By Eric Ferkenhoff and Maggie Lee

By Eric Ferkenhoff and Maggie Lee

The violence that stains Chicago is a long way from Washington, D.C., where the U.S. Supreme Court ruled Monday it was not just to lock up juvenile killers for life without parole in most cases. The court, reasoning children should not face what amounts to death behind bars, voted 5-4.

Monday’s decision had been anticipated since arguments were heard in March on two cases out of Alabama and Arkansas dealing with 14-year-old convicts, and won the applause of children’s and rights advocates and scorn from those who believe punishment should be equal to the crime.

“I’m feeling very good, hopeful,” said Julie Anderson, 55, whose son was convicted of murder at 15 in 1995. “We’ll see how it plays out, but my son defintely qualifiies under this ruling to have his sentence looked at again.”

She added: “And there’s so many of them, these people who were only children. Most are of color, too – something like 86 percent, and they don’t commit 86 percent of the crime.”

For Sara Totonchi, executive director of the Southern Center for Human Rights in Atlanta, the ruling carries with it an important acknowledgment by a system that for too long treated minors like the adults they had yet to become.

“I would say this is a big step forward for children,” Totonchi said. “What the court did today is recognize that there is fundamental unfairness in essentially a death in prison sentence for children.”

With a jump in crime in some cities, including Chicago where nearly 20 people were shot, beaten and stabbed to death last weekend, the calls for a major crackdown on crime – including that perpetrated by and against juveniles – has risen among some.

Here, for example, Chicago police have changed hours and assignments to deal with an escalating homicide rate. The department has pleaded with residents to turn in guns as part of a regular exchange program that police hope will quiet the shootings, and Mayor Rahm Emanuel has been out front in trying to decriminalize possession of small amounts of marijuana to free officers to address more serious and violent crime while he proposes to rewrite stiff gun ordinances that have been overruled by the courts.

These moves are part of a wider push against crime that has some experts worried that lawmakers would be pressed to react swiftly and put the brakes on reforms that are starting to relax some of the harsh laws of the 1980s and 1990s.

“If anything the recent spike in juvenile crime proves that tough on crime measures have little or no effect,” said Steven A. Drizin, the head of the Center on Wrongful Convictions at Northwestern University’s Law School and the former supervising attorney at the Bluhm Legal Clinic’s Children and Family Justice Center. “We have some of the toughest juvenile justice laws on the books — automatic transfer at 15, mandatory minimum sentences, gun enhancements, and truth in sentencing, LWOP, all of which apply with full force to juveniles convicted as adults.

“These laws have been on the books for several decades. They have no deterrent effect on juveniles because most do not know about them, they tend to be impulsive decision makers, and because juveniles are being armed by adult gang members to carry out their dirty work.”

If there is an uptick in juvenile crime – and some would caution it’s more hype than reality – Drizin said the blame belongs more with “economic conditions, instability in the drug markets, easy access to guns, and gang warfare than with tough penalties. Toughening juvenile laws is misdirected because it does nothing to the adult gang leaders who recruit and arm juveniles.”

All the more reason that Monday’s court ruling settled anxiety in some circles.

“The most immediate effect [locally] will be on the nearly 100 juvenile offenders who are serving life without parole sentences in Illinois,” Drizin said, adding that most of the sentences handed down under the old law will have to be revisited. “But the Supreme Court’s decision today may require changes to any sentencing schemes in Illinois that automatically mandate sentences for youth and prevent courts from considering youth as a mitigating factor in sentencing.

“There are many such sentences in Illinois — automatic transfer of juveniles to adult court, mandatory minimum sentences for juvenile offenders, 15-20-25 year gun enhancements, ‘truth in sentencing’ for youthful offenders, and life without the possibility of parole of juvenile offenders, to name a few.”

It’s a long list, and Drizin and other legal experts figure the court challenges to other laws, including, he said, “to the application of the ‘felony murder’ doctrine to juvenile offenders — based on the concurring opinion — will no doubt follow from this decision.

Monday’s decision came on the same day the high court gutted Arizona’s controversial immigration law, and rights advocates and conservative groups alike were busy sending out news releases praising and condemning the court’s actions. But mostly the decision on JLWOP was positive, as fears of a retreat to harsh laws that swelled the prison population by some 600 percent over a generation were somewhat eased.

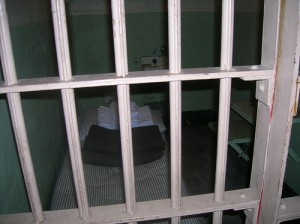

“Kids by the nature have a harder time appreciating the long-term consequences of the decisions they make,” said Shoba Mahadev, a clinical assistant professor at Northwestern’s Children and Family Justice Center, adding that about 80 percent of the juveniles facing life without parole in Illinois were given mandatory sentences . “It is something that anyone would struggle to adjust to for life in prison with no hope to earning your leave.”

“It basically is the third leg of the stool that says you cant be sentenced to life without parole for even a homicide if you’re a juvenile,” said Georgia attorney McNeill Stokes.

In the two precedent cases, Roper and Graham, The U.S. Supreme Court found it unconstitutional, in the first, to sentence juveniles to the death penalty. In the second they struck down life without parole for non-homicide cases.

“It’s a continuation of the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court that recognizes that juveniles cannot be treated the same as adults,” he said.

For Anderson, the decision is perhaps a telling turning point in this country’s justice system. For so long, she said, the system didn’t get that kids were kids – “they’re not miniature adults or short adults, they’re kids.”

Her son, who was accused of being the shooter and was remanded to adult court at 15 and got a mandatory sentence, is now 32. Seventeen years gone – much of it on lockdown – and now she’s hopeful.

“There was such a backlash [against crime] with these laws that treated kids like small adults when my son was convicted,” she said. “We understand that elderly think different, and other parts of government understand that children are different. Why didn’t the courts? Maybe now they will.”

Eric Ferkenhoff is the editor of The Chicago Bureau.

Maggie Lee is a reporter for The Chicago Bureau.

Check out more of JJIE's coverage of the Supreme Court's JLWOP decision:

- UPDATED: Supreme Court Forbids Mandatory Life Sentences Without Parole for Juveniles

- High Court Ruling on Juvenile Life Without Parole Could Impact Many