“I was in prison and you came to visit me.”

— Matthew 25:36

WAYNESBURG, Pa. — The boy loved to walk in the woods.

He savored the gurgle of the creek as the water tumbled over the rocks, the sweet melody of birdsong, the wind rustling the leaves in the trees that soared high overhead.

It seems a faraway place to him now — now that he has grown into a man, a place of dream stuff.

Five years ago, Kenneth Carl Crawford III returned to that woods behind his childhood home in Oklahoma, but only in his mind — the only way he can go back now, perhaps the only way he’ll ever go there again in his time on this Earth.

After a storm, he had been gazing at a thick forest about 100 yards away when he noticed a bunch of leaves had blown over the high electric fences topped by razor wire and landed in the prison yard at the State Correctional Institution-Greene, here in the southwest corner of Pennsylvania.

Crawford picked up one of the leaves. “It had been a long time since I had touched a part of a tree, let alone held a piece of it in my hands,” he would write in his journal.

He kept looking at the leaf, mesmerized, nostalgic for so much of a bit of boyhood paradise lost.

Then he took the leaf back to his 8-by-12-foot cell and decided to recapture some of what he missed so dearly — and ultimately painted on it a scene right out of the woods he remembered.

Then he took the leaf back to his 8-by-12-foot cell and decided to recapture some of what he missed so dearly — and ultimately painted on it a scene right out of the woods he remembered.

He’s been painting wildlife scenes — and painting them superbly — on leaves ever since.

Crawford, 31, has plenty of time to create his miniature masterpieces. He’s serving a mandatory life-without-parole sentence for his involvement in a double murder at age 15 in 1999.

His only hope for an eventual resentencing hearing is the U.S. Supreme Court, which on March 20 agreed to consider a Louisiana case in which it will decide whether to apply retroactively its landmark 2012 Miller v. Alabama ruling, declaring unconstitutional mandatory sentences of juvenile life without parole.

The high court did not clearly specify whether the ruling should apply to cases decided before Miller, and state courts and lower federal courts have been divided. That has left about 2,100 people nationwide imprisoned under sentences of mandatory life without parole for murders they committed as juveniles.

“A window to your soul”

Cindy Sanford will never forget the first time she saw some of Crawford’s paintings.

She was managing an art co-op in 2009 in the small town of Berwick on the Susquehanna River in east-central Pennsylvania when a woodcarver, whose friend had been Crawford’s cellmate, brought in some of the painted leaves.

Sanford, now 56, recalls gasping at their beauty: a newborn fawn, a woodpecker peeking out of a hole in a tree, a wood duck on a log, a white-tailed deer, a cougar looking like it could leap off the leaf.

When she first saw the art, she knew the artist was a prisoner at a maximum-security prison but not that he had been convicted of murder.

At Sanford’s co-op, Handmade Gems and Treasures, she also sold her own wares — glass jewelry she made in a kiln — and appreciated the transcendent power of art.

“I remember really studying the wildlife paintings and thinking, ‘How could anyone evil paint something so beautiful?’” Sanford says. “I felt art was a window to your soul, and I remember thinking that and thinking, ‘No, he couldn’t be evil. Whatever he was, whatever he did, he could not be 100 percent evil creating something like this.’ It was that powerful to me.”

But when she learned a felon serving a life sentence for murder had painted them, she wanted to keep her distance.

“I’ve always been a big believer in law and order, and at that time, I’m not thinking there’s anything redeeming about him,” she says. “For a long while, I was very suspicious of him and didn’t believe anything he said.”

Sanford — a conservative Republican and the wife of a retired Pennsylvania wildlife conservation officer and granddaughter of a New York City police officer once shot in the leg while on duty — firmly believed those guilty of murder should be locked up for life.

But Crawford kept sending his paintings, and Sanford’s co-op kept selling them. Before long, his leaf paintings outsold the works of the co-op’s woodcarver, and Sanford moved the paintings to a more prominent place. The woodcarver, miffed when Sanford refused to use proceeds from the paintings to pay the rent for his space, packed up his ducks and left.

