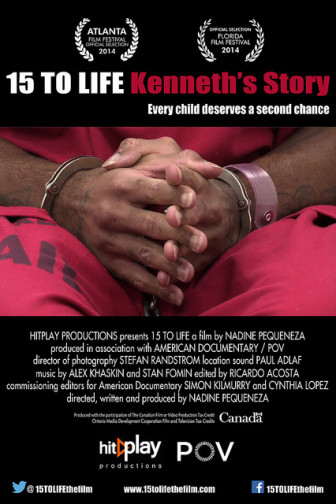

Courtesy HitPlay Productions

Kenneth Young at his resentencing hearing, with his mother and niece in the background.

Kenneth Young, shackled in a chair and wearing a red prison jumpsuit, recalls the unthinkable.

“Everything happened so fast,” he says.

A barbed-wired gate outside the Florida prison closes, before the scene shifts back to Young, on the inside.

“They was like, ‘Well, Mr. Young, you know, you not going home no more. You gonna die in prison.’ I’m like, ‘Who gonna die in prison? I ain’t dying in prison.’ So I was in denial because it happened so fast. It’s like one day, I’m 15 years old and I’m in society. And the next I’m not, and you telling me I ain’t never gonna go home?”

So begins “15 to Life: Kenneth’s Story,” a riveting PBS documentary tracing Young’s quest for release from prison after he was sentenced to four consecutive life terms without parole for his role in four armed robberies of Tampa-area hotels in June 2000.

Young would tell a public defender — and years later, a judge at a resentencing hearing — that his mother’s then-24-year-old crack dealer had threatened to kill her unless the boy helped rob the hotels. The dealer, Jacques Bethea, who had a long criminal history, made the threat because Young’s crack addict mother had stolen drugs from him, Young said.

Bethea planned the heists and brandished the pistol — and during one of them was talked out of raping a female victim by Young. Nobody was seriously injured during the month-long robbery spree.

Still, Young, who had never had a serious scrape with the law, was tried under Florida law as an adult and condemned to die in prison.

Through courtroom footage of a 2011 resentencing hearing, interviews with Young, his attorneys, his guilt-ridden mother as well as law enforcement officials, victims of the robberies and a retired prison warden, “15 to Life” provides a penetrating look not only at Young’s case but also at the practice of sentencing juveniles to life without parole.

Attorney Paolo Annino, the co-director of Florida State University’s Public Interest Law Center, and his law students at the center began working on Young’s case about seven years ago.

By then, Kenneth Young had exhausted all appeals and post-conviction motions, but the landmark 2010 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Graham vs. Florida rekindled hopes for him. In Graham, the court held that sentences of life without the possibility of parole for juveniles convicted of non-homicide crimes violate the Eighth Amendment’s prohibition against cruel and unusual punishment.

“So it really took the United States Supreme Court to say enough of this, enough of this barbarism,” Annino says in “15 to Life.”

Annino argued at the resentencing hearing that Young should be set free after 11 ½ years in prison, noting that he had matured, been rehabilitated, served as a model prisoner and earned a GED (even though the state wouldn’t pay for his education because he was a lifer).

“There’s no point in keeping him in prison. What’s the point? He’s been rehabilitated. We can prove that,” Annino says.

While serving his sentence, Young was cited for only one infraction — not making his bed on a Saturday morning.

Annino pointed out that Bethea had received one concurrent life sentence, a much less extreme sentence than Young’s.

“And we find that around the country, juveniles are being punished much harsher than adults,” Annino says.

The documentary provides some other sobering realities: The United States is the only country in the world that routinely condemns children to die in prison. African-American youths like Young are sentenced to life without parole 10 times more often than their white peers. More than 2,500 people convicted as juveniles are serving life sentences in the United States.

“15 to Life” moves easily between such revealing national perspective and Young’s arduous personal path.

His father died before his first birthday, and his mother, Stephanie Young, was a crack addict for 19 years who routinely neglected Young and his older sister. Young grew up in a violent and poverty-ravaged section of North Tampa known as “Suitcase City” because of the transience of its residents, and his family moved frequently.

As a 2 ½-year-old, he once left his mother’s apartment and wandered over to a neighbor’s home. He dropped out of school as an 11-year-old and helped care for his sister’s two babies.

