This story is from the The Crime Report

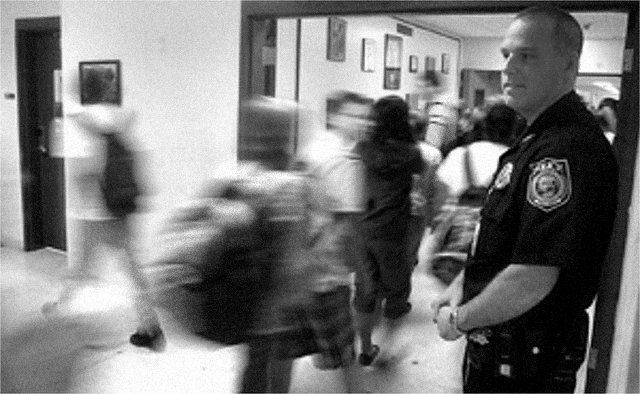

Arkdog / Flikr

Police Officer and Cortland City School Resource Officer, Rob Reyngoudt. Cortland, New York.

The debate over placing more armed guards in schools has turned the spotlight on school resource officers (SROs), who comprise an increasing share of law enforcement personnel in schools—and who worry that their role is misunderstood.

A point of view largely missing from the discussion is whether someone who is sworn to protect school safety should be armed, says Mo Canady, executive director of the National Association of School Resource Officers (NASRO).

“When I first got started in this, I was a little concerned that kids were going to be focused on my gun,” added Canady, a former police lieutenant who spent 12 of his 25 years as a school safety officer in Hoover, Ala., where he still lives, and where the national association is based.

“But they weren’t,” he continued. “As I interacted with them and got to know them, it humanized my role. And, yes, I do realize that they still were seeing me as law enforcement.”

Last month, the National Rifle Association (NRA) triggered a heated back-and-forth about the role of guns in schools when it urged 40 to 60 hours of firearm training for teachers and other school staff who want to carry guns.

The NRA’s National School Shield report recommended, for example, a "model training program" that also would include a background check for school staffers seeking gun permits.

Such training would add an "important layer of security for prevention and response in case of an active threat on a school campus," the report said, claiming the training was especially critical for cash-strapped schools that cannot afford other types of security personnel.

So far, South Dakota is the only state that permits teachers to carry guns in schools, but several other states have been considering similar legislation.

$150 Million for School Security

For his part, President Barack Obama has proposed allotting $150 million nationwide for more SROs in schools that opt to employ them, and for more school psychologists and counselors to address the needs of students with behavioral problems.

NASRO’s Canady told The Crime Report that those who oppose the presence of armed officers fail to take into account classroom realities.

According to the latest available data from the National Center for Education Statistics, 85 percent of public schools reported one or more acts of assault, theft, rape or other offenses in the 2009-2010 school year.

That amounted to 1.8 million crimes in that period, or 40 for every 1,000 students. At the same time, 60 percent of the nation’s schools sought police intervention in handling 689,000 crimes, or 15 for every 1,000 students.

The same report also noted that the number of 12- to 18-year-old public school students reporting they were crime victims at school dropped from 7.6 percent in 1999 to 3.9 percent in 2009.

Of 33 deaths of students, non-students and staff in schools, the center reports, 25 were homicides, five were suicides and three resulted from police action that was deemed legal.

Against that backdrop, says Canady, SROs should be considered dedicated professionals who play a key role in protecting young people and often expressly choose to be assigned to the schoolhouse beat.

Nevertheless, he added, in some school districts around the country, SROs’ collaboration with educators, school counselors and law enforcement still leaves much to be desired.

“There has to be inter-agency collaboration between law enforcement and a school district,” he said. “There has to be a written plan and agreement. It has to be the right officer and it has to be the right fit.”

Yet, many critics “are lumping all the armed guards, armed security, school safety officers—trained or not—into one big barrel,” he added.

Less Than Half of US Schools Employ SROs

SROs, however, are a specific class of professionals and usually wear their departmental uniforms while at school. According to the National Center on Education Statistics, 42.8 percent of schools had SROs during the 2009-2010 school year.

That compares to 46.3 percent in 2007-2008 and 41.7 percent in 2005-2006. Shortfalls in funding for SRO salaries caused that decline, Canady says.

The 2011 report also showed that 28 percent of all SROs, armed guards or other security personnel routinely carried guns while in school during 2009-2010, down from 34 percent in 2007-2008.

Canady, along with Moses Robinson, a 28-year veteran of the Rochester (NY) Police Department, helped facilitate a webinar earlier this month sponsored by the Supportive School Discipline Communities of Practice on “navigating the roles and responsibilities” of SROs.