With that, Sanford lost the go-between connecting the co-op to the prisoner. She needed to pay Crawford for works that had sold and wanted to ask him for more paintings. After all, her customers couldn’t seem to get enough of them.

With that, Sanford lost the go-between connecting the co-op to the prisoner. She needed to pay Crawford for works that had sold and wanted to ask him for more paintings. After all, her customers couldn’t seem to get enough of them.

Sanford got Crawford’s address at the prison from her sister, who had bought one of his matte-mounted leaf paintings, which had the prison’s Department of Corrections return address on the back.

When Crawford received the letter, he was doing a 120-day stint in solitary at SCI-Greene — for allegedly having unauthorized art supplies that he says other inmates gave him as they prepared for release and for cutting out wildlife photos from a magazine.

In late 2009, Sanford’s art co-op closed, a victim of the Great Recession, which hit Berwick hard.

And Cindy Sanford, who no longer had a place to sell Crawford’s art, all but forgot about him.

Then she got a Christmas card from him in 2010, followed a few days later by a polite letter in which he addressed her as “ma’am,” and she responded by sending him a Christmas card.

Sanford, in an absorbing new book chronicling her relationship with Crawford, “Letters to a Lifer: The Boy ‘Never to be Released,’” recalls reading part of his letter to her sister on the phone.

Be careful, her sister warned. He could be a serial killer.

Having Googled SCI-Greene, Sanford knew the 2,000-inmate Supermax prison held murderers, gang members, drug dealers and prisoners on death row.

Now, added to her newfound knowledge of the prison, the specter of a possible serial killer did nothing to ease her anxiety. (And Crawford had her return address, prompting more fears: What if he escaped or had connections outside the prison who could do her harm?)

Upbeat letters, sad eyes

Crawford’s letters kept coming.

“Hello, Ma’am,” he wrote in one. “How are you? I hope you are well. I was so happy and surprised to hear from you. You can’t really know how much a simple thing like a Christmas card means to me. For that little show of kindness, I am deeply grateful.”

And he included a few photos of himself, which belied Sanford’s expectations of a bald, tattooed man with missing teeth. Looking at the boyish-faced man with close-cropped brown hair, she focused on the translucent blue eyes that somehow appeared so sad.

When she wrote back to inform the leaf artist that her co-op had closed, he responded by saying he would pray for her and assuring her, “Another opportunity will present itself.”

His ever-polite letters notwithstanding, Sanford decided she had enough going on in her life without taking on the added burden of a pen-pal relationship with, of all people, a convicted murderer.

She was still shaken by the closing of her art co-op when her mother died of cancer just four months after being diagnosed. Two of her three grown sons, David and Jeff, had left for two-year, overseas church missions. In her role as a part-time registered nurse, she had seen way too many people die.

And her husband had warned her that many criminals were scammers.

But Crawford’s letters soon began softening her skepticism.

He told of how he taught himself to paint by studying books from the prison’s modest art room and described the painstaking process to create the artwork using leaves as canvasses. Crawford collected the leaves in the prison yard, soaked them clean in water and left them pressed between the pages of books for months to flatten them. Then he coated them with layers of base paint used as a preservative and, finally, painted the stunning wildlife images onto the leaves.

In another letter a few weeks into 2011, he wrote: “Most inmates get dragged down in the environment that’s created in here. But the Lord has given me many things that I like to share, and has given me my art as the way of sharing it.”

In another letter a few weeks into 2011, he wrote: “Most inmates get dragged down in the environment that’s created in here. But the Lord has given me many things that I like to share, and has given me my art as the way of sharing it.”

Still, Sanford’s anxieties persisted: After all, she thought, this was coming from a convicted murderer.

But by that time, she and her husband, Keith, say today, they believed that perhaps God had put Ken Crawford in their lives for good reasons.

In his journal, Crawford wrote that he’s overjoyed Cindy Sanford continues writing to him even though he no longer has art supplies, and the art room at SCI-Greene had closed because of budget cuts.