Young never denied his role in the robberies, but said at the resentencing that hearing he had been rehabilitated and deserved to be freed:

“I have lived with regret every day. ... I have been incarcerated for 11 years and I have taken advantage of every opportunity available for me in prison to better myself,” he said.

Courtesy HitPlay Productions.

Kenneth Young’s neighborhood in North Tampa, known as Suitcase City.

He told the court: “I am no longer the same person I used to be. First Corinthians, Chapter 13, Verse 11 says, ‘When I was a child, I thought as a child. ... When I became a man, I put away all childish things.’”

He then apologized to his victims in the courtroom.

Showing balance, the film not only includes footage from the judge and prosecutor but also quotes testimony from a woman who was a victim of one of the robberies, saying, “As much as I know [Young] wants to be released, I'm not ready to have him walking around my neighborhood.”

Young’s mother, who is now clean, expresses regret and sorrow for not being a better mother to him because of her crack addiction.

“I know the judge has a heart,” Stephanie Young says in an on-camera interview. “I’ve prayed and I’ve asked for forgiveness on behalf of me and my son.”

At the hearing, she tells Judge Daniel H. Sleet of Florida’s 2nd District Court: “Please, your honor, help me put my family back together. Please forgive me. I know as a mother my son would never come back through your system again.”

But the judge appears unmoved by Young’s progress or pleas for mercy.

Sleet congratulates Young on his diploma and says his progress demonstrates that his incarceration was “appropriate and effective” but rebukes him for blaming Bethea for his conduct.

He tells Young releasing him “would be an award, a gift that you will not get from this court,” adding: “You will not get it, sir, because you do not deserve it. I heard your statement. I believe that you have some remorse. I believe that you’ve been rehabilitated. But I’m listening to these victims, sir, and I do not believe that this court should rely on your prison conduct thus far. Sir, this is about personal responsibility and accountability.”

Sleet sentences Young, 26 years old at the time, to 30 years in prison, with credit for time served, and 10 years of probation.

Annino, the leader of Young’s defense team, told JJIE he plans to petition a federal court in Florida to vacate Young’s sentence, arguing Sleet had not given any weight to Young’s rehabilitation, as required by Graham. (The Florida state Supreme Court refused to hear the case in 2013 after Annino argued Sleet had not adequately considered Young’s rehabilitation.)

For his part, Young expresses astonishment over the judge’s decision.

“I had showed from the time I’m 14 years old all the way to the time I’m 26 I have matured and everything,” he says in the film. “I thought that that would mean something. He just basically told me that don’t mean nothing.”

Young says he endured some of the worst prisons — with gangs, violence, rapes.

“And I survived through all that, and he like, ‘That don’t mean nothing. You showed that you rehabilitated, but I’m still gonna send you to this.’”

Still, the possibility of release gives him hope, Young says: “I was supposed to die here. I got hope at the end. I see some light. You gotta take that light that you see and make that light brighter by continuing to fight with your case. I’m gonna fight for what I believe in. I believe I changed. I believe I showed remorse. I believe I matured.”

Richard Lie

Producer/Director Nadine Pequeneza

JJIE asked Nadine Pequeneza, the director and producer of “15 to Life” (and a Canadian who lives in Toronto), to talk about the film. Edited excerpts of the interview follow.

JJIE: How did you learn of Kenneth’s case and what inspired you to do the film?

Pequeneza: I was first attracted to the issue of juvenile life without parole when I learned that this was a sentence. I was astonished because we don’t have anything even approaching that in Canada. In Canada, if a child commits a first-degree murder, it’s not uncommon for them to get a 10-year sentence and be eligible for parole in seven years, and they also stay in the juvenile system. So they’re not transferred into the adult court, and the judges are instructed to consider all of those things that the U.S, Supreme Court has recently said judges should be considering: the child’s age, maturity, the circumstances, peer pressure, adult influence. So all of those things are considered in Canada. The child is sentenced in juvenile court. And in most cases, they’re allowed to serve out their sentences in a juvenile facility so they’re not automatically transferred to an adult prison when they turn 18.

