Clay Duda / JJIE

SOS Outreach Workers (from left) Derick Scott, Achisimach “Chis” Yisrael, David Bookhart and Lavon Walker cruise the streets of Crown Heights looking to strike up a conversation. Being both positive influencers in the community and credible messengers with similar pasts are key to helping shape the neighborhood’s future.

NEW YORK -- “I want these gang members to know it ain’t the only way,” Rico, a 27-year-old standing in the doorway of a dusty bodega on Kingston Avenue in Brooklyn, said. A long-time member of the notorious Blood street gang, Rico said it had been months since he picked up a gun – a change in lifestyle he attributed largely to the positive influence of a handful of guys from the neighborhood.

Katy McCarthy / JJIE

This story is part of a series of articles exploring Community-Based Alternatives. Read more from the series here.

Outside the Albany Homes housing projects a few blocks down, a 20-something-year-old who refused to give his name, had a similar story.

“I thought for this man the other day. I had a thing for him [wanted to hurt him], but I stopped myself,” he said.

It’s small victories like these the outreach workers of Save Our Streets (SOS) Crown Heights work toward everyday, dedicating their time to act as role models and mentors in an attempt to tamper the spread of gun violence within a 40-block area of central Brooklyn. A walk down the street can be a testament to the work done by Lavon Walker, David Bookhart, Achisimach “Chis” Yisrael and Derick Scott each afternoon as they comb the community, and a reminder of the high stakes at play.

Clay Duda / JJIE

A makeshift memorial for “Drizzy,” an 18-year-old who was the latest victim of gun violence at our visit, sits on a Crown Heights street corner across from a small bodega in Brooklyn.

Around the corner from Albany Homes, leaning against a light pole, is a makeshift memorial for Drizzy, who barely a month before, at age 18, became the most recent local casualty of gun violence. A few empty bottles and scrawls of "RIP" on water-logged pieces of cardboard were all that some of his friends had to remember him by.

Like many urban neighborhoods, parts of Crown Heights suffer from the image, and sometimes the reality, of high violent crime rates. SOS, however, aims to change the image and the reality of life in the neighborhood with a unique approach. They treat gun violence like a disease.

It’s a method known as the CeaseFire model, sculpted after an evidence-based initiative in Chicago that had shown results over the past decade. [Editor's note: After JJIE reported this story, Ceasefire Chicago changed its name to CureViolence.] The approach confronts the problem head-on, working to establish a culture that speaks out against violence through an emphasis on community interaction, conflict mediation and other tactics in a troubled neighborhood with high levels of violence.

“The Chicago CeaseFire model is a public health approach,” Amy Ellenbogen, director of the Crown Heights Mediation Center, said. “If you can get to the people spreading the gun violence – keeping with the analogy that gun violence is like a disease – then you’re going to have a positive impact.”

It’s a program that showed enough promise in Chicago to be replicated in more than a half-dozen inner-city neighborhoods around the country, in places like Oakland,

It’s a program that showed enough promise in Chicago to be replicated in more than a half-dozen inner-city neighborhoods around the country, in places like Oakland, Boston, Phoenix, New Orleans and, most recently, Richmond, Va.

In Boston, a group of Harvard researchers paid close attention after the city decided to re-launch its CeaseFire program following a rash of gang shootings in the mid-2000’s. An earlier rendition of the program had shown strong, but not well documented, results. Among the 19 targeted gangs, between 2006 and 2010, shootings dropped at nearly three times the rate of gangs not in the program – meaning Operation Ceasefire participants were less likely to shoot and be shot at. [Editor's note: The Boston Ceasefire program was, in fact, a different model that shared the same name as the program in Crown Heights.]

The killing hasn’t stopped in any of the troubled city neighborhoods focused on by the independent nonprofits, but in many cases the number of shootings and number of people who have been shot at have dropped over the years.

Still, other places have struggled to achieve the same results. A similar program in New Orleans’ crime-ridden Central City neighborhood actually saw an increase in violence since launching in mid-2012. But officials remain steadfast that the program can work in New Orleans just as it did in other parts of the country – given enough time.

Overall, the Crown Heights program has helped lower the number of shooting incidents in the neighborhood, but has struggled to keep the downward pace over the past year. However, its success has been enough to rally financial support for a sister program in the South Bronx. There, city officials hope to see a similar decline in the months and years ahead.

Out of That History

Clay Duda / JJIE

SOS Outreach Workers Derick Scott and Lavon Walker cruise the streets of Crown Heights looking to strike up a conversation. Being both positive influencers in the community and credible messengers with similar pasts are key to helping shape the neighborhood’s future.

The Crown Heights neighborhood has grabbed a few headlines over the years. Some of the most impactful followed unsavory moments in the community’s history: a three-day riot in 1991 divided along racial and religious lines, and a police corruption scandal that left the 77th Precinct, which covers the area, in shambles back in the 1980s.

