While the man behind the landmark decision that ended mandatory life-without-parole sentences for juveniles waits for a new sentence, other inmates given the same term are getting a shot at eventual freedom.

Evan Miller went back before a judge in his hometown of Moulton, Alabama, for a three-day resentencing hearing March 13. Lawrence County Circuit Judge Mark Craig’s decision is still pending.

But the Supreme Court ruling that bears Miller’s name is already bearing fruit for other Alabama inmates serving life without parole for crimes they committed before they were 18. For them, the process can be difficult, slow and vary county by county. And thanks to a 2016 state law, they may have a long wait for a parole hearing even if they succeed.

For example, the July 31 decision declaring juvenile lifer Richard Kinder eligible for parole came nine months after a hearing before a judge in Birmingham, attorney Richard Jaffe said.

“The judge wanted to be thorough and know every inch of it — every document, every record, and there were thousands and thousands of pages,” said Jaffe, who defended Kinder in his 1984 trial and served as co-counsel in his resentencing.

Joy Patterson, a spokeswoman for the Alabama attorney general’s office, said about 70 other state inmates are eligible for new sentencing hearings under the 2012 Miller v. Alabama decision and its 2016 follow-up, Montgomery v. Louisiana, which declared the Miller ruling retroactive.

So far, 20 of them have been resentenced to life with a chance at parole, said Eddie Cook, a spokesman for the Alabama Board of Pardons and Paroles.

State Rep. Jim Hill, a former judge who pushed to bring Alabama’s capital sentencing law into line with the Miller decision, said he has urged his old colleagues to get on with the task at hand.

“I have certainly had judges call me and ask, ‘Do I need to have rehearings?’ And my answer to them is, ‘Sure. You must. Go ahead and schedule it and get it done,’” said Hill, a Republican who chairs the state House Judiciary Committee.

Alabama’s new capital sentencing law, passed in 2016, also requires that teens convicted of capital murder serve 30 years before becoming eligible for release. Since Kinder has been imprisoned more than 30 years, he now has the right to a parole hearing, Jaffe said.

But other juvenile lifers will face more years behind bars even if they succeed in getting their chance at parole. That would include Miller himself, who was convicted in 2006.

That 30-year requirement isn’t the most stringent, according to The Sentencing Project, a Washington-based research and advocacy organization. At least two states — Texas and Nebraska — require a 40-year minimum. But it’s tougher than others: West Virginia allows inmates to get a hearing after 15 years; Nevada, 20; and South Dakota leaves the issue entirely up to a judge.

And the Miller decision barred only the automatic imposition of a life-without-parole sentence for a teen killer. Judges can still hand down that term after weighing the evidence. But the justices required them to consider a teen’s "diminished culpability and heightened capacity for change," and the follow-up Montgomery decision limits the punishment to teens whose crimes show “permanent incorrigibility.”

“It’s going to apply to the rarest of the rare cases,” Jaffe said.

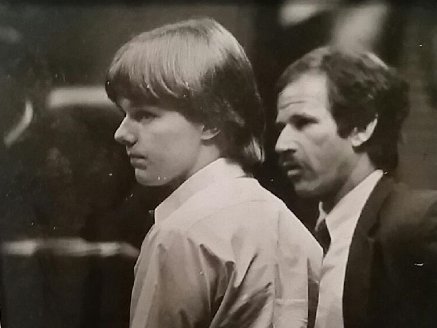

Alabama Department of Corrections

Kinder has served nearly 33 years of a life-without-parole sentence for a killing committed when he was 17.

Kinder, then 17, was convicted of capital murder in the 1983 killing of 16-year-old Kathleen Bedsole during a robbery and kidnapping. As an accomplice, Kinder was spared the death penalty, but got life without parole. The 21-year-old gunman, David Duren, went to the electric chair in 2000, having dropped his appeals after a religious conversion.

Jaffe called Kinder’s resentencing “excruciating” and “heart-wrenching.” It featured testimony from Bedsole’s boyfriend, who survived his wounds that night. But guards and teachers at the prison where Kinder has been locked up testified that he has been a model prisoner. His disciplinary record includes only one infraction, and he earned a high school equivalency diploma, an associate’s degree from a community college and a trade school diploma in furniture refinishing.

