A wide-ranging study of youth incarceration in California outlines what it calls the debilitating effects on the health of teens, their families and society when youthful offenders are tried and sentenced as adults.

“Juvenile Injustice,” from Human Impact Partners, concludes that laws designed to try youth in adult courts not only fail to curtail recidivism but are so inherently flawed and biased that the entire approach must be scrapped. Researchers found that youth tried in adult courts are sentenced to prison twice as often as people 18 to 24 charged with similar offenses in adult court. Eighty-eight percent of all California juveniles tried as adults were people of color.

Youth in adult prison are more likely to contract communicable diseases, suffer chronic disease, have serious oral health problems and are more likely to be assaulted. Youth in an adult facility are 36 times as likely to commit suicide than youth held in juvenile facilities, the report said.

“Youth in adult prison are twice as likely to be beaten by staff and 50 percent more likely to be attacked with a weapon than youth in juvenile facilities,” the report said. They also experience severe trauma and stress that can damage their still-developing minds. Rather than deter crime, treating children as adults make them more likely to reoffend, damaging their families and communities, it concluded.

Authors of the report, a collaboration among several community groups, juvenile justice advocates and law experts, held focus groups in Los Angeles, Oakland and Stockton of family members of juveniles tried as adults, juveniles tried in both adult and youth courts, and community organizers who work with youth. They also interviewed public defenders, probation officers, a youth mental health expert and a literacy specialist who works with youth in a probation camp.

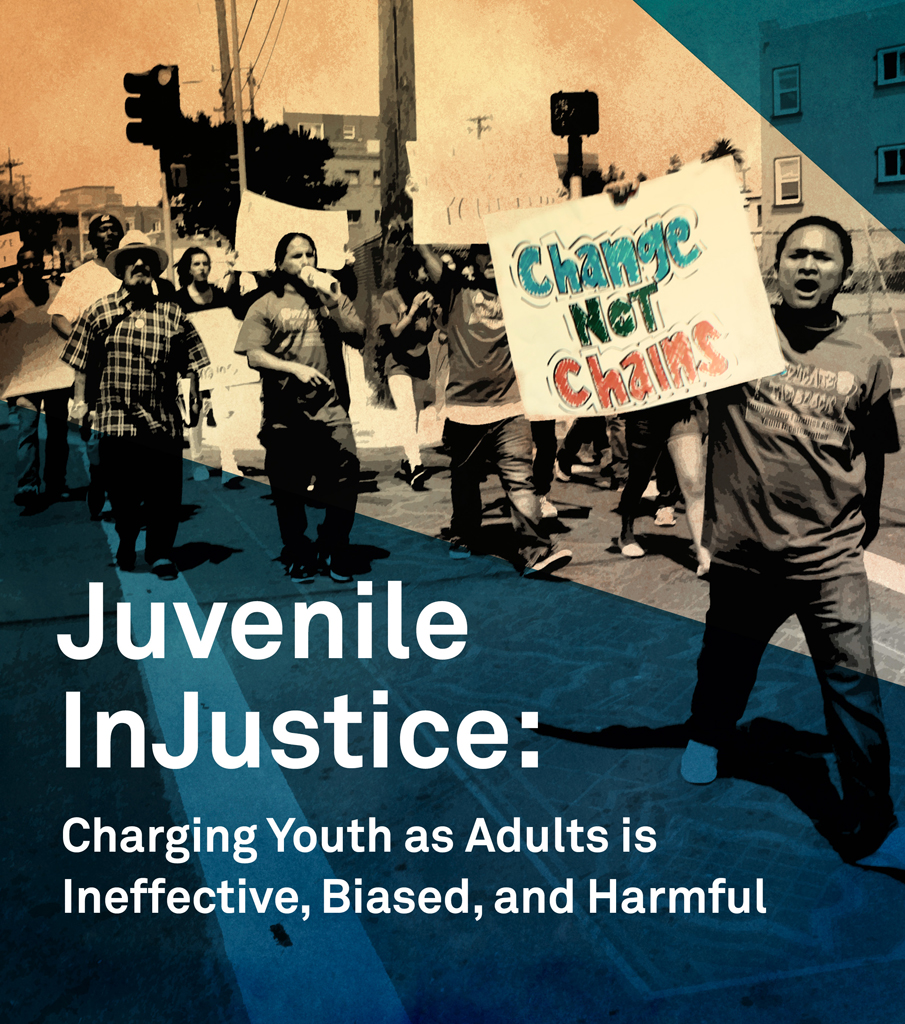

California Alliance for Youth and Community Justice

Homies 4 Justice interns rally with the Justice Reinvestment Coalition in Alameda County, summer of 2016. Homies 4 Justice is an internship program run by Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice out of Oakland, CA.

