Katy McCarthy / JJIE

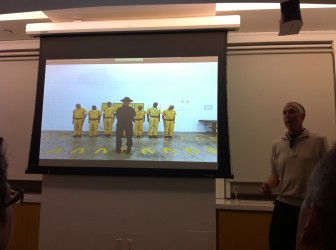

Richard Ross speaking at the Vera Institute of Justice.

NEW YORK - Photographer Richard Ross can’t pin down the moment he found his calling.

It could have been on the concrete floor of the Harrison County Juvenile Detention Center in Biloxi, Miss., where he sat photographing a 12-year-old inmate in a yellow prison jumpsuit as he gazed at graffiti of spaceships and aliens scribbled on the wall of his tiny, decrepit cell.

Maybe it was the young inmates trying to sleep on the floor of the intake room of a Los Padrinos Juvenile Hall in Los Angeles. Or the facility for young female offenders in California where the administrator told him all 88 residents were victims of sexual abuse.

It could have been his visit with Ronald Franklin, who ran away from home at 13 after his mother tried to kill him, got involved in an armed carjacking and ended up in a Miami juvenile detention center where he waited four years without a trial.

Somewhere in Ross’ travels chronicling the conditions of boys and girls in prison it happened.

“I can’t remember an ‘ah-ha’ moment, but at some point you find something that means more to you than a lot of other things you’ve done in the past and you know you can’t go back,” Ross said in an interview this week as he visited New York to mark the opening of an exhibit of his photographs at the Ronald Feldman Galleryin SoHo and to give a talk on his work at the Vera Institute of Justice in lower Manhattan.

“I can’t remember an ‘ah-ha’ moment, but at some point you find something that means more to you than a lot of other things you’ve done in the past and you know you can’t go back,” Ross said in an interview this week as he visited New York to mark the opening of an exhibit of his photographs at the Ronald Feldman Galleryin SoHo and to give a talk on his work at the Vera Institute of Justice in lower Manhattan.

Over five years, Ross, a longtime art professor at UC Santa Barbara, photographed and interviewed more than 1,000 juveniles incarcerated across the country as part of his “Juvenile In Justice” project. Each story has it own grim details, and for Ross it adds up to a stinging indictment of this country’s juvenile justice system.

Each night some 70,000 juveniles, a disproportionate number of them minorities, are incarcerated in America, where the rate of juvenile incarceration far outstrips that of other developed nations. To Ross and other advocates, the far majority of these kids, often the victims of abuse and violence, were in the wrong place at the wrong time and have no business in facilities that resemble the jails for hardened criminals.

Ross, 65, hopes his photos, which he calls a “visual data bank,” will get policymakers to reform the juvenile justice system away from punishment, isolation and detention and toward the type of rehabilitation and education he thinks could help these youths get their lives on track.

Ross called the work physically and emotionally “punishing,” but said he has no plans to stop.

“It’s a threshold you’ve passed and you’re not going to retreat from it,” he said. “I can’t just close the book and say I’m done, there’s too many lives at stake.”

An acclaimed artist who made his reputation shooting for major publications and the Getty Museum, Ross said he understands the power of images to shape public opinion and drive policy. He said the iconic 1972 photo of a 9-year-old Vietnamese girls running down the street naked and screaming after a napalm attack changed his life, and that’s where he’s the set bar for his photos of incarcerated youth.

Ross, who grew up in Brooklyn the son of a New York City cop, visited more than 200 juvenile detention facilities in 31 states for the project that became Juvenile In Justice. He published a book of his photographs, with an essay by Ira Glass and excerpts of interviews he did with the subjects. An exhibit of his work opened in Paris last June and landed in New York this month after stops around the country.

Although some artists avoid connecting their work to overt political statements, leaving any hard and fast conclusions to the audience, Ross takes a different tact.

“I’m trying to have a viewer look at that and basically realize this is not a place for kids,” Ross said. “Teenagers are by definition dysfunctional. They make mistakes. Then they’re put in rooms that are 8x10 concrete? How is that going to change them or help society?”

About 100 people turned up Wednesday night to hear Ross speak at the Vera Institute, which has its office on the 12th floor of the Woolworth Building. Fit at 65, with an angular face and gray hair going white at the edges, there’s still a little bit of Flatbush in Ross’ voice, despite more than three decades in California.

Ross’ father was a cop in the 70th precinct for several years, but was forced to leave the force because of a gambling and bribery scandal involving Harry Gross, a major bookmaker based in Brooklyn. Ross, whose father took him to museums around the city and often dropped him at the Brooklyn Museum on Saturday mornings, recalls those days as a time when “Brooklyn was truly hip” and said growing up as the son of a police officer influenced his work.

“We’re still doing things to please our parents,” Ross said. “That never changes.”

Ross said that of the 70,000 or so juveniles in custody across the country on any given night, only about 12 percent are there for violent offenses. He said that some kids are “sociopaths who you should be scared of,” but that the number of children caught up in bad circumstances, or who don’t belong in a prison, far outweighs the truly hard cases.

“Mostly they’re just people you’re pissed off at,” Ross said during his Vera talk. “You have to look at these kids as being victims, for the most part.”

Despite the draining toll of constantly interacting with incarcerated young people, Ross plans to push ahead with his project, saying he feels a bit like Al Pacino’s character Michael Corleone in Godfather III, referencing his notorious line from that movie: “Just when I thought I was out, they pull me back in.”

He’ll shoot in California next week, and has plans to visit juvenile facilities in Kansas and New Mexico in coming months.

Many of Ross’ images, projected on a screen in the front of nearly a packed conference room as he described his work, elicited gasps from the crowd Wednesday night. The strongest reaction came from the startling juxtaposition of two jail cells, both concrete and unadorned. One picture was taken at a youth facility in El Paso, Texas, and another at the military prison at Guantanamo Bay.

The rooms were strikingly similar, with a key difference: there was a window in the room at the jail in Cuba.

This story was produced by JJIE’s New York City Bureau.

Photo by Richard Ross.