I started to research under what circumstances juvenile life without parole happens in the United States, and then I found out that the U.S. Supreme Court had recently released the Graham decision. That was in 2010. So my research started in 2011. And so when I found out about the Graham decision, I thought it was an opportunity to look at efforts to reform the use of this sentence, recognizing that it was unjust — in view of what the U.S. Supreme Court said: cruel and unusual punishment. And so I started looking for cases that were going to be going forward either in a resentencing hearing or before a parole board. I came across Kenneth’s case because he had applied for clemency and was denied in 2009. I was really attracted to Kenneth’s story because I thought it was exemplary of the majority of kids ending up in that circumstance: He’s African-American. He comes from a poor neighborhood. He was neglected and abused as a child. And he also committed his crime with an adult. So all of those things are very common. We see these patterns in these children that receive this very harsh sentence, and so I thought by focusing on Kenneth, people could get a sense of the broader issues, but also get the opportunity to get to know an individual. I think so often when we hear about these cases, we only hear about the crime, the one incident that led to the sentence, but we don’t really understand who these children are or where they come from, what their situation is, how they grew up.

JJIE: How much does Young’s case exemplify the characteristics the Supreme Court cited in Graham and Miller vs. Alabama, the 2012 Supreme Court ruling that mandatory sentences of life without parole for juveniles violate the Eighth Amendment?

Pequeneza: I think in many ways Kenneth’s case exemplifies the problems the U.S. Supreme Court cited in treating children as adults. He was definitely under the influence of an adult. He grew up in very difficult circumstances where he didn’t have the supervision, much less a positive role model to follow. He lived in an area where crime and drugs were common. He grew up in conditions where he was in three different schools. So he had learning difficulties and grew up in an impoverished neighborhood. And so all of those things that the court pointed out which should be taken into consideration when you’re sentencing a child for these serious crimes — Kenneth is certainly representative of those things. Then in terms of allowing for reasonable opportunity to obtain release based on rehabilitation, Kenneth also exemplifies that. Over 11 ½ years in prison, he had one infraction for not making his bed one morning. And so he’s a model prisoner. So these are the types of things that the U.S. Supreme Court was saying should be taken into consideration.

JJIE: Why do you believe it is so important to try children in the juvenile justice system, as opposed to in the adult criminal justice system?

Pequeneza: The Graham and the Miller decisions really make the same point — that is, that children are different than adults physically, mentally and emotionally and that has to be taken into account when you’re sentencing them. I’m hoping the impact of those cases will be a rethinking of how we treat children when they’re in the juvenile justice system, and a re-emphasis, a refocusing on rehabilitation where children are concerned when they commit crimes, even serious crimes, because we’ve seen that children do have a remarkable capacity for rehabilitation and change. The Supreme Court also recognized that culpability isn’t the same for a child as it is for an adult because of those developmental differences. So what I’m hoping is that it makes us rethink about how we treat children in the justice system and that we keep them in the juvenile system and we focus on rehabilitation instead of punishment.

The United States was the first county in the world to establish a juvenile justice system, and it did that because it recognized that children have the ability to be rehabilitated, that there was good success, good outcomes if they were given the proper supports and programs and guidance. The country moved from one side of the pendulum and swung completely to the other side. We see now with these U.S. Supreme Court decisions and resulting legislation, what's happening around the country is that it’s starting to swing back in a way that recognizes children for who they are: children. There’s so many things that we restrict children from doing because we recognize that they don’t have the same maturity as adults and the same capacity for decision-making and understanding of the consequences of their actions. So they can’t drive until a certain age, they can’t drink, they can’t vote. But for some reason, when they commit a crime that we feel is serious enough to move them into an adult court, there’s no protection for children anymore, and so that disconnect is something that I think needs to be addressed.

I think so often when we hear about these cases, we only hear about the crime, the one incident that led to the sentence, but we don’t really understand who these children are or where they come from, what their situation is, how they grew up. — Nadine Pequeneza, producer/director

JJIE: Start to finish, how long did it take to make “15 to Life” and how do you plan to build public awareness about the issues it raises?

Pequeneza: It took three years to make “15 to Life,” and we’re working on an outreach campaign now, so I’ll be working for at least another year making sure that the film gets out to communities where legislatures are reconsidering, rethinking their youth sentencing practices because of the Supreme Court decisions. So we want to use the film to raise public awareness and we’re working with the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth to do that. We hope children who get lengthy sentences have an opportunity for review to see if they have matured, if they have been rehabilitated, and then grant them the possibility of parole if a parole board or judge deems that to be appropriate. We want to add Kenneth’s voice to the discussion so people can get a better understanding of the issue and what needs to be considered and get a sense of who these kids are because so often I think we do a very poor job — the media, actually — a very poor job of representing these children as real people, as more than just someone who committed one terrible act. What the Supreme Court decisions have said — both Graham and Miller — is that those kids have to be given an opportunity for release based on demonstrated maturity and rehabilitation. And so in order to find out if they’ve demonstrated that, they have to have periodic reviews, and so that’s what different state legislatures are enacting now.

