Allison Hyra

Jessica R. Kendall

Young people in this country are exposed to violence or traumatic experiences at alarming levels.

A 2011 survey funded by the U.S. Department of Justice (which formed the Defending Childhood Initiative) found that most American children have been exposed to violence in their homes, communities or schools.

The survey showed that more than 60 percent of children between birth and age 17 had been exposed to violence in the previous year, either directly or indirectly — having witnessed a violent act, learned about a violent act against a family member or close friend, or experienced a threat against their home or school.

Almost half of all American children had been assaulted and about 1 in 10 had been the victim of maltreatment — abuse, neglect or abandonment. Multiple victimizations were common, with one-third of all children experiencing at least two or more direct victimization experiences.

The latest research in brain science suggests that acute or prolonged exposures to these experiences, without protective factors, can affect children’s brain development.

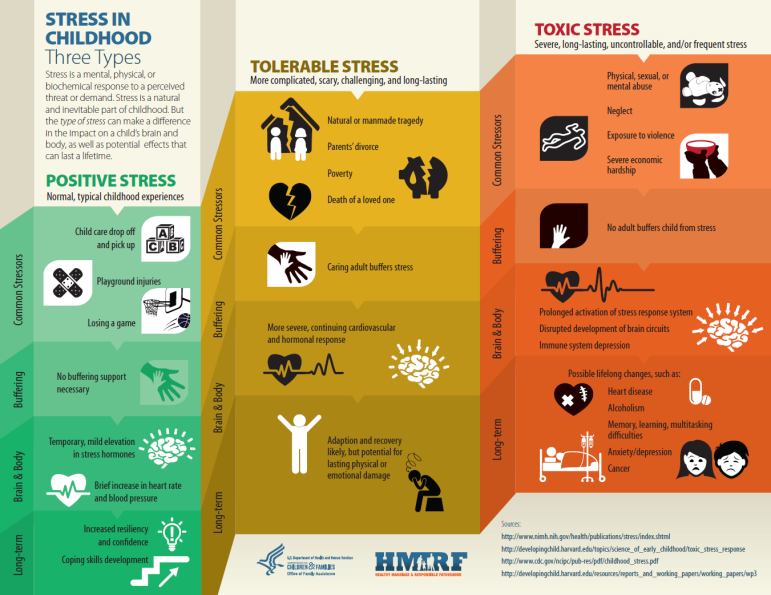

This neurological childhood phenomenon is called “toxic stress.” Experts have found that some children experience stressors so toxic that their developmental and brain trajectories alter — affecting not only their childhood but their entire life.

Harvard University’s Center on the Developing Child defines toxic stress as “occur[ing] when a child experiences strong, frequent, and/or prolonged adversity — such as physical or emotional abuse, chronic neglect, caregiver substance abuse or mental illness … without adequate adult support.”

This stress, if not buffered by adult protective factors, can overload a child’s stress response systems, disrupt their hormones and brain development, and cause long-lasting cognitive, emotional and behavioral effects.

Toxic stressors can fundamentally alter the circuitry in a growing child’s brain. These physiological changes can appear as a range of actions or behaviors relating to problem-solving, impulsivity, self-regulation, memory, learning and executive functioning.

According to a 2015 brief from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation (OPRE), younger children who experience toxic stress may exhibit changes in their eating and sleeping patterns, avoid certain locations or events, be highly irritable, mistrust adults, regress or be overly clingy. Adolescents may demonstrate excessive risk-taking behaviors such as early drinking, tobacco use, gambling or sexual promiscuity. These behaviors can affect their connections to positive social networks and lead to disengagement from school and participation in criminal activities.

Not every child who exhibits these behaviors or actions has experienced toxic stress. And not every child exposed to serious stressors experiences long-term negative effects. However, it is important for child- and youth-serving professionals to understand the prevalence of violence exposure among children to be able to identify its signs and adopt a trauma- and toxic stress-informed approach to practice.

Not every child who exhibits these behaviors or actions has experienced toxic stress. And not every child exposed to serious stressors experiences long-term negative effects. However, it is important for child- and youth-serving professionals to understand the prevalence of violence exposure among children to be able to identify its signs and adopt a trauma- and toxic stress-informed approach to practice.

Organizations that work with and serve children and youth can become more trauma-informed by assessing their practices and procedures and the extent to which they have trauma screening, assessment and service practices. Becoming trauma-informed also includes training staff on identifying and appropriately responding to adverse childhood experiences, stress and trauma, as well as building an organizational environment that is culturally responsive.

Similarly, individuals working with young people can learn about toxic stress and its symptoms, as well as how to prevent them. A key component to whether stress becomes toxic is the existence of a loving, caring, supportive and consistent adult figure to buffer the prolonged, frequent or significant stressors in a child’s life.

Protective adults in young people’s lives don’t have to be parents or caregivers. Committed, long-connected teachers, mentors or case workers can also help identify and reduce childhood stressors that may affect brain development. A recent study from OPRE suggests the following activities and behaviors can help mitigate the effects of toxic stress:

- Provide social support. Listen to young people, be empathetic and connect them with additional resources and other supportive individuals.

- Be authoritative. Be clear about your expectations and goals for your clients, such as completing school or receiving professional career training, but also couple that “high demand” with a strong emphasis on how much you care for them as a person and want the best for them.

- Interact in a responsive way. Young people want to know that they have been “heard,” and that their thoughts, worries and opinions are valid and worth attention. By responding to their thoughts, rather than dismissing them, young people feel valued and treated like equals.

- Provide mentoring opportunities. Young people benefit from hearing about how adults in their lives also struggled in adolescence. This offers the adult an opportunity to show the young person how they too can succeed as adults. Sharing advice and providing specific suggestions can help guide young people down a positive path.

- Give access to an enriched environment. Young people benefit from engaging in a range of activities and enrichment opportunities. Taking them to cultural events, museums, parks and restaurants exposes them to cultural, economic and social diversities.

A 2013 video by the Center on the Developing Child notes the most important thing a child needs to thrive in her environment is her family, but it also acknowledges her environment extends to other important adults in her life: in school, in her neighborhood and community. Child and youth service professionals, and the organizations they work for, are uniquely positioned to help reduce the effects of toxic stress, increase resiliency and help young people build paths to successful adulthoods.

Allison Hyra, Ph.D., is a Fellow at ICF International where she translates research and evaluation findings into actionable advice and support to help human service professionals improve their work.

Jessica R. Kendall, J.D., is a technical specialist at ICF International where she works on projects relating to Temporary Assistance for Needy Families and workforce programs.

Pingback: ;News Roundup | Reclaiming Futures

Pingback: How Curfews Have Changed Through History; News Roundup | Reclaiming Futures

Great visual. Where can I obtain these as handouts for our statewide health fair program?

Pingback: OP-ED: Translating the Science of Childhood Stress Into Youth Service Practice | Cruncheez