A few months, and many applications, out of college, when Destin Cretton landed his first job as staff at a group home for troubled teens, he was happy to have a job at all, let alone one where he felt he could make a difference. It wasn’t until some time later, when he was sitting in the cool-down room with one of the clients having an intimate conversation--shortly after the client had punched him in the nose--that he realized how much these teens had dealt with.

A few months, and many applications, out of college, when Destin Cretton landed his first job as staff at a group home for troubled teens, he was happy to have a job at all, let alone one where he felt he could make a difference. It wasn’t until some time later, when he was sitting in the cool-down room with one of the clients having an intimate conversation--shortly after the client had punched him in the nose--that he realized how much these teens had dealt with.

“I was pretty naïve, and I think I went into that place with a little bit of an unhealthy savior attitude, thinking that I could help these kids, could be a light or whatever you want to call it,” Cretton said. “But I quickly realized how complicated things are there.”

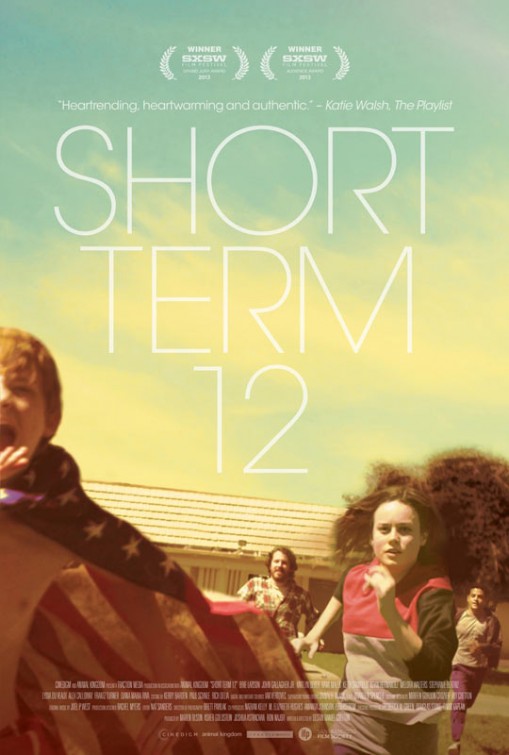

Cretton is the writer and director of “Short Term 12,” a new film that tells the story of the residents and staff of a group home for teenagers who, because of behavior problems that often stem from trauma, abuse or neglect in their home lives, can’t live with their families.

The story weaves through the lives of a handful of residents such as Jayden (played by Kaitlyn Dever), who has recently lost her mother, giving us insight into the complexities faced by children who are funneled into this system. At the same time, the film explores the lives of Grace (Brie Larson), her boyfriend and coworker Mason (John Gallagher Jr.), and Nate (Rami Malek), the newest staff member.

“It’s not just about tragedy,” Cretton said. “It’s about real human relationships that are beautiful and fun and hilarious and inspiring, but also not shying away from the harsh realities.”

Cretton used his own experiences as inspiration, and the time he was punched in the nose was the basis for a telling scene in the film.

When Jayden first arrives at Short Term 12, the group home facility that serves as the setting of the eponymous film, she is a Hollywood cliché: a sullen teenager with a bad attitude and thick, dark eyeliner. But before long, as she sits, waiting for her father to pick her up for a home visit on her birthday, it becomes clear she’s a more fully developed chracter, not just your average angst-ridden teen with a penchant for rock music and cigarettes, but someone who has survived abuse and trauma. Someone who not so much conflicted as she is emotionally choked.

When Jayden first arrives at Short Term 12, the group home facility that serves as the setting of the eponymous film, she is a Hollywood cliché: a sullen teenager with a bad attitude and thick, dark eyeliner. But before long, as she sits, waiting for her father to pick her up for a home visit on her birthday, it becomes clear she’s a more fully developed chracter, not just your average angst-ridden teen with a penchant for rock music and cigarettes, but someone who has survived abuse and trauma. Someone who not so much conflicted as she is emotionally choked.

The tension in the front room builds and the staff exchange short glances, shaking their heads to signify that her father is still missing, while the other residents are a quieter and more rigid than normal. Blood wells from the fresh wound on the back of Jayden’s hand, where she repeatedly uses her thumbnail to dig into her flesh. Then something snaps and she runs down the hall, slamming the door to her room, which is forbidden because of her history of cutting herself.

The staff finally manage to break into her room, but Jayden smashes a birthday cupcake into the face of Grace, the head of the floor staff, before they are able to restrain Jayden. Nevertheless, Grace and the two other staff are calm and comforting rather than angry or punishing, and later Grace lets a bit of her own troubled past show through as she empathizes with Jayden.

“It’s impossible to worry about anything else when there’s blood coming out of you,” she says.

The storyline is fictional, culled from reading and interviews with social workers, psychologists and staff members, as well as from his own experience in the two years he held this job. At the end of those two years, Cretton went to film school, where he directed a version of the film as a short for his thesis, which won the Jury Prize in Short Filmmaking at Sundance in 2009. Nate, the well-intentioned, nervous young man who announces he’s always wanted to work with “underprivileged” children (which isn’t well received) is the character Cretton says he most closely resembled during his time working at the group home.

“I learned pretty quickly that my experience there was a two-way street,” he said. “I learned more from those kids than they learned from me.”

For all the dark plot twists and poignant scenes, Cretton feeds his audience just enough humor to give levity to a serious and often emotional topic, without making jokes at the expense of his characters.

And this was intentional. While he knows the statistics aren’t good—some studies say about 30 percent of the nation’s homeless have been in foster care, and only slightly over half have a high school diploma—he still wanted to portray some of the good moments, too.

“None of us wanted this movie to feel like something that was a chore to get through, we wanted to give people a taste of what it feels like to be in a place like this without torturing them,” he said. “To show some of that on screen would kind of do the opposite of what we hoped for. “

There’s a sense throughout the film that Cretton knows this population and that he has taken the time to thoroughly develop his characters. From the beginning, we can see that Grace is good at her job. She is easy with the clients—strict, but natural, a mentor more than a parent.

But outside of the gates, she’s almost resembles a teenager herself. Her hair falls moodily over one eye and in her relationship with her boyfriend Mason she meets any complexities with silence, refusing his pleas to heed the very advice she dolls out to her clients.

Cretton can identify with this complexity. At 22, he was only a few years older than some of the residents, and had to enforce rules, such as not swearing, which he didn’t follow himself when he left the house. Although he didn’t have a history with the foster care system or abuse, he knew fellow staff members who did. He feels all the staff could benefit from therapy, because of the emotional burden they take on in jobs like these.

And for the residents, Cretton says there is a long way to go. He doesn’t claim to be an expert, but says that in of all the interviews he conducted, not a single person said the foster care system was succeeding.

“I think anyone with a brain can see clearly that there is a huge amount of room for improvement,” Cretton said. “I hope that this movie creates more conversation around that.”