JJIE: What surprised you most about Young and his case?

Pequeneza: One of the things that really surprised me is that at the time of his original trials, he had six different public defenders. And he never testified at his trials, and the public defenders that I spoke to who were involved with his case said it was very difficult to build a defense for him because he wasn’t actively helping them build that case. I found out doing my research that this is often the case with children because of their immaturity, their inability to understand consequences and never having been in an adult court system facing such a serious crime. And for most of the kids who get a juvenile-life-without-parole sentence, it’s their first adult conviction. So it’s completely foreign to them, and they’re not equipped to operate in that setting. And so it’s not surprising that for many of them, the defense isn’t always able to present a compelling case.

Kenneth attempted suicide twice while he was going through the original trials, which happened over the span of four years. So [officials] were waiting until all four of his trials were completed and also for him to reach 18 before transferring him into the prison system. He was in solitary confinement for his own protection, but we know based on research that solitary confinement is extremely damaging for a child’s psyche. Kenneth suffered a lot of that, which could have been a contributing factor in his suicide attempts.

I think most surprising to people is that Kenneth’s rehabilitation didn’t really seem to count for much in his resentencing, and people are really surprised by what the judge said at his resentencing. I shared the surprise that a lot of people are voicing in screenings that we have had and on our website and Facebook page. In a case where it’s clearly demonstrated that there has been rehabilitation and given that Kenneth committed these crimes as a child under the influence of an older person and was unlikely to commit these crimes on his own, it seems that he wouldn’t be a public threat.

JJIE: What did you find most fulfilling about making the film?

Pequeneza: One of the reasons I got into documentary filmmaking is I think it’s a wonderful way for people to really experience somebody else’s life, somebody else’s situation and by experiencing that, by living through something with them, they have a better understanding of important social issues — things that we’re all concerned about, but aren’t necessarily as acquainted with as we should be in order to participate in the kinds of reforms that would bring about the changes that we all want. We’d all like to live in safe communities and have reduced youth crime and reduced crime in general. So I don’t think we want different things. It’s a matter of engaging people in an issue and giving them information allowing them to become part of that discussion. So that’s why I make documentary films, and I hope that they’re able to change things for the better.

JJIE: How did Florida law allowing cameras in the courtroom help make the film possible?

Pequeneza: In making documentaries, you’re always looking for a compelling narrative that is pulling viewers in and allowing them to experience the film as it unfolds. This was key to the success of the film. Being able to record that resentencing hearing — everything discussed in the courtroom about the main principles of Graham and Miller, Kenneth’s childhood, upbringing, the influence of Bethea, Kenneth’s record in the Department of Corrections — all this reinforced the narrative, and we were also able to introduce some of the victims of the crimes.

JJIE: How did getting to know Kenneth Young change you as a person, as a filmmaker, as somebody immersed in this topic?

Pequeneza: I’ve been a filmmaker for 15 years and so I’ve met a lot of different people in the course of filmmaking. But what really struck me about Kenneth was his positive attitude. In the main interview in the film, we spoke to him about two hours after he had been resentenced. He was hoping to be released. And the fact that he was so hopeful after receiving a sentence that would keep him in prison for so many more years, I found remarkable. And that’s something that I always will remember about Kenneth. He has incredible resilience and a positive outlook, which I think says a lot about his chances for success upon release.

(PBS provides a wealth of resources – including materials for educators, additional video, letters from Young, background on key U.S. Supreme Court decisions and information on hosting premier parties large and small – at the website “15 to Life: Kenneth’s Story.” Teachers who wish to purchase the film for their classroom or school can contact Outcast Films.)

Financial supporters of JJIE may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.

I am sickened by the judicial system and the judges remarks. To commit a child at 15 years of age to life is not only cruel and unusual punishment it is also inhuman. With that said, I understand that anyone who commits a crime should be punished however; a sentence of life is inconceivable. This seems like genocide to many African Americans.