In addition, Duren’s attorney signed an affidavit recounting that his client had said he made the decision to shoot Bledsoe and her boyfriend without telling Kinder, and that Kinder had told him there “was no need to shoot.” Jaffe said Circuit Judge Teresa Pulliam found Kinder “was not only rehabilitatable, but had been rehabilitated.”

Pulliam has scheduled several other hearings for inmates convicted in Jefferson County, the state’s largest, said Michael Hanle, president of the Alabama Criminal Defense Lawyers Association. But for convicts in other counties, there’s little movement, he said.

“We’re not quick to the table,” said Hanle, who is also Jaffe’s law partner. Rural counties especially “are not moving as quickly as in some other jurisdictions, and they’re having a little more difficult time.”

Many judges aren’t eager to reduce sentences, and defense lawyers are often court-appointed and lack the resources to assemble their case. But the biggest obstacle is time, he said.

“Some of these guys have been in prison 20, 25, 30, 35 years, and a lot has happened during that time,” Hanle said. Finding witnesses becomes harder, and it’s more difficult to present testimony that would point toward a lighter term.

“And of course, a defendant has a lifetime literally in the Department of Corrections, which comes with its ups and downs,” he said. “Some of them have gone on to do great things as far as their education, training and rehabilitation. Others have had problems, and all those things are going to be brought back up during the resentencing.”

Hill said the judges he knows “all want to follow the law, whether they like it or don’t like it.”

“I think it’s a necessity that we do it,” he added. “It’s one of those things that when you see what the situation is, you need to address it. It took us a couple of years to address it, but we did, and I’m very glad that we did.”

Miller is represented by the Montgomery-based Equal Justice Initiative, which took his case to the U.S. Supreme Court. Bryan Stevenson, EJI’s executive director, did not respond to a request for comment.

Nationwide, about 2,500 inmates are eligible for new hearings under the Miller and Montgomery decisions. It’s not clear how many of them have had those hearings, but states well beyond Alabama have been slow to schedule them, said Josh Rovner, a juvenile justice advocacy associate at The Sentencing Project.

“While there are certainly states that have sharp declines — sometimes because state supreme courts required it — in many cases, the states barely budged in the number of people serving life without parole for things they did as a juvenile,” Rovner said.

For example, Iowa has moved quickly to resentence inmates eligible for new hearings under Miller, and it has eliminated mandatory minimum sentences for crimes committed by juveniles altogether, Rovner said. But in Arkansas, a judge recently struck down the state’s new sentencing law because it failed to provide for individualized hearings. And the three states with the most juvenile life-without-parole sentences — Michigan, Louisiana and Pennsylvania — “really dragged their feet on this,” he said.

“The facts are rarely in question,” Rovner said. “The question is what is the juvenile’s maturity, involvement in the offense, what was his family life like — these are questions that are able to be answered.” Caseloads and procedures might move at different paces in some places, but he said waiting five years since the Miller decision “is preposterous.”

Hello. We have a small favor to ask. Advertising revenues across the media are falling fast. You can see why we need to ask for your help. Our independent journalism on the juvenile justice system takes a lot of time, money and hard work to produce. But we believe it’s crucial — and we think you agree.

If everyone who reads our reporting helps to pay for it, our future would be much more secure. Every bit helps.

Thanks for listening.

The state of Iowa has not resentenced their JLWOP inmates, the governor commuted their sentences to a sentence which still equals a life sentence before they are eligible for parole. What happened to being able to have their resentenciing hearing and the fact that the sentences are supposed to allow them the opportunity at parole to have a chance at life, not when they are in their 70’s or 80’s?

I have been reading many of your stories and all of them are sad, the only

Thing that I have to say that those long sentence are not helping any thing and of course if those inmates would have rich parent they would not spent those long sentence or no sentence at all. And the same thing goes for for the state of GEORGIA nothing has been done for juveniles w. a Life sentance – my son came into the system with 16 yes old he served 25 years and he is still in! LIFE has been a challenge his father passed and I am 67 yes old will I see him outside of prison I don’t know .!!!