NEW YORK — Life prospects appeared bleak for 17-year-old Terrance Williams on a quiet Saturday in the spring of 2013.

He was facing years in prison on charges of armed burglary. This was just the latest setback in a rough and tumble Philadelphia childhood that had taught him that the only way to make a living was by hustle and crime.

Then Terrance noticed a bit of ruckus coming down the hallway of the Philadelphia jailhouse where he awaited his day in court. Someone was shouting that people should get a move on. Terrance turned to his cellmate and asked what was going down with something called “YAS.”

“They play Gotti [the rapper], bro,” his cellmate said. “I just go there for the music.”

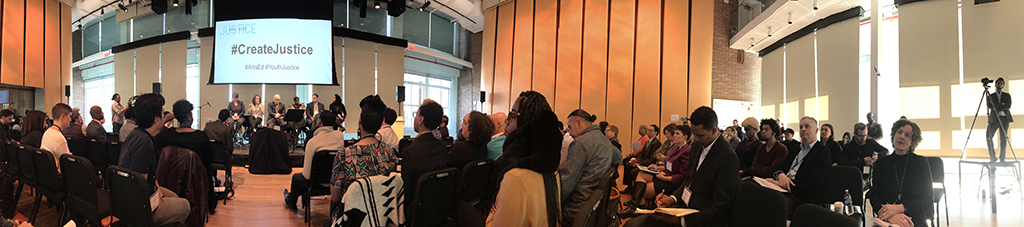

More than 100 artists, activists and public officials gathered at Carnegie Hall March 23-24 for a forum promoting cooperation among juvenile diversion programs.

But activists with the Youth Art and Self-Empowerment Project (YAS) had something to say to the assembled juveniles: There was a way out of prison but in order to make it, Terrance and all the others had to try out some rap and rhyme of their own.

For more information about EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES, go to JJIE Resource Hub | EVIDENCE-BASED PRACTICES

More than 100 artists, activists and government officials gathered in New York City on Thursday for the first of two days to discuss how groups like YAS can take their outreach to a higher level. The event was the first of two forums organized by Create Justice, a partnership between Carnegie Hall and the Los Angeles-based Arts for Incarcerated Youth that aims to catalyze partnerships among ongoing juvenile justice initiatives.

Some of the groups represented teach juvenile offenders how to write songs. Others put youth to work on public art projects. Some bring judges, prosecutors and youth together for days of fun and mutual understanding. Others reach out to parents to make sure that they do their part to keep youth in schools and out of prison. They will all come together one year from now to demonstrate the results of their collaboration in a March 2018 concert at America’s premiere concert hall.

Ana Bermudez

Art diversion programs demonstrate that there are better ways to treat juvenile offenders, especially considering the fiscal and societal costs of locking them up, said Ana Bermudez, New York City commissioner for the Department of Probation.

“Give me the $200,000 it takes to incarcerate a juvenile and I’ll show you shit to do,” she told the crowd. “It’s almost that easy.”

Juvenile incarceration rates rose in the 1980s and 1990s when the war on drugs led to harsher sentencing laws across the county. A national drop in crime and new research into brain development has led to a new appraisal of the wisdom of locking up juveniles.

For youth like Terrance Williams, an opportunity to make some art was all it took to change his ways.

A drug-addicted mother and a recidivist father meant that Terrance was on his own at a young age, learning that the only thing that pays is a crime you’re not caught at. But people said they wanted to keep him and others out of prison at that first YAS meeting that he attended, he said. Once he gave poetry a chance, the other lessons the activists brought began to sink in.

“I was just writing so freely about everything that was on my mind, whether I was going upstate, that I regretted doing what I did, that when I get out I’m was going to do what I had to do to get right,” he said.

“I was just writing so freely about everything that was on my mind, whether I was going upstate, that I regretted doing what I did, that when I get out I’m was going to do what I had to do to get right,” he said.

Activists vouched for him in court, and his worst fear — serving time with hardened criminals in an adult prison — did not come to pass. He took a plea deal and was released on probation. But the old problem of how to make a living returned.

This time he did not grab a .357 revolver and break into a neighbor’s house. He tried applying for a job at Wal-Mart but his felony record disqualified him. Employment prospects were still bleak until another opportunity presented itself — a part-time job with YAS teaching juvenile offenders that they too could make a literary escape from prison.

Four years after that fateful day in a Philadelphia jail, he was representing YAS at Carnegie Hall with a new purpose.

“I’m a leader,” he said. “I’m trying to make a change that benefits all my peers.”

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.