“Family members ... discussed how their loved one’s arrest, trial, and incarceration has negatively impacted their health and wellbeing,” the report said. “When Luisa’s 14-year-old son was charged as an adult, the stress and grief were overwhelming.”

She couldn’t eat, lost 33 pounds in one month and lost her job. Other family members said they had trouble eating or getting out of bed in the morning or developed high blood pressure, the study found.

The groups also talked about the conditions that led the teens to commit crimes. Poverty, physical or sexual abuse and emotional neglect were common, as was having a family where domestic violence, household drug abuse and incarceration of other family members was typical.

All those stresses put teens in jeopardy that is compounded when they are put in the adult justice system, the report said.

“The numbers of problems we found are so overwhelming, and represent so many challenges we are facing,” said Ana Tellez, one of the study’s authors and communications director for Human Impact Partners. “We really need to dismantle the system as it is set up today.”

The report offered several potential solutions, the first being to “eliminate the practice of charging youth as adults under any circumstances.”

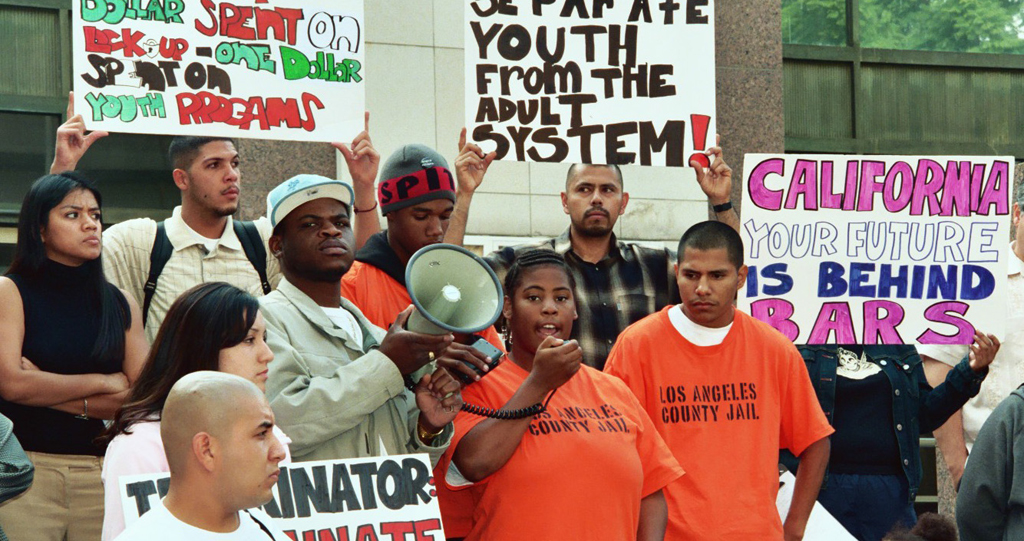

California Alliance for Youth and Community Justice

Youth Justice Coalition members rally in Los Angeles County.

It also recommended better training for staff working at all stages of the prison and juvenile justice systems, saying formerly incarcerated people and local community organizations should be part of the training. It also urged more research and pilot projects to find alternative solutions to best deal with youth who commit serious crimes.

Human Impact and partner groups for the report, including Youth Justice Coalition and Communities United for Restorative Youth Justice (CURYJ), said they have been bolstered by the recent voter approval of Proposition 57, which reverses a three-decade law — enacted by Proposition 21 during a tough on crime phase — that made it much easier to try teens as adults.

The new law calls for judges, not prosecutors, to make decisions on when to charge juveniles as adults and changes the criteria used to make those decisions.

Mar Vallez, organizing and policy campaign manager of CURYJ, said advocates need to capitalize on the momentum of Proposition 57 and changing sentiments to make lasting changes.

“That sent a pretty loud message that Californians are waking up to the problem of sending youth to adult prisons,” Vallez said. “I think we are starting to see a push, not only from judges and attorneys, but also our legislature, to move from punitive, draconian measures to healing and actually fixing problems.”

California Alliance for Youth and Community Justice

Youth Justice Coalition members rally as part of the "March for Respect" in Los Angeles County, 2003.

The study focused solely on the juvenile justice system in California, where a 2000 voter initiative created some of the nation’s harshest penalties for youth, and where a 2016 initiative began tipping the pendulum back toward the center. As the nation’s largest system, and often at the forefront of reform, the state is among the most watched by juvenile justice advocates.

Juvenile justice advocates are seeing signs that California is not alone.

“We’ve seen the numbers of incarcerated youth across the country decrease in recent years,” said Naomi Smoot, executive director of the Coalition for Juvenile Justice in Washington, D.C.

“I think there is definitely more awareness, especially here on Capitol Hill, of the benefits to children by getting away from incarceration,” she said. “But there are also the fiscal realities. It costs more to incarcerate children, and I think that may also speed up the changes. … we see financial and social savings when children are put into community-based placement.”