“I just want someone to see me for who I am now, and know how thankful I am to God for bringing me a friend,” he wrote in his journal. “I prayed for some relief from all the hard times in here and it seems that Mrs. Sanford might be the answer to that prayer.”

For the Sanfords, a pivotal point in their relationship with Crawford came when he politely declined their offer to give him money for art supplies, saying too many inmates take advantage of people on the outside.

“I think the most powerful thing for us was when he turned down our offer to help him with art supplies,” Cindy Sanford says now. “That was kind of proof to us at that point that this wasn’t just about what he could get out of this.”

Unlikely pen pals

In his early 2011 letters, Crawford offered hints of a Dickensian childhood, as he and siblings suffered severe abuse and neglect at the hands of their parents and various foster parents.

Cindy Sanford empathized to a degree, for she had endured an emotionally distant, alcoholic father who never showed her love or his approval of her.

A few months after Cindy Sanford and Crawford began exchanging letters regularly, he asked if it’d be OK to call her.

She said yes, and during the first call, he thanked her profusely for talking to him. He explained that he hardly heard from anyone on the outside except his grandmother, with whom he spoke only occasionally. (“Grandma Fay” died in March 2013.)

In a letter soon after the call with Cindy Sanford, Crawford asked if the Sanfords might visit him.

She and her husband talked it over and decided to make the nearly five-hour, one-way trip across the state from their home in Mifflinville, Pa., to the prison. They figured they would spend maybe two hours at SCI-Greene, then go shopping in nearby Pittsburgh.

Ken Crawford, DOC Inmate No. EN4939, didn’t sleep the night before the Sanfords’ first visit in the spring of 2011.

He was so nervous about finally meeting them, and desperately wanted to make a good impression.

He did. Indeed, they stayed for the entire six-hour visiting period.

At the end of that first visit, Keith Sanford, 62, recalls Crawford’s saying in his Oklahoma drawl, “Y’all can come back tomorrow if you want.”

Adds Sanford: “You look at that smile and those puppy eyes — and I thought we were going to Pittsburgh.”

They never made it to the city on that trip. They’ve come back to visit Crawford for nearly four years and now visit two days of every month and talk to him on the telephone almost daily.

Murder and remorse

On that first visit, they talked about Crawford’s childhood. About his life in prison. About his artwork. About the July 1999 murders at the Paradise Campground Resort in Nescopeck, Pa., just 15 miles from the Sanfords’ home. Cindy Sanford recalled the murders so close to her home — and the ensuing manhunt — and how she had feared for her sons’ safety.

Crawford, who was 15 at the time of the murders, had been traveling the country with a fellow drifter and carnival worker, 18-year-old David Lee Hanley.

The murder victims — Diana Lynn Algar, 39, and her friend Jose Julian Molina, 33 — had picked up Crawford and Hanley, who were hitchhiking near a truck stop.

The victims had been beaten, robbed and shot. Their bodies were found inside Algar’s trailer.

Fox TV’s “America’s Most Wanted” featured the high-profile case within days of the crime.

About eight months later, Crawford, who had been in a juvenile detention center in Missouri on an assault charge, was extradited to Pennsylvania, and Hanley was arrested in Florida around the same time.

Hanley pleaded guilty to two counts of first-degree murder in August 2000 in a plea bargain to avoid a possible death penalty and is now serving a sentence of life without parole at State Correctional Institution-Smithfield in the Allegheny Mountains in Huntingdon, Pa.

A jury found Crawford guilty in January 2001.

Crawford, who was tried as an adult, testified at his trial that he drove the getaway car but did not kill either victim. A defense witness in the case, who had been Hanley’s cellmate, Paul Grodis, testified that Hanley had admitted killing both victims.

See sidebar "Supreme Court to Weigh Retroactivity of Mandatory JLWOP"

Crawford said he would always regret his role in the murders. “I was too drunk and full of pills and have only myself to blame,” he wrote to the Sanfords.

The victims, he continued, “were good people and their families did not deserve the pain and suffering they endured. I have begged the Lord for forgiveness and I believe I have been forgiven. But I will never forgive myself.”

