“I wasn’t as bad as they say I was,” said disgraced former Juvenile Court Judge Mark Ciavarella, on his public perception in the wake of the Kids for Cash scandal.

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

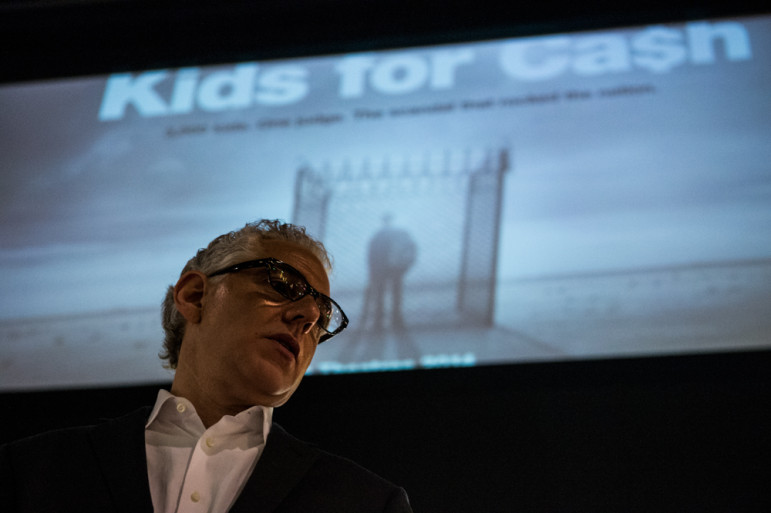

Director Robert May at the premiere of his film "Kids for Cash " in Wilkes-Barre, Pa.

WILKES-BARRE, Pa. — After a few beers one evening in the mid-1960s, Mark Ciavarella, in high school at the time and applying the kind of inexplicable logic that experts say is typical of many teens whose brains have not fully developed, conspired to steal a car and go for a joyride with his cousin and a friend. A detective noticed the teenagers suspiciously lingering around the car and pulled over. Ciavarella’s friend and his cousin darted away, but Ciavarella was not so lucky. The detective nabbed him and threw him in the back of his police car.

The officer’s decision would determine the young Ciavarella’s future. Would he arrest and process the suspect, possibly derailing the young man’s promising future? A staggering number of young people who end up in the criminal justice system are more likely to end up in prison than they are to earn a college degree.

The officer’s decision would determine the young Ciavarella’s future. Would he arrest and process the suspect, possibly derailing the young man’s promising future? A staggering number of young people who end up in the criminal justice system are more likely to end up in prison than they are to earn a college degree.

During the ride, Ciavarella’s heart pounded. Instead of placing the young Ciavarella into the relentless teeth of the juvenile justice system he gave the young man a break and took him home. He was greeted by his hysterical mother screaming, “I can’t believe my son is a criminal!” His father’s feelings were equally clear; he reared back and punched his son in the face.

“Knocks me out cold,” Ciavarella says.

“I didn’t need the system to take care of my problems,” Ciavarella continues. “My parents took care of my problems.”

The tough love, however, did not work. Ciavarella, now a disgraced judge whose name is synonymous with one of the biggest judicial scandals in recent memory, will in all likelihood die behind bars. Ciavarella was a lifelong resident of Wilkes-Barre. Now, he is imprisoned in a federal penitentiary, inmate number 15008-067, more than a thousand miles away from his grandchildren. They will learn about their grandfather from the hundreds of news clippings that detail his breathtaking corruption, and in the movie about his exploits that he agreed to star in.

The Plot

Ciavarella tells this story in a series of riveting interviews -- conducted without the judge’s attorney’s knowledge -- in a new documentary directed by Robert May, called “Kids for Cash,” named after the scandal that dominated headlines, airwaves and dinner table conversations in this industrial town of roughly 40,000, the county seat of Luzerne County, near the Pocono Mountains in Northeastern Pennsylvania.

Click here to see more photos of the "Kids for Cash" scandal.

“It’s the story behind the story,” May said of “Kids for Cash,” which opens nationwide at the end of the month.

Ciavarella is doing time for his involvement in what prosecutors say was an elaborate kickback scheme for accepting what Ciavarella called “finder's fees” from Robert Mericle, head of the largest developer in Wilkes-Barre, which built two for-profit juvenile centers to replace the crumbling county-run facility.

Ciavarella proudly ran on a platform of zero tolerance in the mid 1990s. He ran ads during election season that promised he would teach children how to listen to rules if parents couldn’t. He kept a busy schedule on the lecture tour circuit, telling anyone who would listen that he would throw children in prison if given the chance. His message reflected what many experts say was the dominant one from law enforcement in the wake of the shootings in Columbine.