Robinson, who has spent the last 18 years as an SRO at Rochester’s East High School, says that some critics unfairly dismiss police, as well as armed guards who are not sworn law enforcement officials, as inherently bad for schools and school kids.

“Some people are being totally reactionary in their thinking about intervention and prevention strategies,” Robinson said. “We all need to come to the table and talk about what this really needs to be, to create a plan that is reality-based and not reactionary.”

Robinson and Canady concede that police departments sometimes use their school resource division as a dumping ground for disgruntled officers who weren’t performing well in positions to which they were previously assigned.

But both men argue that the most severe behavioral problems confronted by rural and urban schools—physical violence, drug abuse, gang influences—demand a school resource officer’s presence.

Murdered Students

Since Robinson, who grew up in north Philadelphia in one of that city’s toughest neighborhoods, began working in Rochester’s East High, 15 of its students have been murdered, 14 of them with guns. The other youth was stabbed to death.

Although those killings occurred in the surrounding neighborhood, not on school property, they suggest much about the pressures and temptations confronting youth in that community.

While most students at East are good kids, a small fraction of them are clearly adrift and at-risk for causing major classroom disruptions, Robinson says.

“The goal at the end of the day is not to take anyone to jail,” Canady said.

“It’s to mediate the situation.”

And, Canady says, “When SROs are doing the job right, and they go into the school environment, the arrest rate doesn’t go up, it goes down.”

“If it’s done right,” he said, “It’s the epitome of community-based policing. Done wrong, it’s a nightmare.”

Neither the police officer nor the school are best served when SROs aren’t performing their jobs well, he explained—particularly when arrests are used to discipline disruptive students.

The disproportionate suspensions and arrests of mainly black, brown and disabled youth—exemplified by a March 2013 consent decree banning that practice in Meridian, MS—have raised critics’ ire.

School to Prison Pipeline

Education reform advocates cite research demonstrating, they say, that suspensions from classroom heighten the chances that suspended students will flunk, drop out, or wind up in the juvenile justice system.

The critics argue instead for more school-based social workers, psychologists and others trained to work with troubled kids.

“Just adding more police is not a good idea,” said classroom teacher-turned-attorney Daniel Losen, director of the University of California at Los Angeles (UCLA) Center for Civil Rights Remedies.

“But if we’re going to have school resource officers, that training piece is important. A lot of school districts have police (officers) in schools who are not well trained, and they don’t really have the money to train them. Where will that money come from?”

In January 2013, the UCLA center released Out of School & Off-Track: The Overuse of Suspensions in American Middle and High School, a 2009-2010 school year survey of 26,000 schools, which concluded that one in nine students was suspended.

Most suspensions arose out of minor infractions such as disrupting the classroom, tardiness and violating the dress code. The report did not probe expulsions for more severe criminal offenses.

Because school safety officers can be expected to intervene in all those kinds of cases, the NASRO’s training courses include basic instruction for those newly assigned to schools.

The instructions cover interviewing students; identifying deceptive verbal and written communication from unruly students; and steps to take when a threat requires a school lock-down.

Legal Protections

But the instructions also advise SROs to be conscious of not violating students’ legal protections against unwarranted search and seizure, sexual harassment and other unwarranted or inappropriate intrusions.

With the Tactical Defense Institute, a West Union, Ohio, organization training civilians and law enforcement and military personnel, NASRO offers the recently created “active shooter response” course, a three-day program that trains officers on how to respond to school shootings.

In addition to intervening and mediating with students, the best SROs also act as informal counselors and teachers, Canady says.

“We train officers on issues such as classroom management, how to take a law-related education topic into the classroom and how to teach kids about the laws of their state or constitutional law,” Canady said.

The courses, he added, are designed to draw the best out of a workforce, and were launched in the 1950s in Flint, Mich., but has surged since former President Bill Clinton introduced the Safe Schools/Healthy Students Initiative in 1999.

The initiative has provided more than $2.1 billion in grants to over 300 local education agencies across the country for anti-violence and drug abuse programs for students.

Both Robinson and Canady make clear that good training remains essential to ensuring that schools are safe from violence.

“You cannot put in place anyone who hasn’t been sufficiently trained to deal with students and expect a positive outcome,” Robinson says.

http://www.thecrimereport.org/news/inside-criminal-justice/2013-05-can-more-armed-guards-keep-our-schools-safe

Freelance journalist Katti Gray covers criminal justice, health, higher education and other topics for a range of national and regional magazines, newspapers and online news sites. A contributing editor of The Crime Report, she welcomes comments from readers.