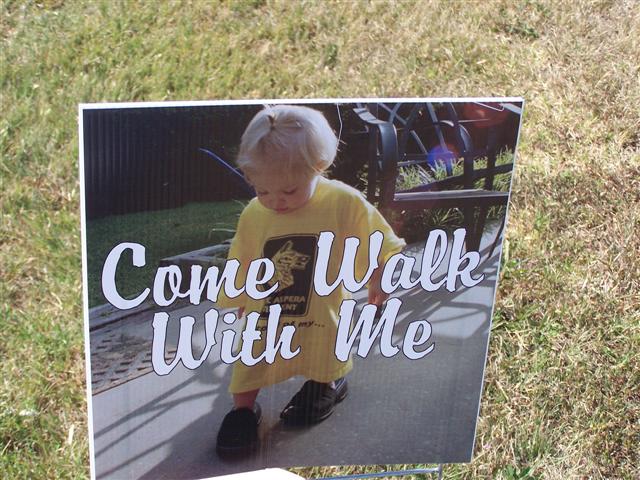

Kelsey Smith-Briggs, 2, suffered a host of injuries before dying from a blow to her stomach while in the care of her mother and stepfather. She had been receiving regular visits from Oklahoma child welfare workers. Kelsey became a sort of "poster child" for Children's Rights' work in Oklahoma. Photo courtesy of whokilledkelsey.com

More than four-years after Children’s Rights, a New York-based non-profit, filed a law suit on behalf of nine children in Oklahoma, a settlement has been reached that will bring changes to the state’s child welfare system.

On Wednesday, U.S. District Judge Gregory Frizzell approved the settlement reached between Children’s Rights and Oklahoma’s Department of Human Services in January.

“There just has not been the funding to hit some of these critical needs,” Sheree Powell, communications coordinator for the state’s Department of Human Services, said. “We don’t control the purse strings, but it was understood in federal court that we’ll make good-faith efforts to improve everything within our control.”

Under the agreement, “specific strategies to improve the child welfare system” as it relates to 15 performance areas will be outlined, detailed and put into practice over the next four years.

“We’re confident the settlement will result in better services and protection than foster children [in Oklahoma] currently receive,” said Marcia Robinson Lowry, Founder and Executive Director of Children’s Rights.

The Oklahoma effort is not the first time the New York-based group has spearheaded such an effort. In fact, since 1995, Children’s Rights has launched legal challenges in at least 15 states around the country, seeking improvements in child welfare systems – all but two of which have proven successful.

Marcia Robinson Lowry, Executive Director at Children's Rights. Photo courtesy of Children's Rights.

The advocacy group currently has 11 active cases in different states. Legal battles are ongoing in Massachusetts, Rhode Island and Texas. Eight other states and Washington D.C. are in the process of implementing reform plans developed by the group and approved by federal courts.

Oklahoma is the first of these states to reach a settlement without a federal decree, meaning progress will be tracked by independent monitors and not by federal officials.

Yet, this is one of the most far-reaching settlements Children’s Rights has ever entered into, Lowry said. While not federal officials, monitors retain the authority to file complaints in federal court if the DHS fails to make good-faith efforts in instituting improvements

“In many settlement agreements there are specific things required,” Lowry said, adding that there is no limit to what the monitors can require the state to include in the plan. “This settlement gives monitors very broad authority over what they can require the agency to do to comply with the order and that authority can by enforced by the federal court.”

Implementing systematic change and comprehensive reform plans is no easy task. The path is often long and complicated, stretching over a period of years, with a number of systems experiencing setbacks along the way – Georgia included.

After more than seven years, Georgia still struggles to meet federal benchmarks.

The finalization of Oklahoma’s settlement comes on the heels of Metro Atlanta’s completion of foster care legal representation requirements stemming from a 2005 lawsuit between Children’s Rights and Georgia state officials. However, work to improve Metro Atlanta’s child welfare sy stem – stemming from a separate suit brought on by Children’s Rights in 2002 – is ongoing.

“When we brought the legal challenge to Georgia in 2002 it was one of the most dangerous foster care systems we had ever seen,” said Ira Lustbader, Associate Director with Children’s Rights. “There was no reasonable oversight for these kids and the outcomes were just horrible.”

Two of the three legal challenges Children’s Rights filed between 2002 and 2005 looked specifically at legal representation for foster youth in Fulton and DeKalb counties (Metro Atlanta), and a federal monitor was assigned to each county following a right-to-counsel settlement in 2006.

Having shown dramatic improvements in legal representation for foster youth, DeKalb County was released from federal oversight in 2008.

During the same period, Fulton County managed to reduce caseloads for juvenile attorneys and established an independent Child Advocate Attorney’s Office, but fell short of meeting the required benchmarks until late 2011. Fulton was released from federal oversight in December of that same year, with the backing of Children’s Rights, after making and maintaining numerous improvements.

