We’re living in a Golden Age for documentary film — thanks to digital technology, it’s easier than ever to make a documentary, and thanks to the Internet and DVDs, it’s easier than ever to watch one. This is both good and bad — good in that you don’t need a lot of resources to create a documentary, and the cost of watching one can be free, or at least far less than what you would pay for a ticket to a movie theatre. The problem is that a lot of half-baked documentaries are getting made and distributed, and it can be hard for a potential audience member to figure out which documentaries are worth his or her time.

We’re living in a Golden Age for documentary film — thanks to digital technology, it’s easier than ever to make a documentary, and thanks to the Internet and DVDs, it’s easier than ever to watch one. This is both good and bad — good in that you don’t need a lot of resources to create a documentary, and the cost of watching one can be free, or at least far less than what you would pay for a ticket to a movie theatre. The problem is that a lot of half-baked documentaries are getting made and distributed, and it can be hard for a potential audience member to figure out which documentaries are worth his or her time.

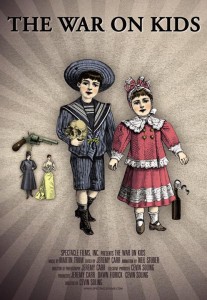

Cevin Soling’s 2009 documentary, The War on Kids, is typical of a lot of the digital documentaries being produced today. It’s neither great nor terrible, but it’s an OK watch if you have an interest in the subject matter and a tolerance for directors who hammer their point of view at you for 95 minutes, without providing a lot of context or research support and no alternative voices at all.

Seriously, The War on Kids often feels like a high-tech sermon intent only on preaching to the choir, and likely to be seen only by those who already agree with its point of view. That’s not entirely a bad thing: sermons can promote group bonding, not to mention getting people charged up and ready for battle, but if you’re looking for a reasoned analysis of the general question suggested by this film — is America engaging in a war on its own kids? — you’ll have to look elsewhere.

The War on Kids starts promisingly enough, with a segment on zero tolerance that traces that policy back to the 1980s, when fear of guns in schools and of so-called “super predator” young people led schools to adopt policies that prescribed automatic punishments like suspensions for kids who brought guns to school. Over the years this zero tolerance concept policy got applied to more and more behaviors, and the punishments got harsher and harsher, leading to the kind of incidents you sometimes hear about on the news (several such clips are provided here), where a kid gets suspended for bringing a Disney key chain to school, or for drawing a picture including a gun. I think we can all agree this is nuts, right? We could use some analysis of the forces that keep such policies in place (hint—it has a lot to do with politics and economics), rather than a parade of similar incidents and talking heads telling us about them, but Soling settles for the latter far more often than he does the former.

A segment comparing schools to prisons, with particular emphasis on security cameras, is also fairly successful, in no large part because a field trip to a correctional institution, and footage captured by school security cameras, provide Soling with something other than talking heads and news clips to put up on screen. Video captured by security cameras during the Columbine High School massacre says more clearly than words that such cameras don’t necessarily increase security (but they do provide great clips for the news).

Even more compelling is footage of a SWAT team raid in a South Carolina high school — as the terrified students are forced to lie down in the hall, at gunpoint and while being menaced by German Shepherds, it appears they are being taken prisoner by some international terrorist gang. The raid found no drugs, but the local superintendent, George McCracken, feels it was justified because “People are trying to figure out – how do you stop this terrible disease of drug addiction” and “the intentions were pure.” It’s one of the more satisfying sections in the entire documentary — to watch a terrifying but fruitless police raid, then see a person bearing some responsibility for that raid speak about it in the third person and with reference to good intentions rather than the reality of the results, is priceless.

Unfortunately, The War on Kids soon degenerates into a diffuse lament about everything that’s wrong with America’s schools (not what’s wrong about some specific schools), from dumb but power-mad teachers to overuse of Ritalin to assigned reading to a school day consisting of an orderly succession of classes.

So many broad statements are made, most without citing any specific research, that it becomes exhausting to try to decide which of the succession of talking heads might be worth listening to, and which are just enjoying their time before the camera. That may be Soling’s intent — to compel you to give up trying to think critically, and just float along with the current of the opinions presented — which is, ironically enough, one of his key complaints about the effects of schooling on children.

Ultimately, The War on Kids fails, beyond the previously cited purpose as a sermon/pep talk for the already converted, because it too often takes the easy way out and assumes what it should prove.

You can read more about The War on Kids on its web page here and watch it for free on YouTube.