Photos by Jacob Slaton, for the Arkansas Campaign for Grade-Level Reading

Since 2011, the Arkansas Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, supported by Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, has brought together a variety of stakeholders, including schools, early-childhood programs and the state department of education. The campaign also focuses on reducing chronic absenteeism by reaching out to frequently absent students early, rather than using negative ways to encourage attendance.

Every young life starts out with promise, and the adults who love a child yearn for that child to have a bright future.

But what if a simple barrier at an early age sets a child up for failure?

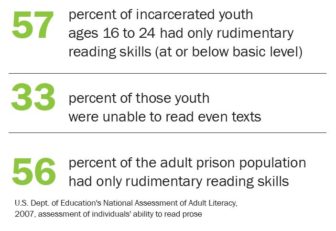

Difficulty in reading is such a barrier. Poor reading skill is a predictor of, among other things, involvement in the juvenile justice system.

“The literature shows a clear correlation between a grade-level reading problem and, later on, incarceration in the juvenile justice system,” said Ralph Smith, managing director of the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, a national collaboration of foundations, nonprofits, business leaders, and communities focusing on school success for children in low-income families.

Reading is so foundational, the Campaign has a nationwide effort to bring all kids to reading proficiency by the end of third grade.

Cities like Orlando have made literacy a cornerstone of their after-school and summer programs for kids. And a statewide campaign in Arkansas brings together school districts, teachers and volunteers to provide tutoring, mentoring and innovative summer literacy activities.

“There’s a very strong association between behavior problems and academic achievement,” said Deborah Stipek, former dean of the Graduate School of Education at Stanford University.

Stick and Sara Miles collaborated on research published in 2006 that followed children from first through fifth grade.

“We found that in first grade, achievement in literacy and reading predicted later aggression,” said Miles, who is now research director for the nonprofit Challenge Success.

“Our theory was that kids who are struggling as readers …” develop frustration and a negative relation to school. “It sort of snowballs,” Miles said.

They get more off-track as they get older.

“It can lead to low self-esteem and an antagonistic relation with school,” she said.

Chuang Wang, professor of educational research at the University of North Carolina, also has researched the link between reading and behavior.

“We found that students who have behavior problems also have problems in reading,” he said of a study involving second graders published in 2011.

“If you improve reading, then you might have less problem with delinquency,” Wang said. “They are highly connected.”

He cautioned that poor reading does not cause delinquency, however. Research shows correlation but not causation.

From a child’s point of view

Smith, with the Campaign for Grade-Level Reading, describes it this way: “Imagine being a fourth-grader who realizes they can’t read and apprehends that they are in serious trouble and no cavalry of adults is mobilizing to save them.”

“What’s the incentive to resist oppositional behavior … to be respectful of adults and trust adult authority?” he said.

“You begin to understand how a young person … could get on a path that leads them to the juvenile justice system,” Smith said.

Approximately 500 volunteers tutor 1,200 children through AR Kids Read in four school districts in Pulaski County, Arkansas.

Three vital areas need to be addressed according to Smith: the school readiness of young children, the chronic absenteeism that causes some children to fall behind and the loss of knowledge during the summer. Kids often start out behind, fall behind further due to chronic absenteeism and lose skills in the summer, he said.

After-school programs can also address the problem in several ways, Smith said. They can:

- enrich the school curriculum

- add opportunities for kids with moderate or good reading skills to fall in love with books, and

- build the skills of marginal and struggling students.

Smith said that after-school programs need to be more intentional in reaching and engaging the students who need extra time and assistance, not just those who happen to show up after school. Programs should make an effort to find the students who could benefit the most, he said.

Efforts in Arkansas

Since 2011, the Arkansas Campaign for Grade-Level Reading has been supported by the Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. The campaign has brought together a variety of stakeholders including schools, early-childhood programs and the state department of education, said Angela Duran, campaign director.

A large tutoring effort known as AR Kids Read spans four school districts in Pulaski County, where about 500 volunteers tutor 1,200 children.

In Springdale, Arkansas, the Parents Taking Leadership Action focuses on getting parents involved in their children’s education. The district includes many Latino parents as well as a large group of immigrants from the Marshall Islands who were encouraged to get to know teachers and take English classes at the school, Duran said.

The campaign also focuses on reducing chronic absenteeism by helping schools use data to pinpoint frequently absent students early and reach out to families in positive rather than negative ways to encourage attendance, she said. For example, a school may inquire about the family’s needs and connect the family to resources instead of focusing solely on truancy.

In addition, five summer programs with a literacy component are funded by the Arkansas Community Foundation.

A large reading program in more that 16 U.S. cities, Read for Success, is sponsored by the nonprofit Reading is Fundamental. It targets the 80 percent of children from economically disadvantaged communities who lose reading skills over the summer. Through the program, schools and community-based groups receive a collection of books, as well as training in ways to use the materials.. Children take home books during the summer and have access to related activities online.

Social, emotional skills required

Teaching reading skills is very important, said Spivek of the Stanford Graduate School of Education. But supporting the development of social and emotional skills and self-regulation is critical too, she said, noting that research shows poor self-regulation predicts both poor reading ability and poor behavior.

“We need to teach kids better early on,” she said.

Teacher training is the crucial ingredient, Spivek added. “What matters most is teaching. It’s more important than curriculum.”

“Focus on reading and self-regulation and social and emotional skills and math,” she advised.

Miles said that high-quality after-school settings with trained staff are extremely valuable.

“It’s a great time to do some of that social and emotional teaching and learning,” she said, especially for low-income kids who don’t necessarily have the opportunity for a lot of out-of-school activities.

Ten years ago, the city of Orlando launched the Parramore Kidz Zone in its lowest-income neighborhood. The program grew to offer six free after-school tutoring sites and a comprehensive pre-kindergarten program, as well as youth development programming that helps kids with employment, college access, educational and cultural experiences, and leadership development.

The city developed a summer learning program for elementary-school children at eight recreation centers. Twelve teachers provided a summer reading academy at each location using project-based activities.

Children who struggle with reading are going to be frustrated, Spivek said. If you only focus on academics with them you are “missing the big picture,” she said.

Children who struggle with reading are going to be frustrated, Spivek said. If you only focus on academics with them you are “missing the big picture,” she said.

Focus on the whole child, she said.