After reading the letter, Cindy Sanford says now, she believed Crawford was genuinely repentant.

Whether Crawford is repentant remains immaterial to Robert Algar Jr., the widower of murder victim Diana Lynn Algar. He says her killers do not deserve sympathy and should never be released from prison.

“They’re in jail. They’re not in there to be protected from society; they’re in jail to be protected from me,” said Algar, a transportation dispatcher who lives in Scranton, Pa. “They get out, I take care of them. That’s how I feel about it, really.”

Cindy Sanford says she wrote a letter to Algar but he did not respond.

“My heart goes out to him,” she says. “The loss of his wife is not something that anyone can ever expect him to get over. He’ll never get over that.”

‘I got a family now’

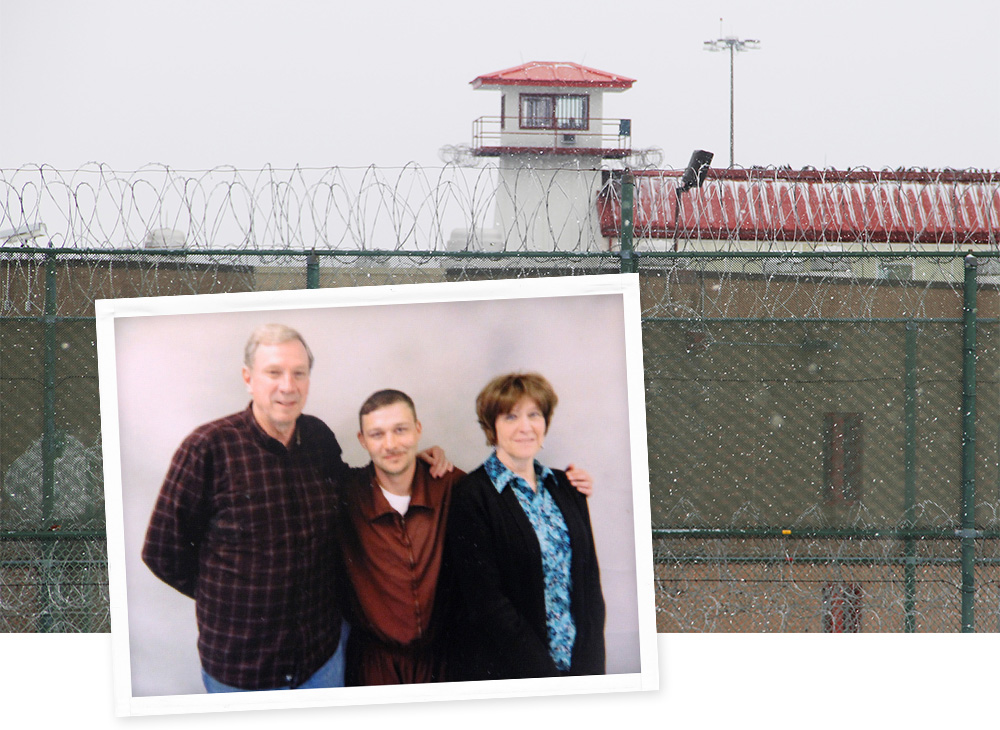

On a frigid, gray Friday in February, a watchtower with an armed guard inside looms large over the sprawling prison complex that is SCI-Greene.

When they enter the prison’s lobby, the Sanfords have the drill down. They leave their wallets in a locker, take off their belts to go through a metal detector, present photo IDs and have their hands checked by a wand that can detect illicit drugs.

They go through heavy steel doors and enter the visiting room, which resembles a large waiting room in a hospital, only more drab, with a watchful corrections officer sitting at a raised platform desk.

Crawford, a big smile on his face, rushes up to hug them. He greets them this way every time.

“It definitely feels like I got a family now,” says Crawford, wearing a burgundy jumpsuit with “DOC” in big white letters on the back. “It’s better than any family I had.

“It was getting to a point where I needed some help, and these two old-timers came into my life,” Crawford says, and all three laugh — which they do easily and often during the visit.

