["The Other Side of the Rainbow: Young, Gay and Homeless in Metro Atlanta" is part 1 of a 3 part series on LGBT issues. Bookmark this page for updates.]

In April 2008, Brian Dixon was 18-years-old and homeless. Being gay, he says, only exacerbated his predicament.

After allegedly enduring years of mental and physical abuse, at age 14 Dixon left home to live with his grandparents. Within a year, they placed him in Georgia’s foster care system. From there he bounced around to several group homes. He’d quit high school, but earned a GED before officially “aging out” of the foster care system.

Dixon, who was born in Fort Benning about 90 miles southwest of Atlanta, had dropped to his knees many nights, fervently praying to be granted an extension to remain in the foster care system a bit longer while he worked on his nursing degree from Georgia Perimeter College. His new caseworker, whom Dixon describes as a “devout Christian,” was not in support. She’d convinced her superiors that he was not “a good candidate” for that privilege. He thinks it’s because he’s gay. Within two weeks, Dixon was dropped off with his few belongings at a Southwest Atlanta homeless shelter.

“I was scared; I had nowhere else to go,” recalls Dixon. “That first night they sent me to Covenant House and I just could not handle it. I was still in the foster care mindset. It didn’t really register in my mind that I was actually homeless.”

Strict rules and a curfew at the facility for those aged 17-21, didn’t mesh well with Dixon’s school and work schedule. He tried traditional adult shelters briefly, but ultimately ended up living on the streets of Atlanta. That catapulted him onto a yearlong emotional and heart-wrenching odyssey of illegal drug use, prostitution and “couch-surfing” from one friend’s house to another. He claims in the summer of 2009, he even fell victim to a brutal roadside rape at the hands of two strangers.

Atlanta-based licensed counselor Tana Hall says Dixon’s experiences are common among displaced gay youth.

“A lot of young people in this predicament get sexually exploited because of their homeless situation,” says Hall, who counsels Lesbian Gay Bisexual and Transgender (LGBT) youth at Atlanta-based non-profit, YouthPride. “A lot of young gay boys find themselves trading sex for basic necessities like food and shelter but they won’t tell you that. They’ll tell us, ‘I’m staying with this 45-year-old guy.’ They’re happy to have groceries and a place to stay, but they’re not admitting what’s really going on there.”

As Hall suggests, Dixon is among legions of LGBT teenagers and young adults kicked out of their homes and out of foster care homes primarily because of their sexual orientation. Many claim that the discrimination they face – often rooted in religious conviction – even extends to homeless shelters and into the foster care system. The ostracism, Dixon says, is magnified 10-fold for transgender youth whose androgynous appearance is often harder for others to embrace. Halls says she’s heard staffers at local Christian-based shelters make homophobic comments and it’s upsetting. She often tries to avoid sending her clientele there because she fears discrimination, but sometimes it’s the only option available.

“There’s a disproportionate number of homeless LGBTQ young people out there because of a lack of acceptance from their families and others around them,” says Hall, who also answers calls on YouthPride’s crisis hotline. She and other advocates however, often add an “I” and “Q” to the common acronym, in reference to “intersex,” persons born with both male and female genitalia and “questioning,” as in those questioning their sexual orientation.

“The majority of calls I get on our helpline are young people who have run away because they did not feel that they were accepted in their home,” Hall says. “The primary reason that these young people are homeless is not because of issues like substance abuse or mental illness; it’s due to a lack of acceptance about who they are [from others]. It’s a societal issue.”

Dixon claims the only facility he’s ever formally been kicked out of was one touted as a “Christian group home.” Upon arrival, he says, he was required to sign a form agreeing to never disclose his sexual orientation. He tried unsuccessfully to conceal his sexual identity there.

“People kept asking me about it and I wouldn’t answer them; once they found out I was gay, it was pretty much downhill from there,” recalls Dixon.

