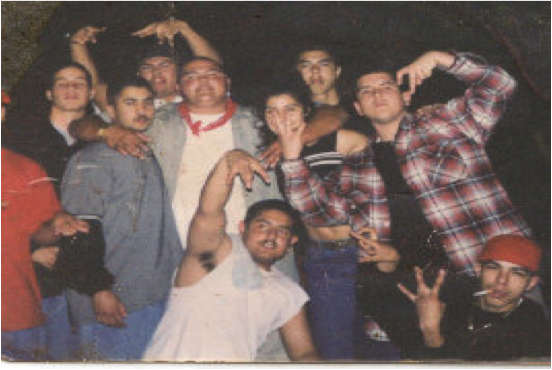

A photo of Westside Norteno 14 in Cobb County, Ga. Photo confiscated by Cobb County CAGE Unit, Sept. 20, 2003. Courtesy of Rebecca Petersen.

When most people think of gangs and the criminal activity often associated with them problems of the inner-city may come to mind -– issues that are far from their manicured suburban lawns, something that could never touch their lives directly.

But the demographic makeup and geographic location of gangs are changing, according to Rebecca Petersen, author of Understanding Contemporary Gangs in America and a Criminal Justice Professor at Kennesaw State University near Atlanta*.

“We have seen this trend of gangs moving out of the city and into the suburbs for 20 years now,” Petersen said. “We don’t associate the suburbs with people being poor or homeless, but it’s one of the fastest growing populations [in the suburbs].”

While gangs are not exclusively comprised of low-income members, the correlation between harsh economic conditions and the proliferation of gang activity has been documented in communities around the country since at least the late 1980s.

In the decade leading up to 2010, the suburban poor in major-metropolitan suburbs grew by 53 percent, compared to an increase of 23 percent within the cities, according to the Census Bureau. As a result, the majority of the traditionally urban poor population now resides in suburban communities throughout the United States. In 2010, suburbs housed about a third of the nation’s poor, outranking major urban centers that accounted for about 28 percent of the impoverished population.

Part of the problem, Petersen noted, is that many suburbs and outlying towns don’t have well developed social support systems or infrastructure to deal with the influx.

A number of factors contribute to the shift of population to the suburbs, including immigration, availability of affordable and subsidized housing and economic stagnation. According to a 2009 study by the National Youth Gang Center, quality of life issues, such as employment or educational opportunities, were the most significant factors in gang member migration, and not the expansion of existing criminal activity.

“More often than not it’s not a gang migration, but an individual migration,” said George Knox, Director of the National Gang Crime Research Center, adding that family ties and economic opportunities usually underpin the relocation of gang members. “It’s not as if [a gang] suddenly got together and took a vote on whether to move.”

Nationally, gangs have been migrating from the inner city to suburban communities for more than three decades, starting slowly in the 1970’s and becoming “entrenched in many suburban communities across the nation” during the 1990s, according to the "Attorney General's Report to Congress on the Growth of Violent Street Gangs in Suburban Areas" in 2008. According to the same report, suburban gang migration also contributed to an increase in violent crime, including homicide, within a number of the suburban communities they moved to.

For example, in 2007 law enforcement officials in Irvington, N.J., a Newark suburb, reported 23 homicides for the year – 20 of which were gang related.

“The suburbs just aren’t geared for this type of issue,” Knox said. “Usually [the suburbs are] more vulnerable, and gang members know this.”

According to Petersen, most gang-related violent crime was directed at rival gang members, while a variety of less-serious offenses made up the majority of overall gang criminal activity.

Looking at arrests in Cobb County, Ga., an Atlanta suburb, Petersen found that about 60 percent of gang member arrests were for misdemeanor offenses. The most common crimes included property damage, drug possession, theft and burglary – along with arrests for robbery, aggravated assault and statutory rape.

From Atlanta, a closer look:

In metro Atlanta, gangs have long been seen as a largely black, inner-city problem. But when Peterson moved to the city in 2002 she was “shocked” to learn that the majority of gangs were of Hispanic origin and mostly operated away from the city center.

“Immigrants are moving to the suburbs as their first step when arriving here in the United States,” Petersen said, “where before they would typically go to the cities, and then the suburbs.”

In Cobb County, Ga., the focus of Petersen’s recent research, Hispanics account for about 74 percent of the known gang population – a demographic trend that is mirrored in national data.

“All you have to do is drive up and down the highway in Atlanta to see the evidence of gang migration,” Knox said.” There’s MS 13 (a notorious Hispanic street gang) markings prominently displayed everywhere.”

Unlike in the past, many of these gangs don’t claim “turf,” or a given geographic area with strict boundaries, as their own, Petersen said. Instead, members can be scattered across a wide area and often travel outside their own neighborhood to commit criminal activity.

Gang recruitment, especially among Hispanics, largely takes place in middle school where kids are still impressionable and have a stronger desire to fit in than older teens, Petersen said. For law enforcement, it’s also a time to drive home the dangers and consequences associated with gang life.

Since Cobb County’s inception of the Cobb Anti-Gang Enforcement (CAGE) Unit in 2002, the operation has documented more than 53 different gangs with more than 600 known members. Petersen said the actual number of gang members is likely three times that of known members.

Gang involvement declined throughout the late 90S until hitting an all-time low in 2003. Since then, the number of gangs around the country has slowly crept back up, but still hasn’t hit previous highs. Gang activity continues to be largely centered around major metropolitan areas, with two-thirds of all gangs residing, the National Gang Center reports.

*This is a publication of the Center for Sustainable Journalism at Kennesaw State University.