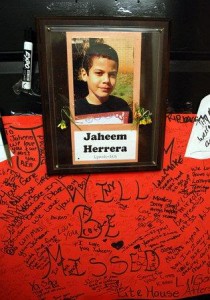

The start of the school year is extra hard for Bermudez and her family in light of Jaheem’s absence. Bermudez says she tries to be strong for her three daughters who still attend school in DeKalb County, just to the East of Atlanta.

The start of the school year is extra hard for Bermudez and her family in light of Jaheem’s absence. Bermudez says she tries to be strong for her three daughters who still attend school in DeKalb County, just to the East of Atlanta.

“They’re hurt; that’s something that will never go away,” she says of her three girls. “They miss their brother. They’re always bringing up stories about him. Sometimes we cry together; but in school, regardless of what happened, they’re still doing good.”

Bermudez says she takes solace in knowing that her son’s story inspired state lawmakers two years ago to pass a law beefing up bullying policies at all Georgia schools, a policy that had not been updated since 1980.

The new law:

• Defines bullying more broadly than before.

• Requires local school systems to adopt policies on dealing with bullying.

• Expands the policies to include elementary school students, particularly kindergarten.

• Requires parents to be notified any time their child is bullied or bullies someone else.

• Mandates students who bully in grades six through 12 be placed in an alternative school after the third offense.

Bermudez hopes the law will keep other families from facing a similar ordeal, but she wishes it formally honored Jaheem.

“The same way they have the Amber Alert I think they should have named it the Jaheem Herrera Anti-Bullying Act, so that people can know that because of him it’s been passed and it’s been strengthened,” she says.

Jaheem’s 12-year-old sister Yeiralis hopes it will help protect other kids.

“Well, they’re trying, so far so good,” she says of state lawmakers. “But wherever, what school you go to there’s still going to be bullies.”

She says last year a boy in her class repeatedly teased her about her brother’s death. Her mom says she filed charges with the school resource officer but the school never responded. The boy’s parents eventually withdrew him from the school.

“They picked on me about my brother’s death and teased me about it and just stuff,” she says. “But I ignored them and told the teachers and stuff. And I think that’s what all kids should do; not try to solve it themselves.”

Yeiralis has this advice for children:

“Stop the bullying,” she says. “Tell your parents. Well, don’t take it in your own hands and do something stupid that can hurt your family.”

DeKalb Schools Assistant Director of Student Support Services Jennifer Errion agrees that the law is a positive step. She notes that DeKalb updated its bullying policy well before the recent deadline.

“Well, I think it puts a spotlight on behavior so that it is seen as violation of human rights rather than as a rite of passage,” asserts Errion, who says she’s been doing “school climate” work in DeKalb for about 20 years.

Continues Errion:

“We’re having all faculty members and all students take an anti-bullying or bullying awareness pledges,” she says of the system’s campaign. “You know, where [students, staff, teachers and administrators] are taking a stand against bullying.”

Errion says DeKalb’s updated policy requires that every incident be investigated. Administrators have “a gradiated level of response” to each incident. Three consecutive bullying episodes don’t have to occur before school leaders are required to take action.

On a lazy Sunday afternoon Bermudez and her daughters flip through Jaheem’s baby pictures in a frayed photo album; the images seem to remind them of happier times.

“He was a quiet little boy,” recalls Bermudez, smiling. “He loved to draw. He loved to dance. His favorite singer and dancer was Michael Jackson. And every time you looked up he’s doing a Michael Jackson dance. He was like a little clown at home.”

The memories are bittersweet for Yeiralis.

“I got on his nerves really, but he was really smart,” she says, as her giggle fades into a grimace. “I don’t know why they bullied him, because there’s nothing to bully him about. He kept telling [school administrators], but they never handled the situation. It just got too out of hand and he had to take his life.”

Bermudez and her friend Jackson will continue to push for justice for her son. Jackson says the need is greater than ever.

Bermudez and her friend Jackson will continue to push for justice for her son. Jackson says the need is greater than ever.

“The AJC [Atlanta Journal-Constitution] published a report that showed, that documented on paper, that DeKalb County had over 600 bullying incidences in their county,” she says. “But when you look at it, you have all these students. There’s got to be more incidences of bullying, but they just didn’t report it. So reporting is such a big issue.”

In a school district as large as DeKalb’s, the third largest in Georgia, Jackson says she suspects that there are “far more cases” of bullying. DeKalb has a student enrollment of more than 102,000 students in 143 schools and centers, and employs 13,285 full-time employees.

Bermudez insists that her family and supporters, which she dubs, “team Jaheem,” will not back down without a fight.

“There was bullying,” she says. “Somebody has to be accountable for what happened to my son. I can’t let this go. It might be years from now, but I’m going to still push for justice.”

Bermudez says she does not currently have any legal action pending against the school system because she does not have legal representation. She and her friend say their point-by-point written response to the school system’s review will be released soon.

“Regardless of if he’s not here physically, I feel my son next to me," she says. “He’s not going to rest. I feel it. He’s not going to rest until I get some justice.”

Photo credit: smokenmirrors_photo/photobucket

Photo credit: gapride2008/photobucket