The third suit, filed against state officials but still focused on the child welfare system in Metro Atlanta, sought comprehensive reforms in 31 different areas and is still under the oversight of federal monitors.

“In some areas the progress has been very good, but there are still substantial improvements needed in other areas,” Lustbader said. “For example, kids are still not getting required medical, dental and mental health check-ups.”

While the state has made strides in delivering these services to children in foster care, Georgia’s Division of Family and Children Services (DFCS) has not been able to provide them at a level that meets the 2005 settlement agreement.

A recent joint investigation by the Atlanta Journal-Constitution (AJC) and Channel 2 Action News discovered an increase in child deaths that had been in contact with DFCS within the last five years. Thirty-five children with such history died in a 10-week period between Dec. 1, 2011 and Feb. 12, 2012, roughly 40 percent of the annual average.

Four of the deaths were instances of abuse, and 10 due to medical problems, DFCS told the AJC. Investigating instances of abuse or neglect and the timely delivery of medical check ups for foster youth are areas of the settlement DFCS continues to struggle to meet, according to the latest monitoring report.

Ravae Graham, Deputy Director of Legislative Affairs and Communications for Georgia's Department of Human Services, said the DHS "will not speculate" about the deaths.

A number of factors effect reforms

Budgetary constraints, staff turnover and an influx in children entering the foster care system can place added burdens on systematic reform.

Oklahoma’s recently retired head of DHS served in his post for 14 years, yet Georgia and other states have seen a considerably high rate of turn over among top brass. Clyde Reese, Georgia’s current Commissioner of the DHS, has held the post for less than 18 months.

Shortly after Children’s Rights brought legal challenges to Georgia in 2002, both the GADHS Commissioner and the Director of DFCS, the state agency charged with investigating child abuse and neglect, resigned following deaths of children in the foster care system.

“We’ve found Commissioner Reese very willing to discuss the agencies progress and remaining challenges,” Lustbader said. “ He has held himself accountable for implementing these reforms.”

Also in Georgia, specifically Metro Atlanta, there has been an influx of children entering the foster care system, roughly a 55 percent increase in the first six months of 2011 compared with the pervious six-month period, according to the latest monitoring report.

Some advocates worry the increased workload could potentially overwhelm caseworkers, hampering their ability to make decisions in the best interest of the children they serve. According to the most recent monitoring report, however, caseloads throughout Georgia continue to be universally low.

Back in Oklahoma, the work has just begun.

The state’s Department of Human Services (OKDHS) – working in conjunction with state legislators, the governor’s office, stakeholders and independent monitors tasked with tracking the state’s progress -- has until March 30 to present a formal plan for making the changes a reality.

“We are committed to the safety and well-being of the children we serve,” Oklahoma Department of Human Services Director Howard Hendrick said in a release. “The strengths in our system allowed us to reach this agreement and our commitment to children extends far beyond the terms of this agreement."

Recently retired OKDHS Director Howard Hendrick. Photo courtesy of OKDHS.

Designated the Oklahoma Pinnacle Project, DHS officials have already taken a number of steps to start developing the improvement plan. The department recently convened a statewide summit with DHS child welfare staff to identify areas of need and solicit recommendations for improvements.

“We’ve made a lot of strides in the last few years,” Powell said, citing nearly a quarter decrease in the number of children in state foster care, at least in part due to increased adoptions and placement of foster youth with family or relatives.

Oklahoma has the highest adoption rate per capita in the country, Powell said. Roughly 8,000 kids are currently in the foster care system, down from more than 11,000 in 2008.

Three independent monitors, known as co-neutrals, will oversee the progress throughout the duration of the improvements, filing regular reports on the progress of OKDHS in key performance areas.

You can follow the progress at http://www.okdhs.org/programsandservices/foster/cwp/.

Children’s Rights shows no signs of slowing down.

In addition to Children’s Rights 11 active cases, six states and districts have completed court-order improvement plans successfully – including Kansas, New York City and New Mexico.

“These cases require a lot of resources. We are obligated to prove the facts that children are being harmed,” Lowry said, explaining that often means expert testimony, public documents and open record requests, along with a considerable investment in staff resources.

“This is solely about fixing the system for children going forward,” she said.

Children’s Rights generally invests eight to 12 months of research before ever filing a legal challenge in a state, and with good reason. The firm doesn’t seek monetary damages, only the reimbursement of legal expenses. Under federal law, state’s can be required to refund negotiated legal dues only if the suit is successful.

“I think these cases are real examples that our civil rights’ laws are still there and how they can be used to protect our children,” Lustbader said.

Lowery said the firm is currently researching and investigating a number of other states, but declined to go into detail until after a final decision is made on whether to pursue legal action.