CHICAGO-- Although gangs are a chronic problem in many urban and suburban areas of the nation, this city included, certain aspects of gang life don’t receive the attention – and therefore the resources – necessary to combat them.

CHICAGO-- Although gangs are a chronic problem in many urban and suburban areas of the nation, this city included, certain aspects of gang life don’t receive the attention – and therefore the resources – necessary to combat them.

In particular, the sexual exploitation of girls by gangs is a serious problem currently facing law enforcement, courts, educators and social service programs across the country, according to a panel that met this week to discuss the issue.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention presented a webinar Wednesday through the Missing and Exploited Children’s Program to address promising practices for targeting the commercial sexual exploitation of girls in gangs. The webinar built on MECP’s June presentation about exploitation by offering organizations and individuals suggestions for internal practices and appropriate interaction with victims.

“The top thing that sexually abused, victimized girls say they want in treatment and in custody is someone to talk to,” said speaker Keith Burt, a retired deputy district attorney and former Chief of the Gang Prosecution Division in San Diego. “Someone they feel they can trust, that they can just talk to.”

Although the speakers acknowledged males and transgender individuals suffer from sexual exploitation by gangs, the victims are overwhelmingly female. Burt also stressed that it’s important to remember these youth are not child prostitutes, but actually victims of horrible sexual abuse imposed by sophisticated perpetrators.

“What we do know about exploiters is that they are very organized,” said Jenee Littrell, who directs the guidance and wellness program at Grossmont Union High School District in San Diego, and has experience working with sexually victimized students. “[Exploiters] are making a lot of money out of this. They have a huge investment in staying ahead of us, and frankly, they’re able to respond and move their systems way faster than we are. So the more that we can do to share our information and stay tight together… then the more responsive we’re going to be able to be in identifying and preventing students from falling into this.”

Alfredo Nambo, the principal at Latino Youth High School in Chicago’s Little Village, has encountered similar problems of general sexual violence among his female students involved in gang life.

“Not only does [sexual violence] happen, but there's not a support system for them to come out and get those services that they need,” Nambo said. “And so they suffer in silence that way.”

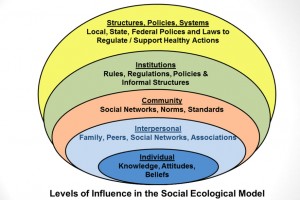

One of the slides from the MECP’s webinar emphasized a social ecological approach for understanding the issue of sexual exploitation of victims by gang members.

Nambo’s frustration with the lack of resources for this “rampant” problem was echoed during the webinar. Other problems include limited access to juvenile records and a lack of options for law enforcement when dealing with the victims.

For example, officers have typically been limited to charging youth as underage prostitutes. But the Illinois Safe Children’s Act, signed by Gov. Pat Quinn in 2010, decriminalized sex-trade involvement for children younger than 18. Deemed unable to consent to their own commercial sexual exploitation, minors are no longer considered perpetrators or juvenile prostitutes. And states across the nation continue to pass legislation against human trafficking.

Some states are even developing progressive programs to address the unique situations of these victims. Burt, for example, mentioned the Hawai’i Girls Court as an example of the judicial system effectively addressing the specific needs of girls who have been sexually victimized by gangs. According to its website, the Hawai’i Girls Court boasts an all-female staff and is “one of the first courts in the United States built on a full range of gender-specific and strength-based programming with a caseload targeting female juvenile offenders.”

The Hawai’i Girls Court is just one example of promising methods for addressing the issue. But beyond big scale approaches like a gender-tailored family court, Burt and Littrell stressed collaboration with victims as a means to better understand their situations and move forward together. In response to a question about what small businesses could do to address sexual exploitation by gangs in their immediate communities, Burt suggested owners could essentially befriend the victims. Instead of seeing victims as aliens or a part of a crime problem in front of their business, Burt said this approach could really make a difference.

“You’d be surprised at what information [you] can get, what little thing may… turn the tide for one of these victims in terms of changing her life,” Burt said.