There is no publicly available source of data on the number of homeless youth in Atlanta. For that reason, it is impossible to estimate what percentage may identify as LGBT, concluded a national 2007

“There haven’t been many studies done on this segment of the homeless population so it’s hard to tell exactly how many are out there,” says Kathy Colbenson*, a longtime Atlanta-area advocate for LGBT youth rights. “Some estimates in New York City and California estimate that 25 to 50 percent of homeless youth identify themselves as LGBT.”

In January, Georgia marked a milestone with its first-ever attempt at counting a representative sample of homeless youth statewide. The results are expected to be released later this year. Funded by the Governor’s Office for Children and Families, the “Homeless Youth Count Project,” was part of a bi-annual census of homeless people of all ages as mandated by the Department of Housing and Urban Development. Questionnaires distributed in the city of Atlanta, DeKalb, Fulton and several other Georgia counties for the first time requested information specifically about homeless young people 24 and younger.

Homeless youth-focused non-profits CHRIS Kids and Covenant House advocated to get an LGBT question on the form, “but the state had a different opinion,” contends Colbenson. “We missed an opportunity to get some critical data for Georgia. On the forms we did get to ask if they were male, female or transgender.”

Nationally, LGBT youth are estimated to account for 20 to 40 percent of homeless youth in the United States, while only about 5 to 10 percent of the general youth population is LGBT, according to a 2010 study by the Center for American Progress, an LGBT advocacy organization. The report also attributes the high number of homeless LGBT youth to families shunning their gay and transgender children as they come out at younger ages. In New York, the report finds, 14.4 years old is the average age that a gay or lesbian youth becomes homeless.

In May, U.S. Senator John Kerry (D-Mass.) introduced legislation aimed at reducing youth homelessness — and, specifically, preventing homelessness among gay teens. The Reconnecting Youth to Prevent Homelessness Act would help develop programs to improve family relationships and decrease homelessness for LGBT youth. The measure pushes for improvements in training, educational opportunities and permanency planning for older foster youth, along with strengthening programs to reduce poverty and keep families together.

According to a 2009 national report by the National Coalition for the Homeless (NCH):

- 20 percent of homeless youth are LGBT. Comparatively, only 10 percent is LGBT in the general youth population.

- While homeless youth typically report severe family conflict as the primary reason for their homelessness, LGBT youth are twice as likely to have experienced sexual abuse before the age of 12.

- Once homeless, LGBT youth are at higher risk for victimization, mental health problems and unsafe sexual practices; 58.7 percent of LGBT homeless youth have been sexually victimized compared to 33.4 percent of heterosexual homeless youth.

- LGBT youth are roughly 7.4 times more likely to experience acts of sexual violence than heterosexual homeless youth.

- LGBT homeless youth commit suicide at higher rates, 62 percent; compared to 29 percent for heterosexual homeless youth.

The NGLTF report cited the Georgia Department of Human Resources (DHR) Division of Family & Children Services (DFCS) along with YouthPride and the CHRIS (Creativity, Honor, Respect, Integrity, Safety) Kids Rainbow Program as the chief public agencies and organizations working with LGBT youth in metro Atlanta. Colbenson, who serves as executive director of CHRIS Kids, says Covenant House also helps house displaced teens and young adults, including those who are LGBT.

The NGLTF report cited the Georgia Department of Human Resources (DHR) Division of Family & Children Services (DFCS) along with YouthPride and the CHRIS (Creativity, Honor, Respect, Integrity, Safety) Kids Rainbow Program as the chief public agencies and organizations working with LGBT youth in metro Atlanta. Colbenson, who serves as executive director of CHRIS Kids, says Covenant House also helps house displaced teens and young adults, including those who are LGBT.

“There are a couple of organizations doing a lot for the young LGBTQ community [in metro Atlanta] but not nearly enough,” says Covenant House Executive Director Allison Ashe. “Resources for homeless kids in general are scarce here. At Covenant House we have an open intake process at our crisis shelter. We have 15 beds and can overflow to 20 and we’re full every night.”

*Kathy Colbenson is the wife of Pete Colbenson, a JJIE.org contract employee.