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

Outside the abandoned Luzerne County Juvenile Detention Center in Wilkes-Barre, Pa., which once housed detainees of convicted judge Mark Ciavarella.

Ciavarella would put a child behind bars for an infraction as minor as cursing at an adult or having a slap fight in gym class. But here he was reminiscing to May about his time as a teenager, ready to commit a felony stealing a car, and given a break by a police officer.

He grew up to become a juvenile court judge who aped the ultra-strict worldview of his father and ended up convicted on a laundry list of federal charges, facing nearly three decades in prison.

May, the Academy Award-winning producer of Errol Morris’s “Fog of War,” tried to point out the mindbending hypocrisy that Ciavarella displayed in recounting that story.

“He missed the irony of it all entirely,” May said as he talked about his latest movie in a Midtown film company office in New York City. “I literally tried to point out the irony on display there. He couldn’t see it that way. I think he was raised by strict parents. He took his father’s word like it came directly from God, and that’s what the judge’s belief system was. His kids said as they grew up, that’s how they described him, that’s what he was -- a zero-tolerance father.”

May, who lives in Luzerne County with his wife and teenage son, 17, and daughter, 14, spent as many as 16 hours a day interviewing the subjects in the film. His aim was to tell the whole story, not just make an issues-oriented film that preached to the choir, he said. He would have abandoned the project if he could not secure the “villain’s side of the story,” as he described it -- Judge Ciavarella and his accomplice, and once close friend, in the “Kids for Cash” scandal, Judge Michael Conahan.

“No one would ever look at the whole picture,” Ciavarella says. “They only wanted to look at a little bit of the picture.”

On some occasions, he would spend eight hours with a child who was thrown into a detention facility by Ciavarella, and for the next eight hours, he would spend in intimate conversation with the judge who put the child there.

May’s “Kids for Cash” is not a polemic. It is filled with facts and figures that advocates and experts are all too familiar with, but they are not what drives the film’s tense, gripping narrative. It is the specific details of the characters’ stories from all sides of the scandal -- including the judge, the children and their families, scandal-hungry residents, and the diligent reporters who helped break the scandal wide open -- that make it so engrossing.

His film explores the emotional inner-lives of all the characters whose lives were swept up in the controversy, most intriguingly former judge Ciavarella, who many locals here look at as evil personified.

The Villain

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

Wilkes-Barre, Pa., where hundreds of teens were remanded to private juvenile facilities in Luzerne County by Judge Mark Ciavarella in what has come to be known as the "Kids for Cash " scandal.

The residents of the towns in Luzerne County had their first opportunity to hear their hometown villain, Ciavarella, for themselves when May screened the movie last Thursday night at the RC Theatres in the heart of downtown Wilkes-Barre. When Ciavarella became a Juvenile Court judge in Luzerne County he promised to mete out the kind of punishment that informed him as a child. If the parents of Wilkes-Barre could not raise their children then he would.

Whether in a genuine attempt to relate his story, which he feels has been twisted by a vulturish media, or an act of pathological narcissism, Ciavarella agreed to secretly meet with May and his producer Lauren Timmons and answer questions about the scandal.

“I have not told my attorney that I agreed to do this documentary, and maybe me doing what I’m doing is going to come back to hurt me,” Ciavarella says in the film. “But I felt this was an opportunity for me to let people know what really happened. I’m not this mad judge who was just throwing kids away and shipping them out and locking them up putting them in shackles.”

May does not use voiceovers in the film. He said it was both a storytelling decision and a journalistic one. He wanted his movie to feel more like a tense thriller instead of a gussied-up newsy docudrama. But he also wanted to put the onus on the audience. He wanted them to draw their own conclusions about Ciavarella.

Ciavarella insists in one interview that he did not take a “penny” to throw children in detention center cells. And it’s in that comment that May tips his hand a bit as to where he comes down in the controversy. He seems to be saying the judge didn’t need money to throw children in prison. He was happy to do it for free.

“The way Ciavarella ran the courtroom,” said one defense attorney interviewed in the film, “you could have had F. Lee Bailey there and the kids were going to go away.”

The Hero

The money and the implication of quid pro quo and corruption around investors, land developers and money laundering brought attention to what advocates and experts say was the real scandal that was happening in plain sight. Ciavarella, emboldened by the trendy policy initiative coined “zero-tolerance,” used his position of power to throw an estimated 3,000 children into juvenile detention centers, many of them for minor offenses.

More troubling, say experts such as Marsha Levick, is that this all happened in open court in front of prosecutors, public defenders, and other members of the court. Instead of stepping in to stop it, they let it go on, while child after child was taken from their families and thrown into detention facilities like something out of an absurdist nightmare.

