Gail Wasserman and her colleagues from the Center for the Promotion of Mental Health in Juvenile Justice at Columbia University published an important new study that was released mid-February in Criminal Justice and Behavior: "Psychiatric Disorder, Comorbidity, and Suicidal Behavior in Juvenile Justice Youth." It may be the best source of information yet on the prevalence of substance abuse and mental health disorders among youth in the juvenile justice system.

Gail Wasserman and her colleagues from the Center for the Promotion of Mental Health in Juvenile Justice at Columbia University published an important new study that was released mid-February in Criminal Justice and Behavior: "Psychiatric Disorder, Comorbidity, and Suicidal Behavior in Juvenile Justice Youth." It may be the best source of information yet on the prevalence of substance abuse and mental health disorders among youth in the juvenile justice system.

We need accurate information. I've heard many practitioners around the country make the same mistake, claiming that "70 percent" of the youth in "the system" have diagnosable disorders. As I've said before elsewhere, this common mistake usually starts with a misreading of the 2002 study by Linda Teplin at Northwestern University.

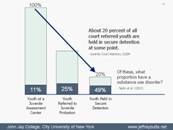

Teplin and her colleagues found high rates of substance abuse and mental disorders among a population of juvenile offenders, but many readers failed to note that the study was about just one large detention center — not exactly a good proxy for the entire juvenile system. The Teplin study did not include data about youth at other stages of the juvenile justice process, such as probation and intake.

Gail Wasserman and her colleagues, on the other hand, used a high-quality and consistent methodology (the DISC) to measure the presence of disorders among nearly 10,000 juveniles in more than 50 jurisdictions and at varying points of juvenile justice contact, including juvenile intake.

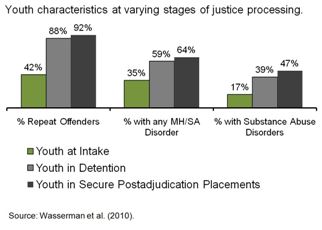

When you look at their findings it is clear that mental health and substance abuse issues are not the main reasons youth come into contact with the justice system, but both problems increase in prevalence as youth are processed more deeply into the system.

In other words, as we look more deeply into the juvenile justice system, from youth at intake to those in detention and those in long-term confinement, we begin to see far more juveniles with prior offenses and more youth with substance abuse and mental health issues.

This is probably because youth with more serious problems tend to accumulate (i.e., they are less likely to be diverted) as delinquency cases are processed by police, courts, and correctional agencies. By the time we are dealing with multiple-offense youth in a secure setting, those with mental health issues/substance use disorders are much more common, even making up the majority of the population.

I wrote to Dr. Wasserman and asked her if this was a fair interpretation of her research, and she replied, "Yes. That is it. Healthier kids may not enter [the system], or if they do enter they may take better advantage of opportunities for intervention."

Comparing this new study with previous research, we can also see that mental health and substance abuse prevalence rates among youth at juvenile justice intake are indeed higher than among youth in the general population (35 percent versus 20 percent for mental health; and 17 percent versus 8 percent for substance abuse -- see my PowerPoint presentation, "Positive Youth Development: From Theory to Practice" for a visual summary of past research), but even this comparison is misleading. If the general population figures were adjusted for socioeconomic status, the differences would likely be smaller.

Comparing this new study with previous research, we can also see that mental health and substance abuse prevalence rates among youth at juvenile justice intake are indeed higher than among youth in the general population (35 percent versus 20 percent for mental health; and 17 percent versus 8 percent for substance abuse -- see my PowerPoint presentation, "Positive Youth Development: From Theory to Practice" for a visual summary of past research), but even this comparison is misleading. If the general population figures were adjusted for socioeconomic status, the differences would likely be smaller.

If researchers measured the rate of substance abuse and mental health problems among only poor and disadvantaged youth, and then compared the rate for poor youth involved in the justice system versus poor youth not involved in the justice system, we would probably find their respective rates to be closer than what we see in conventional studies that compare offenders to all non-offenders, both poor and non-poor.

If such studies existed (and why don't they?) we would probably learn that when newly arrested, first-time offenders show up at the early stages of juvenile justice processing, they are not so different from other youth living in the same poor neighborhoods and from similar families facing the same types of economic and social challenges. When they come back for their second, third, or fourth offense, however, and when they start to qualify for secure detention, they are more likely to be youth with complicated lives and challenging home environments.

This new study underscores the relevance of mental health and substance issues for juvenile justice interventions, and the relevance is mainly at the deep end of the justice process.

The bottom line: Youth come into the juvenile justice system for a lot of different reasons. Some -- perhaps one in three -- will show up with mental health and substance abuse problems. For most youth, their offending was probably not "caused" by mental health and substance abuse problems, but by the time a juvenile has committed multiple offenses, and by the time he or she has been detained or incarcerated, mental health and substance abuse are likely to be salient for whatever treatment and intervention plan follows.

The above story is reprinted with permission from Reclaiming Futures, a national initiative working to improve alcohol and drug treatment outcomes for youth in the juvenile justice system.