The bad news: recent research indicates that schools suspend far more kids than they need to, and youth – especially youth of color, though not always -- suffer unfairly for it.

The bad news: recent research indicates that schools suspend far more kids than they need to, and youth – especially youth of color, though not always -- suffer unfairly for it.

The good news? Sure, zero-tolerance school discipline policies need revision. But there's another solution to the problem: changing school culture by implementing mediation and "restorative justice" techniques in schools.

First, the background. "Suspended Education: Urban Middle Schools in Crisis," by Daniel J. Losen and Russell J. Skiba, published by the Southern Poverty Law Center, makes for fascinating and depressing reading. After reviewing more than 30 years of data from nearly 10,000 middle schools nationwide, it concludes that suspension is over-used as a disciplinary tool, and that youth of color -- black males especially -- are suspended far out of proportion to their numbers.

The authors looked specifically at types of suspensions where school staff could exercise discretion -- incidents of fighting, disruptive behavior and so on. They analyzed how many youth were suspended and broke down differences by race/ethnicity, and gender.

The authors looked specifically at types of suspensions where school staff could exercise discretion -- incidents of fighting, disruptive behavior and so on. They analyzed how many youth were suspended and broke down differences by race/ethnicity, and gender.

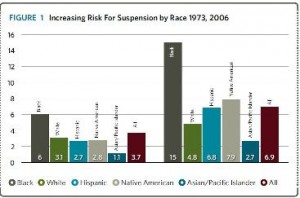

What they learned was appalling: suspension rates have nearly doubled for students of all races/ethnicities since 1973; African American, Latino, and American Indian youth were suspended at higher rates than white youth; 6 percent of all black students were suspended in 1973, compared with 15 percent in 2006; and a breathtaking 28.3 percent of black males were suspended in 2006, compared with 10 percent of white males.

When researchers looked at the 18 largest urban school districts, they found that most "had several schools that suspended more than 50 percent of a given racial/gender group." They even found schools that suspended more than half of their white and Hispanic female students.

Seriously. 50 percent.

Worse, the authors point out that the federal data they used only counts students who've been suspended at least once -- it doesn't actually count the number of suspensions. So their conclusions probably underestimate the frequency of suspensions, and the impact on these students' classroom time (which is linked to their likelihood of dropping out and, of course, their chances of ending up in the juvenile justice system).

You might be shrugging your shoulders and saying, "Well, if it makes the school safer and helps other students learn better ..." Here's what the authors have to say about that:

[D]espite nearly two decades of implementation of zero tolerance disciplinary policies and their application to mundane and non-violent misbehavior, there is no evidence that frequent reliance on removing misbehaving students improves school safety or student behavior.

In fact, frequent use of suspension and expulsion as disciplinary tools doesn't seem to help other students do better:

[E]merging data indicate that schools with higher rates of school suspension and expulsion have poorer outcomes on standardized achievement tests, regardless of the economic level or demographics of their students. It is difficult to argue that disciplinary removals result in improvements to the school learning climate when schools with higher suspension and expulsion rates average lower test scores than do schools with lower suspension and expulsion rates.

Since research suggests that instructional time is strongly related to achievement outcomes, a policy shift is necessary:

It is critical to note that schools with very high suspension rates (e.g., suspending one-third or more of the student body at least once) are not receiving the kind of public attention or regular exposure that schools with low test scores receive.

The disparate impact on youth of color, and black youth in particular, makes this a civil rights issue, the authors say. Here's why:

Research on student behavior, race, and discipline has found no evidence that African-American over-representation in school suspension is due to higher rates of misbehavior (McCarthy and Hoge, 1987; McFadden et al., 1992; Shaw & Braden, 1990; Wu et al., 1982). Skiba et al. (2002) reviewed racial and gender disparities in school punishments in an urban setting, and found that white students were referred to the office significantly more frequently for offenses that appear more capable of objective documentation (e.g., smoking, vandalism, leaving without permission and obscene language). African-American students, however, were referred more often for disrespect, excessive noise, threat, and loitering -- behaviors that would seem to require more subjective judgment on the part of the referring agent. In short, there is no evidence that racial disparities in school discipline can be explained through higher rates of disruption among African-American students.

What can be done?

One solution: mediation. And here's evidence from two Connecticut schools that mediation lowers suspension and expulsion rates.

For stronger evidence, check out this international report, "Improving School Climate: Findings from Schools Implementing Restorative Justice," showing that restorative justice and mediation in the schools has a significant positive impact on student behavior. (Restorative justice focuses on repairing the harm done to the victim, and is usually accomplished in a cooperative process with all relevant stakeholders.)

When these techniques were implemented in 10 schools in the U.S. and Canada, large drops occurred in suspensions and "behavioral incidents." Results varied by school, but reviewing the data and the comments from school teachers and administrators is inspiring.

Given the data uncovered by the Southern Poverty Law Center, it's obvious that school administrators are reaching for the suspension hammer too often. In most cases, it's safe to assume that they probably didn't feel that they had another option.

Now, they do. It's time to start using them.

The above story is reprinted with permission from Reclaiming Futures, a national initiative working to improve alcohol and drug treatment outcomes for youth in the juvenile justice system.