(Once, before SCI-Greene banned the sale of art inside the prison, Crawford’s paintings had been displayed in the visiting room, but now the light blue walls are bereft of the natural beauty of his art.)

The Sanford couple’s three grown sons — Eric, 31, David, 29, and Jeff, 24 — sometimes visit Crawford too, and all the family members have made Christmas Eve visits.

Crawford, a lean man with the beginnings of a mustache and beard, calls the Sanfords “Mudder” and “Peepaw.”

“I’ve had ‘mothers’ and ‘fathers,’ and none of them turned out too well,” he says.

Indeed, his alcoholic father beat him, his brother and his two sisters with extension cords and switches in drunken rages and often left them home alone in their ramshackle trailer with no electricity or heat and little food. And he forced them to tend to his marijuana plants behind the trailer.

Crawford’s mother ran off with one of her boyfriends to work the carnival circuit when Ken was 5.

Sanford recently tracked down Crawford’s mother through Facebook and asked her to get in touch with her son or at least write him a Christmas card. The mother did neither.

When he was 9, Child Welfare Services came to remove Ken and his siblings from their father’s custody — and promised the children their lives would be much better with foster parents.

They weren’t.

Crawford recalls one 400-pound foster father who forced the children to scratch and bathe his legs because he could not reach down to them.

Another foster father showed off Ken’s ability to play football — until he outshone the man’s biological son, at which point the foster father made Ken quit the team.

A third foster father told him he’d be in prison by the time he was 18.

When Ken was 10 and wetting the bed, his foster mother screamed at him and ordered him to strip naked and lie on a towel on the living room floor. As other children in the home laughed, she put a diaper on him and made him wear it to school the next day.

He wet the bed again that night, and she forced him to sleep in the bathtub.

If he could change two things in his life, Crawford says now, he would have never have hung out with David Lee Hanley, and, if it were somehow possible, he would have eluded Child Welfare Services workers.

“If I could go back in time, I would have hid from Child Welfare Services. I should have hid. I shouldn’t have let them find us,” he says.

Speaking of his father’s abuse and neglect, he says: “That’s what we knew. It was nothing out of the ordinary for us. We still had something, and the physical abuse we grew up with I was used to.

“In foster care, it was mental abuse, and the mental abuse was much worse.”

Still, he’s quick to add that he doesn’t blame anybody for the circumstances that led to the double homicides. “I made the choices,” he says.

Crawford ran away from his last foster home as a 12-year-old, lied about his age and became a nomadic carnival worker who stayed in hotels or trailers in Pennsylvania, New York state, Massachusetts, Arkansas, Texas, Louisiana and Kentucky.

He began smoking pot daily and by age 14 became addicted to painkillers he was prescribed after putting his arm through a window while chasing a man he saw slap a young boy in Henderson, Ky.

But Crawford tries not to dwell on the past and has a knack for lifting the spirits of others — even in a place plagued by gangs, violence, drugs, racism – and a suicide that shook him badly. The victim had been dragged out feet-first in a body bag while some prisoners and paramedics laughed.

Crawford found nothing humorous about it.

Before the inmate’s suicide, Crawford had befriended another despondent inmate — his former cellmate, or “cellie,” nicknamed “Tivo,” a lonely soul who never received mail and did not believe anyone loved him.

At the time, Crawford and Tivo were the only black and white inmates in the same cell in the entire prison.

Crawford, whose nickname at the prison is “Oak” (short for Oklahoma) decided on his therapy: Every day, he would give Tivo a hug and say, “I love you.”

Pretty soon, Tivo came to believe it and no longer felt so alone.

Crawford also noticed a mentally challenged inmate, Randy, kept getting in trouble for breaking rules after other inmates told him to do so. Then Crawford befriended Randy and persuaded other inmates to back off.

Once during a football game in the prison yard, Crawford talked the coach into putting Randy into the game for a change, and then got other inmates to purposely let Randy gain a lot of yardage on a handoff.

Crawford says he leavens the mood and relishes keeping other inmates entertained, which in turn improves his outlook.

