Originally appeared in The Chicago Bureau

Originally appeared in The Chicago Bureau

CHICAGO - Violence stalks Chicago’s streets, but when faced with staunchly rising homicide rates that show no sign of ebbing, residents’ capacity to tolerate the state of crime drains by the day.

After Hadiya Pendleton performed with her high school marching band during the presidential inauguration two weeks ago, the King College Prep teen became Chicago’s 42nd homicide victim of 2013 when she was gunned down on Chicago’s South Side – the unintended victim of a gang dispute.

Her death added to a January homicide toll that was the bloodiest since 2002, according to Chicago Police reports, suggesting that despite wide attention to Chicago’s murder woes, shifts in policing strategy and big promises by powerful politicians, there will be no immediate respite to the escalating violence that claimed more than 500 in 2012.

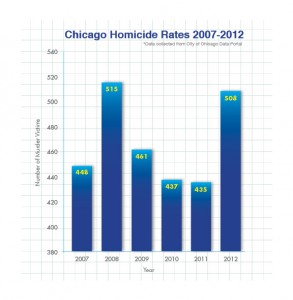

The ups and downs of Chicago’s homicide toll over the past six years/Graphic by Lynne Carty/The Chicago Bureau

Perhaps it’s because Pendleton performed for Obama, or maybe because she starred in an anti-gang public service announcement four years ago (Pendleton PSA) pleading for an end to the chaos, but the nation has embraced this 15-year-old as a symbol and not just another statistic.

As for those who study crime, who write about it and opine about it in Chicago, the nation’s murder capital, the question remains whether it will really matter:

“There is action because of the attention but it is not clear that it will work,” said University of Illinois at Chicago’s Dick Simpson, a known political expert and former alderman who recently studied the nexus of drugs, gangs and police corruption.

The recent moves by City Hall and police brass, for example, are not only an open question for Simpson but do not impress the likes of Tracy Siska, whose organization, The Chicago Justice Project, analyzes and presents on police data and statistics.

“The [high crime, and particularly this sensational murder] is nothing new to Chicago and the faux responses will also be nothing new,” he said. “You will see the police author some new plan to ‘really impact violence’ that has little chance of impacting violence.”

So what will it take to really dent the violence that stains the city and its reputation as a tourist, business and social destination? Siska, who recently analyzed crime and economic data in a column posted on the Bureau, said there will be no unraveling the riddle of Chicago’s high crime until the city’s native cycle of poverty is given real attention and ultimately fixed.

“Nothing,” Siska told the Bureau Friday, “will change until we start talking about changing the horrific economic conditions of these communities and the flow of easily available guns from the suburbs of Chicago.”

With gun control dominating public policy debate at every level of government since the Sandy Hook mass shooting, which claimed 20 children, Pendleton’s death is another source of pressure for the nation’s leaders to deliver on anti-violence promises.

Yet strip away Pendleton’s connection to the president – whose Chicago home is a short distance from the murder scene – as well as the politically charged timing of her death, and she becomes like any other bright-eyed victim of rampant child violence.

The fact is that in many neighborhoods, Chicago’s streets, front yards and parks aren’t safe for children to play, and the reasons for that have only increased despite the youth task forces and anti-violence efforts.

Now, Pendleton’s murder – at once tragic and sensational – has catalyzed communities to call for real action and not just debate. A city inspector charged with analyzing police deployment schemes has suggested the reassignment of nearly 300 officers – something Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel, who announced this week that 200 would shift from desk duty to street patrols and other on-the-ground assignments, has given his blessing.

In addition, Chicago has pounced on anti-gun initiatives with sweeps, gun swaps and new laws. Hoping to clean the streets of so much weaponry, Chicago Police have turned to gun buybacks. They have staged weapons raids and strictly enforced gun laws by tacking on taxes – and potentially more severe sentences – for committing a crime using, or in possession of, a weapon.

Does it count for much?

Pendleton was hanging out with friends after school in a neighborhood park when an unknown assailant shot her in the back on Tuesday. She died at the scene, but another boy was wounded in the leg and transported to the hospital. It’s an all too familiar scenario for those working in violence reduction, and although Emanuel’s news conference following the tragedy has been met with both doubt and support, activists largely agree that crime is a symptom of deeper-set social illness.

Gary Slutkin, founder of Cure Violence, which employs interruption methods to address crime in individual neighborhoods, sympathized with the mayor’s move to do all he could in the immediate wake of Pendleton’s death. However, he said a complete understanding of Chicago’s violence requires viewing crime as an epidemic to be eradicated through a public health, disease control outreach approach.

“Violence feeds on itself,” Slutkin said of analyzing rising homicide rates in recent months. “The problem has been so refractory for so many years that it hasn’t been completely diagnosed, completely understood. It actually operates through our brain processes of copying and of social belonging, and so you have to use the sciences of interruption and behavior change to effectively get reductions.”

He added that although Pendleton’s story certainly deserves the media spotlight, it’s more imperative that solutions to systemic violence are equally addressed.

In many ways, Emanuel and McCarthy, experts are saying, have reached back to the days of Mayor Richard M. Daley and past police bosses like Terry Hillard with an inching toward more, and closer, interaction between the cops who police our streets and those who live here, run the businesses and community organizations who try to prop up the most at-risk residents and neighborhoods.

The push then, mostly in the 1990s and through the early 2000s, was called community policing and was credited, in some circles, with vastly reducing crime – both nonviolent and violent – in Chicago. But pundits love to dismiss politicians and while others are looking for answers in what Emanuel and McCarthy announced, others, including the union, see it as grandstanding by a mayor who has seen problems with the schools, with violence, with city’s finances, among other issues, in his short tenure.

McCarthy can still stand on statistics showing an overall dip in crime to the lowest level in years. But the sensational – the talked-about – statistic is murder, and Chicago ended 2012 as the nation’s bloodiest city. The murder capital of the United States once again.

In fact, so much has been tried in Chicago, and so much has fallen short – including strict anti-gun laws – that the city is frequently pointed to as an example of where the local anti-gun measures have actually proven a catalyst for the high number of killings here. Rather than blunt crime, the pro-gun lobby has said the strict control over guns in Chicago has contributed to the violence.

That, according to other academic, health and law enforcement studies, is nonsense, with anti-gun groups arguing that more guns leads to more opportunity to kill by intention or accident.

Still, for all the high-minded talk, what the conversation for most Chicagoans and most in the nation boils to is this: A 15-year-old majorette, who spoke out against violence, who did well in school, who was very much a part of her family and neighborhood, is gone. There is now a $30,000 reward for anyone who can provide information about her death.

“These were good kids by everything that I learned,” McCarthy said at a Wednesday news conference. “Wrong place at the wrong time.”

Bureau reporters Safiya Merchant and Lynne Carty contributed to this report