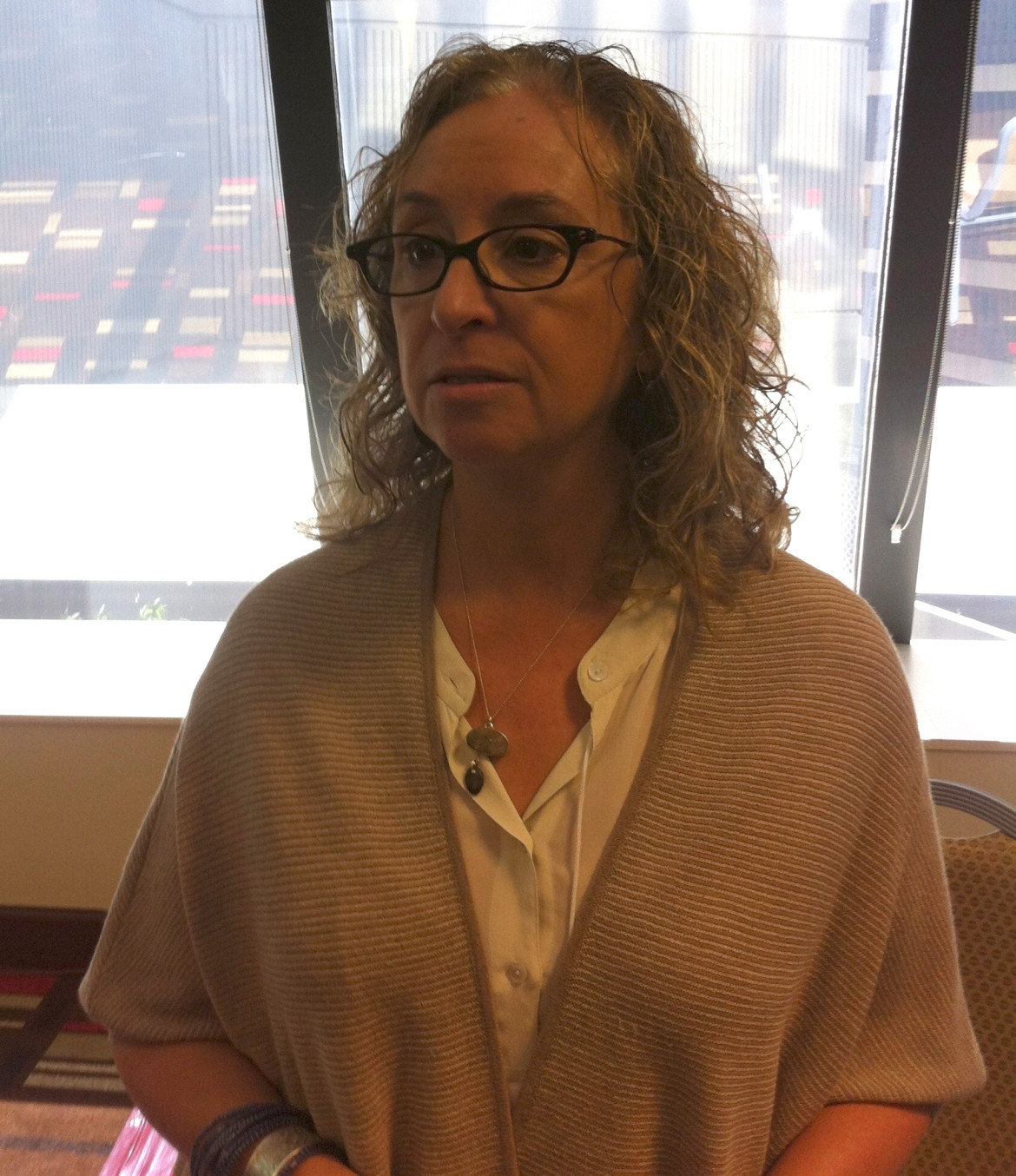

Maggie Lee / JJIE

Francine Sherman; "There’s always some discussion of what fits” the definition of child sexual exploitation, said Francine Sherman, a professor at Boston College Law School and a defense attorney.

ATLANTA -- During the men’s NCAA Final Four basketball tournament weekend in early April here, the FBI arrested four people on child sex exploitation charges and rescued seven minor females. The sex trade is always more active during large events, as is its sinister little sister, child sex trafficking. But for those minors trapped in the sex trade, where they’re found in the United States has a lot to do with how they will be treated by the law.

In part, that’s because “there’s always some discussion of what fits” the definition of child sexual exploitation, said Francine Sherman, a professor at Boston College Law School and a defense attorney. She was leading an April 18 workshop on the topic at the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s 3-day Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative conference in Atlanta.

There is broad legal agreement that pimping out a minor is criminal sexual exploitation of children. But it gets blurrier, especially if only two parties are involved.

“A 15-year-old girl is on the run. She needs a place to sleep so goes home with a 25-year-old young man she meets on the street and has sex with. How many would consider that commercial sexual exploitation of children?” Sherman asked a few dozen judges, attorneys, law enforcement and nonprofit staff from all over the nation at her workshop.

Some said yes, saying the sex was exchanged for lodging, a thing of value. Others said no, saying it wasn’t commercial, or it did not involve cash. Others said coercion would make a difference. They were drawing on their own state rules.

Federal law broadly defines trafficking as engaging in activities such as harboring and transporting persons under the age of 18 for the purposes of enabling commercial sex acts. But state laws about the under-18s vary.

In Georgia, for example, a teen girl or boy can be charged with criminal prostitution. That’s in a state where the legal age of consent for sex is 16.

The law is similar in Texas, though it’s not possible to charge a child under 14 with prostitution since they are too young to consent to sex, said the state Supreme Court in its 2010 ruling In the Matter of B.W.

That same mismatch is the norm in all but a handful of states. “You could prosecute the john for statutory rape and prosecute her for prostitution. It doesn’t make sense,” said Sherman.

It’s very difficult to estimate the number of domestically trafficked children in part because jurisdictions do not agree on what constitutes an exploited child.

Dennis Morrow, executive director of Janus Youth Programs in Multnomah County, Oregon, the Portland area, cited statistics saying about 100,000 children are being trafficked at any one time.

Janus works by the definition that “if a child, girl or boy, is under 18, that’s exploitation, they are a victim,” he said.

But if the laws don’t agree with Morrow’s definition, neither do all the girls and boys that his Janus shelters see.

Some girls try to run away from shelter back to their pimps, Morrow said.

Sherman said some of her young clients say they made the choice to offer sex and are not victims.

When exploited youth come into the legal system, the laws vary and so does the energy and philosophy put into resolving child prostitution cases.

Maggie Lee / JJIE

Police often use what are called masking charges, like trespass, running away from home or technical violations of probation, to keep an exploited child physically secure in jail, Sherman and Morrow both said, a process that’s not written down.

Suffolk County, Massachusetts, which includes Boston, uses a memorandum of understanding among law enforcement and a range of public and private agencies to protect and support youth who are exploited through prostitution.

“Folks came willingly to the table,” said Mia Alvarado, executive director of Roxbury Youthworks. But “discussions weren’t as easy over the years.”

They agreed on key principles, “that this is a form of child abuse,” said Alvarado, though they still wrangle over questions like who is a fit child caretaker.

“I think that what you have is agreements and understandings on the part of law enforcement not to charge (youth with prostitution),” Sherman said, but in most places, the option of a charge is still there.