Sometimes, that means being enterprising — like when he created a miniature golf course in his cell by making clubs from rolled-up paper and cardboard, balls from deodorant and holes from empty cups and toilet paper rolls.

He’s a model prisoner, the guards tell the Sanfords, and maybe that’s why they allow violations of the rules on “contraband.”

Every spring, Crawford “adopts” a baby bird that falls out or is kicked out of nests in eaves next to the prison yard, names it, feeds and cares for it in his cell, then frees it into the wild, recalling the Birdman of Alcatraz, Robert Stroud.

And while Crawford has only a sixth-grade education, he earned his GED and now takes correspondence courses through Hobe Sound Bible College, a well-established school that opened in 1960 in Southeast Florida. Cindy Sanford agreed to pay half the tuition as long as Crawford got no grades lower than a B. He has made straight A’s thus far.

He’s an avid reader whose favorites include the Bible, art books, fiction and his college textbooks, and he relishes beating the Sanfords at Bananagrams, an anagram word game played with Scrabble tiles.

Cindy Sanford marvels at his progress, and says it clearly demonstrates he no longer resembles the boy convicted half a lifetime ago.

But with all the misgivings, the heartbreak, the tears, the tantalizing but unrequited dream that Crawford will one day be freed and the Sanfords will be able to take him into their home (as they did with a homeless man from 2007 to 2009), what keeps the Sanfords from losing hope?

“Just plain old love right now, and it’s not like this is some divine mission I think I’m fulfilling or anything like that, which is not to say that I don’t think God has had a hand in it,” Cindy Sanford says. “It’s love. That’s my son. I would never think of letting him go, never.”

She and her husband have closely followed rulings relating to Miller retroactivity. They went to the U.S. Supreme Court in Washington for the oral arguments in Miller v. Alabama and had their hopes dashed when the Pennsylvania Supreme Court ruled 4-3 in October 2013 against applying Miller retroactively to the state’s estimated 500 juvenile lifers.

But they cling to their dream that the U.S. Supreme Court will rule Miller retroactive — and that Ken Crawford may one day be freed.

So does Crawford’s lawyer, Sara Jacobson.

“I think with Miller, the court was essentially recognizing that people are worth more than the worst moment in their life and certainly that kids can be reformed,” says Jacobson, a professor at Temple University Law School in Philadelphia. “It’s just a tragedy that so many people who have been sentenced to life without parole as juveniles don’t have the opportunity for courts to even look at their cases, to look to see whether they’ve been reformed."

For now, Crawford keeps painting wildlife scenes, now being sold at The Gold Leaf Frame Shoppe gallery in Williamsport, Pa. (His works have fetched up to $375.)

And Cindy Sanford longs for a day he’ll be able to walk once more in woods far beyond the high walls of the prison.

She says she has forgiven Crawford and knows God has forgiven him too, no less than the Lord forgave St. Paul for persecuting Christians before his conversion.

“I believe in a God who forgives us, if you approach him and you’re remorseful,” she says. “God loves us all. There’s no saints on this Earth. I believe God loves him as much as he loves me.”

As 3 p.m. approaches, the end of visiting hours, Ken Crawford’s smile fades, and his eyes turn downcast. He tells Mudder and Peepaw he loves them.

The three of them embrace before Crawford heads back to his cell block.

And the Sanfords are already looking forward to the next month’s visit with the man they now consider a fourth son.

See sidebar "Supreme Court to Weigh Retroactivity of Mandatory JLWOP"

This article also featured in the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

This is such a heart wrenching article. It is impossible not to want this young person’s release from incarceration. Yet, there are other juveniles tried as adults and imprisoned for life without the possibility of parole who are not perhaps as redeemed, not perhaps as artistically talented, not perhaps as befriended – inside or outside of prison. These juveniles also deserve our outrage at how the society has failed them. Children make mistakes. These mistakes can be horribly damaging to themselves and others. But our failure has been to simply continue the torture that characterized their young lives; to exploit their mistakes for political profit and victim revenge. What we are doing is not the mark of a civilized society. We must demand an end to the oxymoronic notion that children can be tried as adults.