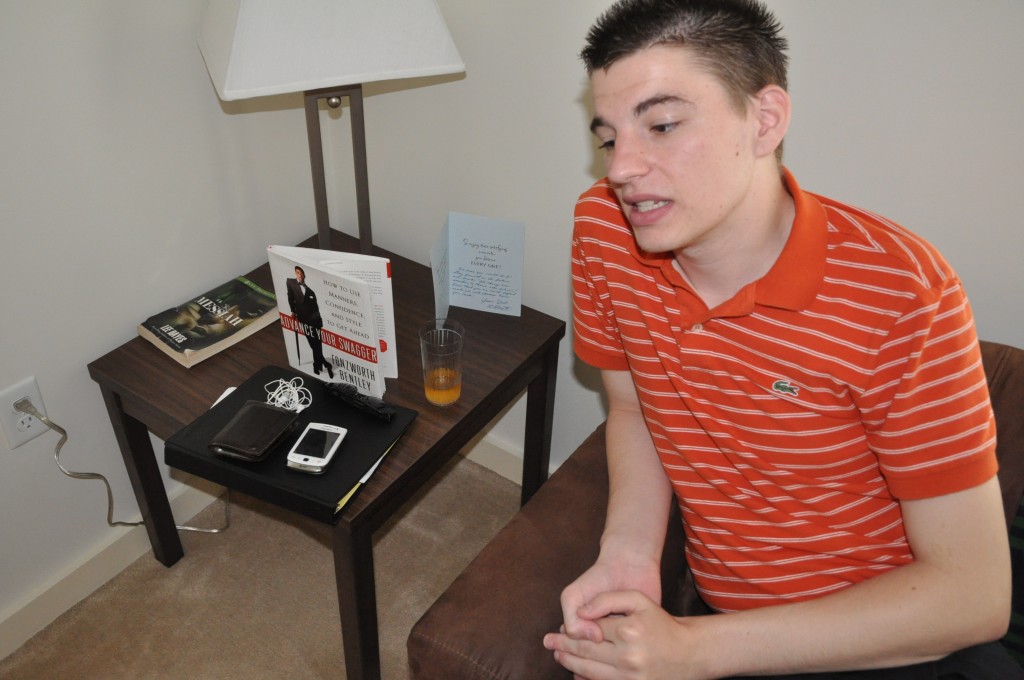

From looks alone, you’d never think Dixon had endured all that he has in barely two decades of life. Almost everything about him seems contradictory. His clean-cut boyish looks and sunny demeanor don’t seem to jibe well with his dramatic story — an epic ideal for a made-for-TV movie. His milky complexion belies his part Puerto Rican heritage. He’s tall and lanky, but tends to recoil slightly — like a child in protective mode — when he speaks of the emotional and physical traumas he’s experienced. His grammar isn’t perfect, but his words convey a wisdom that far exceeds his age. What’s most fascinating, though, is his unyielding Christian conviction. It’s particularly interesting in light of the fact that he contends that so many people in his life refer to the Bible as the basis for condemning him and his “lifestyle.” He’s well aware that he’s been dealt a bad hand in life, so to speak, but he presses on with the determination of someone holding a full house, poised to claim victory in the card game of life.

“I’ve just always had this sense that God has something better for me,” he says, a hopeful smile spreading across his face. “That’s what has kept me going.”

He’s built a surrogate “family” of friends and church members from The Vision Church of Atlanta (Dixon calls it a “progressive Pentecostal” congregation) and together, with them, he continues his pursuit of that “something better.”

Dixon now calls a quaint one-bedroom apartment in East Atlanta home. Summit Trail is a maze of five pristine brick buildings, traced by patches of vibrantly colored flowers and fluffy green grass. His place is tidy and smells of Febreeze, which he admits to obsessively spraying daily. The bright gold chair in the corner, the chocolate brown microfiber couch pressed against a large sun-drenched window and even the colorful abstract painting that hangs solo on a side wall were all charitable donations from CHRIS Kids supporters.

