“If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.” G.K. Chesterton

“If a thing is worth doing, it is worth doing badly.” G.K. Chesterton

I’ve used that quote as a guide for some time now, and nowhere more frequently than in my work promoting and practicing restorative and transformational approaches to conflict and harm. This was especially apparent to me this week, a week that both began and ended with me accompanying others along a restorative path with few markers other than my own experiences in the work and their desire to do things differently.

My friend and mentor, Dominic Barter, has presented what I consider to be the clearest vision of what a restorative response to harm can look like. Over and over he has emphasized that the response in my sphere is going to be different than in his, and that the model of Restorative Circles and the accompanying support systems are a “skeleton” that each community will flesh out in its own way.

This isn’t always easy to explain or accept, since as a culture we want and expect solutions to come to us prepackaged as turnkey products that we can sell for a certain value and that the buyer can implement without much effort. It is often uncomfortable to be viewed as an “expert,” especially when you know more than anyone that you don’t have specific answers to their situation.

The first meeting took place in another state. The victim of a serious felony knew something about restorative justice, and she knew that nothing like that existed in her area. Through her research she was able to track down my phone number. She called and explained the situation, then visited me. We didn’t know exactly how things would go, but I said I was up for giving it a try.

On the long drive over I talked with another friend and mentor, Tod Kington, of the Shawnee Conflict Center in southern Illinois. Restorative Circles include a pre-circle for facilitators, one that asks what is blocking us from seeing the humanity of all involved, including the facilitator, and that invites the facilitator to seek support for carrying out her role.

I expressed my worry and uncertainty. I didn’t know what I was getting into. I didn’t know many of the people. The authorities might question my credibility. We had no “real” system in place. He listened to it all and offered suggestions on how to approach the situation. The takeaway that I carried through the day was his reminder to stay connected to my intention and simply do my best.

“John, you are going in there carrying an understanding of what a restorative response can look like. They are in another system and might not recognize it. You are listening to the voices of those without power, and you can speak up and ask questions in a way that can help bring their needs to everyone’s attention.”

I kept that in the front of my mind throughout the long day. While talking to the victim, family members, friends, prosecutors, attorneys, police officers, the man who committed the crime and others I would be overcome with fear and the realization that I didn’t have all the answers. The current system is very powerful and presumes a lot of inherent certainty about what should happen. I was bringing the total opposite of that.

And it worked, or rather we all worked it out together. Every party in the somewhat chaotic day was willing to listen to others, to consider alternatives and to pay attention to the needs of the human beings involved. No one trumpeted the requirements of the system, or said, “We just can’t do that.” At the end of the day there was more mutual understanding and a response to the harm that met at least some of the needs of all involved. Together we slid the response in a restorative direction and had a significant impact on what happens next.

The second circle was in a nearby county, and held at the request of a counselor who’d been working with the participants. It was a parent and child, and the child had been in trouble at school since the beginning of the year.

It wasn’t the kind of trouble that could land you in court or juvenile detention, but instead a lot of lower-level disruption of class. The teachers had begun to focus on this kid, who would often be sent to the office or suspension even if it wasn’t clear who had broken a rule. The situation was spiraling down, and the parent had no idea what to do next. It wasn’t a stretch to imagine that the kid might end up in more serious trouble.

It also became clear that the parent had a style of conflict that sometimes made it more difficult for the kid to hear. Stress and worry led the parent to yell, to impose harsh sanctions and sometimes to lose hope. The situations at home and school began to influence one another cyclically. Getting calls from school every day was making the parent’s work life difficult, leading to less tolerance at home and the kid going to school angry and disconnected.

This was a situation that had deep roots and a high level of complexity because of other family members and their own conflicts. Over an hour into the meeting it seemed that they had achieved some understanding about how to change things at school. The kid agreed to look for different ways to handle conflicts with other students, and to ask the teachers for help in finding other places to do schoolwork.

I was ready to end the meeting when one of them said something about how they got along at home, and we were off again, talking for another hour at least, with the pain and difficulty becoming more and more open. For a facilitator this can be distressing. When things seem close to “resolution” we get hopeful and begin to relax, and it is disconcerting and sometimes disheartening to see folks dive back into the conflict.

I remembered an observation I have heard Dominic Barter make repeatedly. When we withdraw from conflict the voices get louder, so moving closer, though painful, is a way to get at the heart of what is separating us. It gives us a chance to lower our voices. This doesn’t come easily to us, since we have been trained mostly to avoid conflict or to move into a winning and losing framework.

This parent and child were willing to move closer, and to acknowledge that even though their conversations haven’t been easy (and still weren’t easy) they did want things to be different. The meeting didn’t end with a shining agreement that solved everyone’s problems (and made me look like a hero). Instead it ended with cautious acknowledgement that they could keep talking and that things could be different. Perhaps.

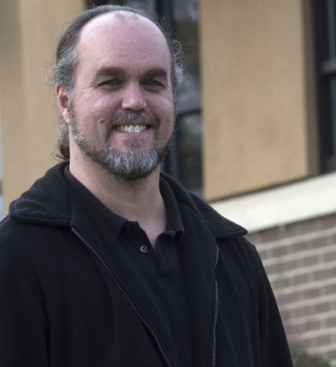

John Lash is the executive director of Georgia Conflict Center in Athens, Ga., where he works to increase the use of restorative justice approaches in the juvenile court, schools and the community, and teaches conflict management skills in various settings. He is a graduate of the Master in Conflict Management program at Kennesaw State University. He is a regular op-ed contributor to JJIE, where he also assists in website management and content curation.