“I think there's a coziness that happens in courtrooms, particularly in small towns with the same lawyers coming before the same judge over and over again,” she said. “It’s a cocoon of silence; it’s a go-along-to-get-along situation. No one wants to challenge the judge.”

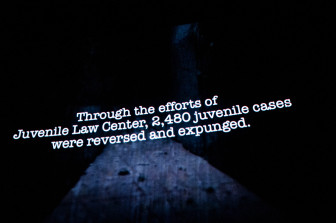

If Ciavarella is the villain in this narrative, then Levick is one of the heroes, Deputy Director and Chief Counsel of the Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia. She helped bring to light Ciavarella’s draconian system of incarcerating children for minor offenses with no legal representation. She helped get his first victim -- Hillary Transue, who Ciavarella put away for making a satirical MySpace page about a vice principal -- out of the county-run juvenile detention center after she learned that the judge had denied her an attorney. The Juvenile Law Center reversed and expunged 2,480 of Ciavarella’s convictions.

Echoing one of May’s themes running through the film, Levick said the real scandal was how cavalierly and routinely Ciavarella violated thousands of young defendants' rights.

“We can hear the $2.9 million figure and most people think, ‘That’s unbelievable, that’s not happening here,” she said. “I think in Luzerne County you had this internal conspiracy of silence. There were professionals in the courtroom every day -- lawyers, probation officers, court officers, public defenders -- who could see every day the parade of constitutional violations that were going on in front of them.”

And the application of zero-tolerance fueled policies is not limited to the imprisoned disgraced judges of Luzerne County, Levick said.

“The day-to-day violations of the kids’ rights do go on all over the country,” she said. “The dynamics that were present in Luzerne County are present elsewhere.”

The Director

May says he is no longer any good at parties. The making of the film, which he started to film as the scandal was unfolding in real-time in April of 2009, has transformed him. He cannot participate in a conversation without him dredging up some statistics about the pittance society spends to educate children versus how much it splurges to incarcerate them, or rattling on about the “school-to-prison pipeline."

“I’m serious about this,” he said. “I literally can’t stop talking about it.”

Even his children, he said, have gotten impatient with his newfound passion. After he recently scolded his son for some minor infraction, his son shot back: “It’s like you told me, Dad: my brain isn’t fully developed yet!”

May said he thinks his “ah-ha” moment in shooting the film is when he started interviewing Charlie Balasavage, who was sent away by Ciavarella for possessing a stolen scooter. Balasavage wanted to go to school, May said, but he was scared to go because of the ridicule he endured for having a speech impediment.

“Ciavarella thought he knew all he needed to know about Charlie after he flipped through some documents,” May said. “But he didn’t know him. And that goes for this whole system of zero-tolerance. They don’t know anything about these kids.”

For many Luzerne County residents who attended Thursday night’s screening, watching the children describe in exquisite detail the fallout from Ciavarella’s abuse generated strong emotion. Viewers in Auditorium 7 gasped and expressed outrage in hushed tones as the movie delved into the stories.

There was not an audience in the nation who was more familiar with the details May chronicles in “Kids for Cash.” And yet it still stoked an irrepressible sense of rage in the audience similar to the incredulous reaction upon reading "The Count of Monte Cristo" -- if you reimagine Edmond Dantes as a chubby, babyfaced child with a speech impediment.

And May said that’s the point. He said the gasps of shock in the theater did not surprise him. As much as people thought they knew about the scandal, they didn’t know its human scale until they could hear those horror stories in the voices of the people who were affected by the judicial abuse that played out in the juvenile court.

Some of them in ways that could not be undone.

The Victims

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

Sandy Fonzo, the mother of Edward Kenzakowski who was remanded to a private juvenile detention center by judge Mark Ciavarella in the "Kids for Cash" scandal, at the premiere of Robert May's film.

After the viewing, some of the children and parents featured in the film joined a catered after-party, with tables covered in black and white tablecloths decorated with flickering candles. A massive “Kids for Cash” poster of a child in a cage ringed with razor wire stood yards away from a display of Lego characters. A neon yellow sign announced the “Snack Bar” in the movie theater lobby. The concession stand was closed, but beneath the glass, the candy display was filled with a dazzling array of confections, and set on the counter a sign advertised a tub of buttery popcorn and free refills.

Above the carefree innocence associated with movie theater treats was a screen mechanically scrolling through grim statistics about the juvenile justice system.

If someone would have asked Sandy Fonzo what she thought about the juvenile justice system, criminal justice reform, and zero tolerance she would have shrugged and looked back blankly at the questioner.

“I didn’t know anything,” she said. “I was absolutely unaware.”

She never considered herself a political person.

“But now I do,” she said.

When May screened the film for her for the first time, Fonzo learned that Ciavarella was also in it. Initially, she said, it felt like “a slap in the face.” But she eventually came to understand that the movie needed balance, and more importantly, insight into their decision-making so hopefully what happened to her son wouldn’t happen to other children.