Dixon now calls a quaint one-bedroom apartment in East Atlanta home. Summit Trail is a maze of five pristine brick buildings, traced by patches of vibrantly colored flowers and fluffy green grass. His place is tidy and smells of Febreeze, which he admits to obsessively spraying daily. The bright gold chair in the corner, the chocolate brown microfiber couch pressed against a large sun-drenched window and even the colorful abstract painting that hangs solo on a side wall were all charitable donations from CHRIS Kids supporters.

Aside from being the only place that Dixon says he’s ever felt was truly his own, this “supportive housing” facility operated by CHRIS Kids is unique in that it is the only one of its kind in the Southeast that specifically supports young gay, lesbian and transgender adults. The apartment community houses single and “parenting” youth, ages 17 to 24, with emotional and behavioral problems who are aging out of foster care, as well as homeless youth.

“We provide special outreach to LGBT youth, as they represent a disproportionate number of homeless youth,” explains Colbenson. “This facility is the only program in the Southeast that specifically reaches out to help and support young adults who identify as gay, lesbian and transgender. There are other programs out there, but none doing it in an apartment complex setting like we’re doing it.”

Dixon, like all of the young adults who live at Summit Trail, take part in TransitionZ, a life skills program that provides counseling, educational support and job skill development.

“We’re providing them with the skills they need to become contributing citizens,” says Colbenson. “We’re not in the business of enabling, we’re in the business of second chances. It’s all about self-sufficiency. All residents have to be working or going to school.”

In 2009, after a year on the streets, Dixon landed a precious slot at one of the tiny six-bed residential facilities where CHRIS Kids had operated since 2000. He remained there until last year when he and all of the other residents moved into the considerably larger East Atlanta complex. Summit Trail houses up to 44 young adults and up to 16 of their children. Since it is federally subsidized, the rent is based on income and residents must adhere to strict rules. For example no alcohol or smoking is allowed; all guests must undergo a background check to visit.

YouthPride is the only metro Atlanta organization that serves all LGBT teens and young adults ages 13 to 24. From its downtown Atlanta facility the staff provides counseling and group support sessions. Until recently, it had operated a program called Home@YouthPride that intervened with direct emergency assistance (such as cash or vouchers) to prevent eviction or help place a young person temporarily in a safe place. Hall says limited financial resources led to the program’s demise. She and her staff now do what they can to divert their clients to other available resources, primarily CHRIS Kids and Covenant House.

“Adult shelters aren’t necessarily the safest place for kids,” says Ashe. “A lot of child predators tend to hang out in shelters looking for kids to prey on. That’s why we need more options available in the city for young homeless kids and young adults.”

Most advocates agree Atlanta could do a better job in regards to its support of its homeless LGBT population. In fact, in 2006 the NCH named Atlanta the fourth “meanest city” in the nation regarding its treatment of homeless people.

Most advocates agree Atlanta could do a better job in regards to its support of its homeless LGBT population. In fact, in 2006 the NCH named Atlanta the fourth “meanest city” in the nation regarding its treatment of homeless people.

“Georgia has come a long way, but it has a long way to go,” notes Colbenson.

Ironically Dixon says a lot of LGBT young people flock to Atlanta from across the country and the Southeast because of its prevalent image as a “gay friendly city.” Once here, he says, there’s often a rude awakening.

“I pray that I live to see the day when Atlanta and the South become an affirming, more accepting place no matter who you are and where you come from,” says Dixon. “Dr. [Martin Luther] King said an injustice anywhere is an injustice everywhere. We need to finish Dr. King’s work.”

Hall agrees.

“Atlanta is a gay friendly city for adults with money; if you’re white and privileged like me,” asserts Hall. “I live in Decatur [next to Atlanta] and there are so many lesbians here. If you have a job and money it’s easy to be gay here, but not so much if you don’t fall into that category.”

Once relegated to the streets for that year, Dixon says he, like many displaced LGBT youth, resorted to selling sex in exchange for food and places to stay. Soon thereafter he flunked out of college and was strung out on methamphetamine, cocaine and heroine.

