Early one morning a few weeks ago, the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth team boarded a bus to New York for a re-sentencing hearing for a young man who was sentenced as a child to mandatory life without parole.

Early one morning a few weeks ago, the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth team boarded a bus to New York for a re-sentencing hearing for a young man who was sentenced as a child to mandatory life without parole.

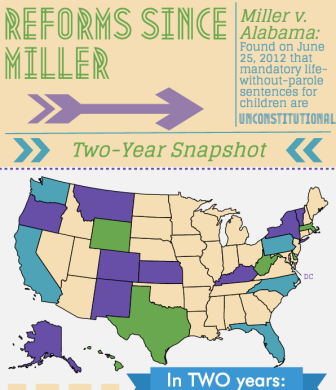

Angel was sentenced after he was charged and convicted in federal court for his role in a gang-related homicide after he, at age 15, rode his bike around the block as the lookout outside the home of a man who became the victim in an execution-style killing. Two years after the Supreme Court’s landmark decision in Miller v. Alabama, which found that it is unconstitutional to impose automatic life-without-parole sentences on children, I find myself reflecting on the hearing as a poignant illustration of where we are in this movement to establish fair sentencing for children.

Angel’s childhood was riddled with neglect, trauma, extreme poverty and violence. Both of his parents were addicted to drugs and, in a search for love, respect and support, he found the streets and was lured into a gang at a very young age. These facts about Angel’s life are among the key factors Miller now requires judges to consider at sentencing. Angel was offered a plea bargain of 15 years, but like many teens who lack the sophistication of dealing with the criminal justice system, he turned it down. Instead, he exercised his constitutional right to a trial and his presumption of innocence. He was penalized for that and at Angel’s original sentencing hearing, the judge said that even if she had a choice, she would give him a life sentence for his role in this horrific crime.

And in May 2014, 16 years later, Angel went back before that same judge. In preparation for the hearing, we worked with Angel’s defense team, who did a terrific job tracking down relevant information about Angel s life history and his progress during his time in prison. The team recruited experts and interviewed family members and former teachers, all in an effort to demonstrate that the young boy who made a grave mistake is worth more than the worst thing he has ever done. He has changed since then; he has matured, realized the consequences of his actions and is deeply remorseful. The defense recommended his sentence be reduced to 20 years.

The U.S. government — the prosecution in this case — conceded in its briefs that children have the capacity to change and that factors relevant to a child’s age, maturity and potential for rehabilitation now must be considered in the context of sentencing. But they focused on the facts of the crime and argued that Angel still deserved to serve 27-32 years in prison. The department of probation, an agency that is supposed to weigh in with a sentencing recommendation after interviewing all parties, urged a sentence of 25 years.

Prior to the court appearance, a lawyer in New York took Angel’s case on pro bono, filed an amicus and engaged a broad array of stakeholders to sign on. The brief described recent advances in our understanding of adolescent development, recidivism among children and past mistakes made by criminologists that led to these extreme sentences for children. Angel’s family and friends also wrote letters of support. And the family members of the victim in the case wrote to share their feelings of pain, anger and horror about this case being reopened.

That morning, we arrived at the courthouse about 30 minutes before the hearing started. Angel’s family flooded the hallways — his mom, grandmother, sister, stepmom, aunts, uncles, cousins. There were probably 30 of them there. I greeted them and then made my way into the courtroom to introduce myself to his lawyer, with whom I had spoken with many times by phone but never met in person. Two women in tears were already seated in the courtroom and were accompanied by a social worker. They told me this whole process was reopening old wounds for them, and that it wasn’t fair for them to go through this again. I said I was sorry for their pain and that I could connect them with other victims’ families going through this, if that was of interest to them. I was at a loss for what else to say or do. No response to this (very understandable) raw emotion seemed adequate.

A little while later, everyone filed into the courtroom and was seated. Angel’s family was on one side, and the victim’s family was on the other; various other interested parties filled the rest of the seats. The courtroom was packed, but silent and still. Eventually, the U.S. Marshall brought Angel in, wearing a blue jumpsuit and long-sleeved undergarments. He stood, at just about my height of 5 feet 5 inches, between his two defense attorneys. One of them leaned over to him and pointed behind him to the seats where his family and we were quietly, anxiously, awaiting his fate. He broke down in tears.

The judge finally entered. We all rose. She began by explaining why we were there: Recent Supreme Court cases mandate that she re-sentence Angel and consider factors about his age, life and character that she was not allowed to consider previously. Her tone was harsh, as she described the facts of the crime, which she said were permanently seared in her brain. She called Angel an "enthusiastic member" of the "death squad" that killed an innocent man and wreaked havoc on his family.

Each attorney argued his side briefly. Then a sister of the victim got up and spoke. Through tears, she told the court that her family had been torn apart by this crime and forever haunted by the gang that killed her brother and terrorized her loved ones. Angel could not hold back his own tears when she talked about the pain to which he contributed. He spoke next. He apologized to the victims and said that for the rest of his life, he will carry deep regret and remorse for the harm he caused. He said that while he cannot bring the victim back, he will dedicate his life to giving back and compensating for his actions as a young teen.