But those incidents were decades ago, a time one New York Times writer called “a different era in New York.” Today, Crown Heights is still a bustling neighborhood of storefronts, five-plus-story apartment homes, synagogues, churches, parks, bodegas, schoolhouses and neighbors.

Although the tensions that led to the unrest in 1991 have cooled, the demographic and social make-up of the neighborhood hasn’t changed much in the past two decades. It still boasts large African American and Hasidic Jewish communities, and still has a large number of children growing up below the poverty line – more than 30 percent of 7- to 21-year-olds according to data from the Center for the Study of Brooklyn at the City University of New York.

Learn more about Community-Based Alternatives at the Hub

Throughout the 1990s and into the new millennium, instances of violence declined in Crown Heights and New York as a whole, according to police data. It was an encouraging trend for a neighborhood that has long struggled with the noxious cocktail of extreme poverty, street gangs and easy access to firearms, but by 2007, violent crime began to tick up again.

With a rising number of incidents, members at a local nonprofit already dedicated to helping the community with issues like pregnancy and truancy prevention, community-based mediation for disputes and limited efforts to reduce gun violence – among other things – saw the need to do more.

In 2009, a chunk of federal stimulus money allowed the nonprofit to expand its community outreach work and focus on reducing gun violence, specifically. The gift allowed New York’s Center for Court Innovation and Crown Heights’ Mediation Center to bankroll the Save Our Streets program and hire nine full-time staffers to work out of its small storefront on Kingston Avenue. Today, the program continues to be funded by a mix of federal, state and nonprofit contributions.

Since hitting the streets in early 2010, SOS has helped reduce the number of shooting incidents in its 40-block catchment area, the section of the community it concentrates its efforts on. The number of victims dropped at an even greater rate, although 2012 saw an end to the downward trend seen the first two years of the program. That year still saw 24 fewer shooting victims than in 2010, with the number of victims falling from 73 to 49.

Since hitting the streets in early 2010, SOS has helped reduce the number of shooting incidents in its 40-block catchment area, the section of the community it concentrates its efforts on. The number of victims dropped at an even greater rate, although 2012 saw an end to the downward trend seen the first two years of the program. That year still saw 24 fewer shooting victims than in 2010, with the number of victims falling from 73 to 49.

In the Streets and Withstanding the Heat

Taking a public safety approach offers a systematic framework for groups like SOS to identify and, hopefully, head off the spread of violence before it occurs, and limit the impact when it does. Like the Chicago model, SOS singles out the highest-risk individuals – those most likely to be shot or shot at – through the out-in-the-streets, hands-on work of the outreach workers.

When violence breaks out SOS dispatches interrupters to the scene, a group of community members who jump into the action in an attempt to calm high-tension conflicts and “beefs.” If the violence interrupters were firefighters, Project Director Ellenbogen said, “they’d be the ones jumping out the planes to put the fire out.”

“The best mediators are able to get into the heat of anger that’s involved in a dispute and they’re able to sit in the fire with the disputants without being consumed by it,” SOS Program Manager Allen James said. “Well this is a hotter fire than the average [situation].”

Clay Duda / JJIE

Crown Heights Mediation Center Director Amy Ellenbogen sifts through statistics of shooting incidents within the group’s 40-block catchment area. 2012 saw a slight uptick in violence following two years of decline, but the overall number of shooting are down since the program launched in 2010.

“I think that’s really why CeaseFire works,” he said. “Because you employ a bunch of people that are similar to local community health workers who get in there and they can stay in the fire longer than an outsider could, or someone uninitiated to that life.”

Those are direct interventions, but SOS also works with local businesses, community leaders and religious organizations to spread its message of nonviolence. For some, shootings have become just another fact of life in Crown Heights – but SOS workers want them to know it doesn’t have to be that way.

It starts with outreach workers working to identify which people in the community are most likely to end up on either end of a gun.

They look at a number of factors to determine each individual’s risk level: Do they carry a weapon? Do they know somebody that has been shot in the past 90 days? Are they involved in a street organization or gang? Do they have a history of violence? Recently released from prison? Fall between the ages of 16 and 25?

If the person meets four or more of the qualifiers, they’ll likely be added to one of the outreach worker’s caseloads. Kids under 16 may be encouraged to get involved with Youth Organizing to Save Our Streets (YOSOS), a program specifically tailored to have an impact on and educate younger demographics.

If the person meets four or more of the qualifiers, they’ll likely be added to one of the outreach worker’s caseloads. Kids under 16 may be encouraged to get involved with Youth Organizing to Save Our Streets (YOSOS), a program specifically tailored to have an impact on and educate younger demographics.

After identifying some of the most at-risk individuals, outreach workers do their best to work with those men and women on an ongoing basis and change their outlook on violence.

“One of the biggest challenges is overcoming the years and years and years of confirmation that nothing can change,” Achisimach “Chis” Yisrael, a former SOS Outreach Worker, said, seated behind the large conference table in the Mediation Center. “It’s a hell of a thing when you’ve got to go and step in front of individuals that were born, constantly reminded, with the belief that this is as good as it gets.”