“The only thing I didn’t get into was needles,” remembers Dixon. “I didn’t like needles.”

Dixon’s life was steadily spiraling out of control. His religious faith, however, remained a source of strength.

“I might have been at the club all night, but you best believe on Sunday morning I’d be at church,” says Dixon, with a giggle. “Then one day I’d had enough. I got really tired. I told God, ‘I can’t do it no more.’ A lady at my church walked up to me that Sunday and said; ‘God told me you’ll never be the same after today.’ I never touched any of it ever again. To this day I’ve been clean for over two years.”

The graduation card propped on his end table this breezy Tuesday afternoon, Dixon says, is from his openly gay pastor, Bishop O.C. Allen at the Vision Church in East Atlanta. The message printed inside reads, “Congratulations, you’re the kind of person who makes the world a better, brighter place.” He takes those words to heart.

At 21, Dixon is more hopeful about his future. His parents have been divorced for years. He speaks to his mother occasionally by phone, but he never communicates with father, a former Pentecostal minister. He’s unemployed now, but the nursing assistant certificate he received from Woodruff Testing Center in Decatur in March keeps him motivated on the job hunt. Dixon hopes to continue his education and one day open up a medical care facility for LGBT HIV/AIDS patients. Interestingly enough, he’s also soon to begin the process of becoming a Pentecostal minister — just like his dad once was. He shrugs off the comparison.

“I know that I’ve been called by God to preach,” he says. “I walk in a prophetic calling to preach love and acceptance for all people. That’s my goal and that’s what I’m going to do.”

-- Continue to From the Staff: The ABCs of LGBT-->

-- Jump to Ideas and Opinions: Ty Cobb On Safe Schools for LGBT Youth -->

[NEXT: Part 2 of a 3 part series on LGBT issues, "Double Jeopardy: Lesbian Activist Says Fear of Parents’ Homophobia Inspires Secret Life." Bookmark this page for updates.]

Photography by John Fleming, JJIE.org.

*Kathy Colbenson is the wife of Pete Colbenson, a JJIE.org contract employee.

Ms Thomas,

My name is Angele Hawkins and I am the Executive Director of New Hope Enterprises.

We are an agency that works collaboratively with many existing non-profits in Atlanta. Agencies like CHRIS Kids do a phenomenal job with the presenting problems of the LGBT youth. CHRIS kids is one of our referral partners and as such once Brian’s housing issues were addressed, he came into our program. We offer a four week job readiness program followed by hard skill tracts that are designed to be put people onto vertical career paths.

Brian is a graduate of our STRIVE program. We then placed him at Woodruff Medical for an opportunity to get a CNA Certificate. As an agency we not only paid for the CNA tuition, but two sets of scrubs, hospital appropriate shoes, stethoscope and all the testing fees needed to get certified. In addition, we work with all of our graduates on job placements.

I appreciate your thoughtful article on Brian’s challenging journey. I want to make sure that you and others realize that we at New Hope consider ourselves part of the solution as we help young people aging out of the foster care system and the juvenile system.

Thank-you,

Angele

Angèle Hawkins, founder

Executive Director

NEW HOPE ENTERPRISES

970 Jefferson Street

Atlanta, GA 30318

404.671.3560 ext 221

http://www.newhopeenterprises.org

Hey Chandra and those who are reading this I am pleased with the ariticle you all did on me! I want to thank you for allowing me to share my story and getting to let others know their is light at the end of the tunnel no matter how dark the situation may seem! I hope that this story encourages others to keep on pushing ahead and never to give and allows those who can help those in need and to show kindness to people regardless of who they are!

Blessings,

Brian

Hi,

its so commendable job that you are doing. We really appreciate your good work.

I am owner of LGBT based Travel Firm named Out journeys we are members of IGLTA and we always try and give back to the community that we work for. We are associated with Mingle(Mission for Indian Gay and lesbian empowerment)

We are really glad and proud of people like you.