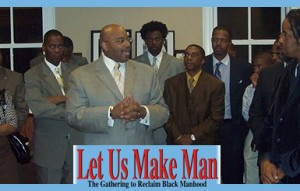

Boazman

Prevalent media portrayals of young African-American males as violent and angry make Ayo Tinubu cringe, but he can relate. At the age of 16, some guys at school had been bullying him. Finally fed up with the harassment and threats, he and some friends planned to retaliate. They skipped school at North Atlanta High School that day in 1996 then showed up that afternoon with brass knuckles and knives in tow, ready for battle. A quick-thinking school bus driver anticipated trouble and alerted the school principal before any violence erupted.

The good news is that Tinubu never got to use the baseball bat he’d brought to campus (nor did his friends use their weapons). The not so good news, however, is that he was promptly suspended. Derrick Boazman, then an Atlanta Councilmen who had worked for Tinubu’s mother, rushed to his aid. Boazman lobbied the principal to allow Tinubu back in school with the assurance that he’d make sure that Tinubu would never do anything like that again. “I could have made a poor temporary decision that could have affected the rest of my life,” recalls Tinubu, now 31. “It was really the grace of God that saved me from making such a big mistake. Unfortunately too many of my fellow young black brothers aren’t getting that second chance like I did. They don’t have the support that I did at that time.”

Tinubu

Boazman and Tinubu made good on that promise to the principal. Tinubu graduated and later enrolled in Clark Atlanta University. Boazman still mentors him to this day. Later this month both men will join forces for an event they hope will provide other young African-American men with the same opportunity to thwart trouble and embrace success. On April 29 Boazman hosts his fifth annual “Let Us Make Man: The Gathering to Reclaim Black Manhood,” a two-day forum at Fort Valley State University in Fort Valley, Ga., a small town about 100 miles outside of Atlanta. The event aims to provide resources for parents, children, educators, churches, community organizations, criminal justice industry workers and child advocates to acquire the knowledge and resources needed to help legions of young black males in crisis.

“This event is about rejecting stereotypes and redefining black male hood,” says Boazman. “Our purpose is to provide anyone who cares about this issue, the tools that they need to help. We’ve found that a lot of people want to help, but they don’t know how. Because the image of black males is portrayed as so menacing, a lot of people are scared to even go into the hood to help. We’re going to show them how to reach out.”

The problem the conference seeks to address is apparent. Staggering statistics seemingly stack up against African-American men and boys daily; the highest school dropout and incarceration rates nationally and locally paired with disturbingly low college enrollment and employment numbers. As JJIE.org reported late last year, one study even suggested that the federal government intervene.

“The mere fact that African-American males make up 89 percent of the inmate population in Fulton County but are only 20 percent of the total population speaks to the critical need,” says fellow organizer Michael Langford. “The fact that 88 percent of them don’t have a GED or a high school education speaks to how much more we need to be involved in the lives of our black kids.” Only 41 percent of black men graduate from high school in the United States, according to a study by the Schott Foundation for Public Education. One report found that one in three black men between the ages of 20 and 29 years old is under correctional supervision or control.

Having a positive male role model, Langford says, makes a major difference. “That is why ‘Let Us Make Man’ is critical,” says Langford, president of the United Youth Leadership Conference, an Atlanta-based mentoring program. “This is one of the most dynamic gatherings of men that I have ever been a part of. It’s a call to action to anyone interested in taking action. We provide a blueprint on how to organize and get things done.”

Having a positive male role model, Langford says, makes a major difference. “That is why ‘Let Us Make Man’ is critical,” says Langford, president of the United Youth Leadership Conference, an Atlanta-based mentoring program. “This is one of the most dynamic gatherings of men that I have ever been a part of. It’s a call to action to anyone interested in taking action. We provide a blueprint on how to organize and get things done.”

The forum begins with a Friday night awards ceremony paying tribute to exceptional male mentors. The second day, dubbed “the gathering” is dedicated to both learning and teaching. Breakout sessions, which organizers refer to as “modules,” explore such topics as “Law & Black Society,” “Mentoring,” “Educating Black Males,” “Spiritual Development,” “Restoring the Black Family” and “Black Youth Leadership.” Adds Boazman. “We also have a session called ‘Healing Oppression’s Wounds.’ A lot of our young men are walking around with a lot of hurt and loss. If they don’t deal with it, it affects every aspect of their lives; then we wonder why he can’t finish school or keep a job.”

TV's Judge Penny Brown Reynolds and Atlanta Pastor Rev. Tim McDonald are among this year’s keynote speakers. Past headliners include actor Danny Glover, filmmaker/actor Robert Townsend, talk show hostess Oprah Winfrey’s beau Stedman Graham and Chicago-based priest and social activist Michael Pfleger.

Boazman, an Atlanta native, says he came up with the conference idea seven years ago during a conversation with his colleague Mawuli Davis. They were both bothered by the descriptions of black men they’d heard from a group of teenage boys visiting Atlanta from Spain. “In their minds, all black boys had gold teeth, were tatted up (had tattoos) from top to bottom and were unintelligent,” remembers Boazman, now a talk radio show host on WAOK 1380 AM. “We had to tell them ‘no, that’s not what black boys are, that’s just what’s mostly projected in the media. And even if they are tatted up with sagging pants, that’s not necessarily an extension of who they are completely.’”

Glover addresses attendees.

Boazman says Mawuli, a local criminal defense attorney, also expressed concerns about overrepresentation in the prison population. “He talked about how he saw so many young 14 and 15-year-old black boys going to prison for a mandatory 10 years for crimes like armed robbery,” he says. “Then we came up with the idea for the forum.”

Turnout for the event has mushroomed over the years. Last year 800 was expected; 1,500 showed up. “Seeing all of those faces at 7 a.m. on a Saturday morning trying to find solutions was humbling,” recalls Tinubu.

Boazman, too, identifies with Tinubu’s troubled teen years. He says men like the late civil rights leader Rev. Ralph David Abernathy and State Senator Arthur Langford Jr. helped him channel his boundless “energy” into constructive outlets when he was young. Boazman still volunteers every summer for the late senator’s Teen Leadership Institute for black male teens held on the Atlanta Technical College campus.

Tinubu says he’s honored to participate in a forum that explores the root causes of the disparities young black boys and men face in American society and one that also provides concrete tools for solutions.

“A lot of these boys get blamed as the problem, but this is really the failure of adults,” he says. “The educational system has failed them, their families have failed them. They’re born into unstable homes with no real role models. They’re force-fed negativity, violence and misogyny and then are somehow expected to excel. We feel like if we save just one young man with this forum, we’ve done our job. And hopefully that one will eventually reach out and save another one.”

For more information on Let Us Make Man 2011 or to register, visit http://www.letusmakeman.net/home.htm.

___________________________

Got a juvenile justice story idea? Contact JJIE.org staff writer Chandra R. Thomas at cthom141@kennesaw.edu. Thomas, a former Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellow and Kiplinger Public Affairs Journalism Fellow, is an award-winning multimedia journalist who has worked for Atlanta Magazine and Fox 5 News in Atlanta.