“As far as the community, it’s almost the same challenge,” he said. “This is a community [that], although [they] don’t engage in those [violent] activities, watch these individuals that do and think there’s no changing them.”

The Mediation Center, where SOS is housed, still offers a number of services besides violence prevention that community members have come to rely on over the years. If a person is persuaded to take a different tack in life, or is recovering from a shooting, for example, they still often need help on a path to a safer and more stable future. The Mediation Center refers people to services which provide job training, educational support and teach basic social skills, many of which spill over into the work of SOS and help lay a foundation for more positive outcomes for some at-risk individuals working to overcome their challenges.

Clay Duda / JJIE

Rico, 27-year-old member of the notorious Blood street gang, greets Save Our Streets outreach workers as they walk down Kingston Ave. in Crown Heights, Brooklyn, New York. Rico would only give his street name, but credits the work of Achisimach “Chis” Yisrael (left), Derick Scott, and others for helping him find a life beyond the gang.

It’s an aspect of the program Rico, the long-time Blood gang member, said helped him to find a different way of living and earning money. “These brothas right here, they’re the truth,” he said. “Everything they do is realistic. They don’t just drop you into a job, they help you get a job.”

And through continuous support, that’s the kind of outlook SOS hopes to instill. The immediate goal is to temper tempers and reel in hostile disputes before they get out of hand, but the ultimate goal is a change in the way these individuals view and interact with the world.

“A lot of people have experienced failures from other programs in the past,” outreach supervisor Lavon Walker said. “So it’s up to us to really put it out there that we’re a different program and we are going to be successful – and it’s been proven to be successful.”

He continued: “The evidence has spoken for itself with the mindsets that we changed, the shootings that we were able to stop and the mediations we were able to accomplish. And that’s what we use to, also, try and get other people to buy in to what our movement is, to what our message is.”

The Credible Messenger

Part of the outreach workers’ success comes from their other title, that of a “credible messenger.” All of the guys grew up in the community, have similar backgrounds to a lot of the high-risk young people they work with, and have been forced to face many of the tough decisions the highest-risk individuals face every day.

Similar backgrounds could mean having spent time in jail or prison, running with a street gang in their younger years or just growing up in tune with the street culture that dominates the community’s social sphere. These factors and others help add credibility to the advice they give and the work they do, going a long way to build trust and rapport. These aren’t well-to-do outsiders telling poor people how to live their lives, but rather people from the community others could, potentially, relate to.

“They say man sharpens man, and steel sharpens steel,” outreach worker Derick Scott said. “It’s about time you have a bunch of guys that care about individuals in the street, that have a passion, because real recognize real.”

Scott has done volunteer work in some capacity or another since high school, he said, but “at the same time I was still doing dirt in the streets. I was one leg on the fence, one leg in the dirt.”

Eventually landing in prison, he said his “eureka” moment came the first time he walked into the prison cafeteria. That’s when he started to change, ultimately shifting his focus in life to helping others do the same.

“That was my rock bottom, so to speak – looking around that mess hall,” he said. “I went back to my cell, and I started to … I broke down.”

“I would teach the young guys that just because you’re in one prison doesn’t mean you have to be in another prison. This is a physical prison,” he said. “Most of us were more locked up on the outside, because we continued to do the same things over and over and over again, but expected different results.”

“So my place for change and changing the mindsets [of others], started in prison, and I brought it back out here,” he said, hoping he can keep others from following in his footsteps.

A Month Since Drizzy

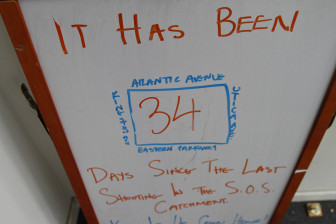

Clay Dude / JJIE

A whiteboard in the SOS office keeping count of the number of days since the last shooting in their catchment.

Still, the outreach workers are quick to say they couldn’t do the work alone. They are just one of the components in a system working to change the cultural norm and ways a part of society perceives violence in its lives. Partnerships with local businesses, religious outfits and community organizations are key.

Clergy leaders regularly incorporate messages of anti-violence into their sermons and, at times, work as a liaison between SOS and community – especially when particularly heart-wrenching incidents occur. Dozens of businesses around the area sport SOS signs in their windows, counting the days since the last shooting incident.

At the time of our visit, it had been 34 days since Drizzy was shot and killed – the most recent victim. That’s not a bad record, considering the neighborhood’s history. Still, it won’t stop neighbors, community leaders and the dedicated workers trying to Save Our Streets from striving for more. Tomorrow they will wipe off the dry erase board and write "35" – and count toward a brighter and safer future.

Pingback: Monday Links: More Atonement! Plus Interrupting Violence, Texification of the Church in America, and More

I’m a father trying to raise young men (my sons) from turning to the streets. I was reading this articles and was moved. I’m in ATL and I want to know if there is a program like this here. I want to get involved, I want my sons to be involved….please contact me.

a Father