LISTEN:

In a four-part series, the Southern Education Desk and the Juvenile Justice Information Exchange are examining the new law and its impact on students, families and schools.

After 11-year-old Jaheem Harrera committed suicide in 2009, some of state Rep. Mike Jacob’s constituents in DeKalb County, Ga., in suburban Atlanta, asked him to take a look at the state’s existing rules against bullying in schools.

He did, and as he told an audience at a fundraiser for the group Georgia Equality last year, he didn’t like what he found.

“It was so inadequate, in fact, that the Jaheem Harrera situation was not even covered by the existing law,” Jacobs said. “It only applied to grades six through 12.”

So Jacobs proposed making the state’s anti-bullying measures apply to elementary schools too. The law that the Legislature passed also expands the definition of bullying beyond physical harassment only. It requires schools to notify parents of both bully and the victim whenever bullying happens. And schools must now remove students caught bullying three times and send them to an alternative school.

“And if they don’t do that, they will lose state funding,” Jacobs said. “So there are significant consequences to local school districts not enforcing the new anti-bullying law.”

Forty-seven states have now passed legislation to combat bullying, and the watchdog site Bully Police now ranks Georgia among states with the most muscle behind their policies.

The state education department developed a new model policy against bullying at the end of last year. School districts were given until the start of this school year to update their own policies and put the law into action.

Linda Horne, who’s responsible for helping schools implement the law in Houston County, in south central Georgia, says the district convened a committee of school staff members to facilitate the process. Then they fanned out to their schools, helping other teachers and administrators understand what the law means.

“We talked about bullying being severe, persistent, [and] pervasive,” Horne says. “So that it creates an intimidating or threatening educational environment; so that it causes another person either physical harm or bodily harm or that the person perceives that it could cause that.”

Knowing the exact definition of bullying is important, since the new law requires every adult employed by a school system to report bullying if they see it.

“The enforcement of bullying policy can lead to some really thorny problems,” says Bill Nigut of the Georgia Anti-Defamation League.

Nigut lobbied for the passage of the revamped bullying law for two years. He says the legislation fixes some big problems with the old law. But when you drill down to the school level, he says, even strong bullying laws raise difficult questions.

“A great example -- the new law does have protections for online bullying. But one of the questions that is being grappled with in school systems around the country is to what extent do schools have responsibility for enforcing bullying from one personal computer to another?” Nigut says. “That’s unsettled law at this point.”

Some districts are also beginning to use more sophisticated definitions of bullying than the law requires, Nigut says. His organization, for example, is urging districts to classify different types of bullying based on the motivation of the bully and who the targets are -- like singling out bullying based on religious belief or sexual orientation.

More broadly, Linda Horne of Houston County says the country is in the midst of a cultural shift away from a time when bullying behavior was seen as just another part of growing up.

“For many years we looked at bullying as being what many people would say -- well they’re just being boys being boys or girls being girls,” Horne says. “And I think that over the years, we’ve begun to see, you know we need to take a look at this.”

And that’s led to a new level of scrutiny. The federal Department of Education hosted a conference at the end of September on stopping bullying in conjunction with seven other federal agencies and a slew of national non-profits. The Anti-Defamation League’s Bill Nigut says the attention signals that stopping bullying is an idea whose time has come.

“When you have any number of federal agencies now deeply involved in fighting school bullying, it tells us clearly that this is now deadly serious business,” Nigut says.

But increased attention raises more unanswered questions. Elizabeth Jaffe of Atlanta’s John Marshall Law School says one involves what happens when students’ free speech rights collide with other students’ right not to be bullied.

Jaffe notes that existing case law allows schools to limit students’ speech to protect the safe environment of the school.

“However, with the litigiousness of our society, I think we’re going to see more and more lawsuits about incidents that occur,” Jaffe says. “For me the question goes back to prevention.”

So the question becomes not just how to respond to and punish bullying when it happens, but how to prevent it from happening at all.

It may take some time to tell whether the new rules in Georgia are actually cutting down on bullying -- in general, reports of bullying spike as schools begin to track it and as students and parents become more aware.

But lawmakers, advocates and schools are hoping that in time, the changes will lead to more peaceful, respectful schools -- that in turn promote more learning.

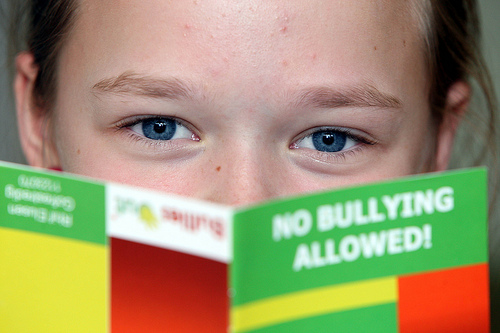

Photo credit: Working Word/Flickr