The judge took us all on an emotional roller coaster, sharing aloud her deeply conflicted feelings about how to handle this case. She dramatically called out the name of the victim over and over again. Then she commended Angel on his progress in prison. She said there would be "no justice" in this case — that wasn’t possible. She wanted to send a message to people in Angel’s "communities" that gang violence, even by young people, deserved severe punishment. Throughout the judge’s angry tirade aimed at Angel, his mother sat behind me sobbing.

Finally, nearly an hour into the hearing, the judge said that when she feels totally conflicted about what sentence is most appropriate to hand down, she generally defers to the probation’s recommendation. In this case, that was 25 years. With good time credit, Angel will be released in approximately six years, at age 41. In contrast, older people who were involved and had a much larger role in the crimes received much shorter sentences because they agreed to work with the government. For example, the person who obtained the gun and was part of the “execution team,” according to the government’s brief, was sentenced to seven years. The person who oversaw planning of the murder was sentenced to 90 years. And the person who provided the gun and helped with the planning was sentenced to time served at the time of plea agreement plus 30 days.

I looked at Angel to gauge whether this was devastating news or a relief. His mother continued to sob. But after the judge left the courtroom, Angel finally looked up with a glimmer of hope in his eyes, clearly thankful for the outcome. A 25-year prison sentence seems like a long time to me given his age and role in the crime, but after hearing from this judge, I was grateful she didn’t just give him life again. Mostly, I was glad that even though he was told as a teen he was worth nothing more than dying in prison, Angel now has a release date.

Angel was escorted out of the courtroom and smiled and nodded toward his mother and grandmother on his way back to the holding tank, where he would await transport back to the jail in Brooklyn, and eventually back to federal prison, as far away as Texas, to finish out his term.

The next day I received this message from Angel:

“Well today is the first day in 16 years that I woke up and I actually have a release date, of course it is not certain yet since I have to get the prison to calculate but I have a date. Thank you for all of the support and encouragement. It has been a long road and now I am ready to show the rest of the world that this is not who I am but a small hurdle that I had to overcome. I have truly changed since I have been in here and now I can start living. I still have a lot to work on especially after hearing what the victims family had to say about me but I know that that will come in time. Again thanks for your thoughts and prayers and everything in between. The count down started yesterday at about 2pm and I can see the horizon :)”

The day and the months leading up to Angel’s hearing involved much pain, anxiety and sadness. For everyone. I agree with the judge about one thing: There is no justice in this case. There is no justice in an innocent man being killed. There is no justice in the victim’s family suffering and having wounds reopened after they thought the case was closed. There is no justice in the life sentence imposed on Angel. There is no justice in imposing a 25-year sentence on a 15-year-old kid who was riding his bike as a lookout for a gang he ran to in place of a family. There is no justice in a child being neglected and abused, yearning for belonging and finding it in a gang. There is no justice in his mother’s addiction or the shame she continues to carry with her. There is no justice in this case.

There is no justice in the fact that two years after Miller, people who should be eligible for relief are still serving this sentence, as states grapple with whether the decision should be applied retroactively, and others continue to impose this sentence upon children. There is no justice in short-sighted, narrow reforms being made by some legislatures and courts to replace mandatory life-without-parole with de-facto life terms. And for people who lose family members to crimes of violence, there is no justice in the lack of funding and supportive services invested in their healing and restoration. Clearly, there is more work to do.

But there are signs that we are nearer to justice than even two years ago, some more tangible than others. The majority of state supreme courts that have taken up Miller retroactivity have ruled that the decision should be applied to those currently in prison serving mandatory life-without-parole sentences for crimes committed as children. Delaware, Hawaii, Massachusetts, Texas, West Virginia and Wyoming have responded by abolishing the practice. Five other states have eliminated JLWOP for certain categories of children. At the same time, we are seeing growing broad support for reform as more national organizations, policymakers, editorial boards and opinion leaders, ranging from President Jimmy Carter to former Speaker of the House Newt Gingrich, call for changes in our juvenile sentencing laws. Pope Francis has also added his voice to the issue, noting his concern for the people serving this extreme sentence.

And, perhaps most importantly, people like Angel now have release dates and renewed hope that inspires us all to continue on in this marathon toward justice.

Jody Kent Lavy is Director of the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth.

Pingback: Signs of hope and justice two years after Miller v. Alabama

Rick Wershe is currently serving a life prison sentence in the Michigan Department of Corrections for a single non violent offense (drug possession) from 1987. When he was arrested he was only 17 years old.

http://clemencyreport.org/richard-wershe-jr-named-michigans-no-1-inmate-deserving-clemency/

http://www.thefix.com/content/story-white-boy-rick-richard-wershe-detroit-corruption70041?page=all

http://www.ticklethewire.com/2013/09/11/column-the-michigan-parole-boards-crime-against-white-boy-rick/

http://www.gorillaconvict.com/2014/06/white-boy-rick/

http://www.detroitsports1051.com/drewlanepodcast/2014/01/15/white-boy-rick-from-oaks-correctional-facility

https://www.facebook.com/freewhiteboyrickwershe

http://freerickwershe.com/Home_Page.html

http://www.change.org/petitions/free-white-boy-rick-wershe

https://twitter.com/freerickwershe