes of community are vital in attempts to keep young people engaged and out of trouble. But as Bell outlines, sometimes it doesn’t quite stick.

“I’ve been into the police station for four nephews who’ve lost their license drink-driving, under six months after I had to identify one of their friends and one of the people that I knew as an ex-client, dead, for drink-driving.”

“My cousin got stabbed in the heart in a fight … at his funeral they had to stop people getting up and talking about him. The service at the church went for an hour and a half. But that night, five or six fights broke out over drugs. They don’t learn.”

An issue Bell says resonates is the differences between a strong home and a broken one.

The Doing Time - Time for Doing report identifies family dysfunction as a strong contributor, alongside the community and cultural implications of these incidents.

Maude says it’s evident that the current systems leave gaps. “The obvious failures are in regional communities … [The Northern Territory] is the wealthiest area in the country in terms of funding. Seventy per cent of the funding in the area is aimed at health and education. Billions of dollars are thrown at the issue,” says Maude.

But he says despite the influx of funding, many of the current systems are generalized from other models used across Australia: schooling techniques, for example.

Bradley agrees. “The idea of compulsory schooling up until the age of 16 as it is across Australia is inappropriate for remote indigenous communities. If an indigenous male has come of age, he’s had the ceremony, in his head he is a man in charge of his own destiny, not a child in a classroom who takes orders from a female teacher,” he says.

“What is being challenged here is the issue of identity.”

Bradley traces this complexity back to the original dispossession of the Australian colonization process.

“If we look at where I work, in the Northern Territory, in one of the languages that are still spoken there are three different words that are still used today to describe the police. One literally translates as poisonous or deadly ones, bitter ones, or those that carry chains,” says Bradley.

This ill feeling towards law enforcement is a trend Bell’s work tries to counteract. He says these sorts of programs, integrating cultural awareness and an exchange of respect with local law enforcement, have proven to be an excellent way to increase community cohesion.

In the Heywood area he has worked on projects involving police officers and juveniles building trust and familiarity, from being partners in outdoor education events, to indigenous youth leading a cultural awareness induction for officers in the area. Bell says this shared experience creates a mutual respect in the area; police in Heywood “don’t go kicking the door down”.

Comprehensive programs focusing on health, education and community are slowly showing results, but it’s not a universal solution. Bell says a typical offender would have an average of 12 people – legal services, youth workers, counselors, health practitioners – working on their case by the time they have been through court: “Juvenile justice bends over backwards to assist young people.”

But despite the wealth of resources directed at these problems, they still occur with alarming regularity, fueled by the complexity of underlying issues yet to be addressed.

Efforts are strengthening though. Bell says: “We’ve got more passion than ever that our people don’t get into trouble.”

Kaitlin Morris has just completed her BA at Monash University in Melbourne with a double major in International Studies and Journalism. She is passionate about social justice and using her skills to give voice to those who deserve their stories told. Kaitlin will be undertaking her postgraduate studies in journalism.

Series Editor: Corinna Hente, editor of Monash University's journalism website, mojo.

Pingback: The deep, systemic problems within Australia's juvenile justice system. — The Good Men Project