In the film, Fonzo explains how her son, Ed Konzakoski, ended up in front of Ciavarella in a misguided attempt by her son’s father to scare him straight.

“He went in there a free-spirited kid,” she says, “and he came out a hardened man.”

Konzakowski shot himself in the heart after years of wallowing in a system he was placed in by Ciavarella.

“I don’t think I’ll ever have to see this movie ever again,” she said.

Fonzo has dedicated her life to reforming the system that she blames for taking her son’s life. She runs a blog called Prison 4 Profit. Her business card has the words “Seeking the End of Modern Slavery” written on it in italics. She has lost her innocence, she says, and can no longer go back to the days when she had the luxury of not knowing what was happening on election day.

“I’d never been to court,” she said. “I thought these were professionals, these are people who have the kids’ best interests at heart. They were going to fix things. I was naive. I trusted them. I don’t know that I’ll ever trust anyone ever again.”

Hillary Transue, now 22 and studying creative writing at a graduate program at nearby Wilkes University, said she is happy May’s film has given her and the other victims of Ciavarella’s zero-tolerance policies a voice.

“That’s what has the power to make change,” she said.

She said she is used to talking about the inequities of the juvenile justice system.

“I’ve sort of been in this role as a victim and advocate since I was 15 years old,” she said.

She said that even before she was hauled in front of Ciavarella, there was a palpable sense in her community that teenagers and children were looked at warily.

“We didn’t have the words for it then, zero-tolerance, but there was always the sense in our community that we were not trusted by adults. After a while, you get to the point where you don’t trust adults.”

Judy Lorah, an aunt to Amanda Lorah who was put into a detention center by Ciavarella for a fight during a volleyball game, smiled as she chatted with other members of the audience during the reception after the show. As the scandal unfolded, she brought a document to educational administrators showing a list of 153 children from Amanda’s school who Ciavarella had put behind bars.

“I’m proud of the movie, the kids’ story needed to be told,” she said. “I think it’s started the healing process. For all these years we’ve only heard the judges stories. They never really told what happened to the children, how it affected their lives, how it affected their family's lives.”

Amanda’s father did not have time to talk. He had to rush to the hospital. After Amanda had taken some promotional pictures she had been rushed off to the hospital. She had gone into labor. She was going to give birth to her first child.

The Set

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

Downtown Wilkes-Barre, Pa., on the morning of the premiere of Robert May's film "Kids for Cash," A statue of a child stands in the foreground of the infamous courthouse.

Our Lady of Fatima Blessed Grotto is a clumsy jumble of religious iconography on North Street on the outskirts of downtown set in a horseshoe-shaped space blasted out of a rocky hillside. Among the votive candles, cherubic winged angels, and carved beatific lambs, there is a white statue of a child kneeling in supplication before a flesh-colored Jesus mounted on a low cliff where a visitor can take in the grandeur of the courthouse.

When it was built in the early 20th Century, the Luzerne County Courthouse was intended to be a soaring tribute to the success of Wilkes-Barre as a burgeoning powerhouse in the tri-state area, a monument to public pride. There are few streets in Wilkes-Barre where residents or visitors do not have a clear view of the majestic courthouse, which sits on South Main Street along the banks of the Susquehanna River. It is a towering beaux-art bulwark with an opulent marble dome buttressed by a series of elegant arches that towers above the mom-and-pop shops, university buildings, and well-kept middle-class homes that make up the town.

But now, with two of its once most respected judges in prison in the wake of the scandal, for too many residents the majestic building is a reproach, a troubling reminder of what happens when absolute power goes unchecked, and how it can determine the fates of its most vulnerable citizens.

Just blocks away from the courthouse, looming on a hill, sits the shuttered county-run juvenile facility, closed to make way for the private detention centers at the heart of the scandal. It is where Ciavarella sent his first batch of zero-tolerance offenders. Approaching it at night beneath a full moon the padlocked mansion-like structure feels like an eerie set piece from a horror movie.

The new facility built, named PA Child Care, is difficult to find. It doesn’t show up on Mericle’s website along with their other properties. It’s four miles away from the courthouse and there are no signs leading visitors to it. It sits at the bottom of a lonely hill sandwiched between the train tracks and Grimes Industrial Park, also built by the same developer charged with paying off the judges. The building looks like it could fit in unobtrusively at a local office park.

“We lived in our own little bubble, all of us, living out our own little lives,” Fonzo said, a picture of her and her dead son engraved on a silver heart that hangs from her neck. “We weren’t aware of any troubles in our town. But now I am. And it’s a scary world out there.”

Pingback: The Kids for Cash Scandal | Bokeh