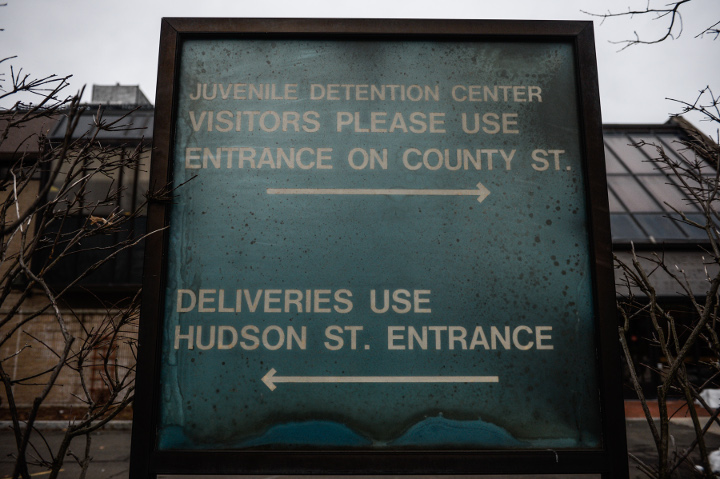

An aged sign at the entrance of State of Connecticut Superior Court for Juvenile Matters and Detention Center in New Haven, Conn. where detainees were once put in isolation before new laws were enacted. (Robert Stolarik for JJIE)

BRIDGEPORT, Conn. — On the third floor of a Romanesque church in Bridgeport there is a shabby office with unreliable electrical wiring and a collection of banged up folding chairs. It’s where Family ReEntry, a social service agency, operates its mentoring programs for at-risk youth. And it’s also where Tina Banas is about to supervise an experimental pilot program for children on probation connecting them to a network of services she could not imagine having existed when she started working as a social worker in the state 30 years ago.

“There were a lot of frustrating times” she said, looking back on her career. “I think there has definitely been a shift in the culture. I talk about it with my colleagues all the time. There’s a real push to get all these collaborations going.”

Banas and her colleague, Kenneth Jackson who was a product of the system and now works to keep children from following in his footsteps, exemplify what has changed in state’s juvenile justice system -- moving away from punitive approaches to ones grounded in therapy and intervention. The focus on this type intervention over jail and detention centers helps to illustrate the revolutionary change in Connecticut’s juvenile justice system over the last decade.

It’s a transformation that is thoroughly detailed in a new report compiled and released today by the Justice Policy Institute and funded by the Tow Foundation. The report says that a mix of legislation, advocacy and political leadership willing to make crucial changes has led to a slew of improvements in the state’s system.

One of the most recent changes is raising the age of teens tried as adults. Sixteen-year-olds in Connecticut were incorporated into the juvenile justice system rather than being tried as adults.

“We talk much more about evidence-based research instead of talking in the language of an-eye-for-an-eye and in terms of punishment that we see in the adult criminal justice system,” said Peter Leone, the acting director of the Justice Policy Institute. “Whether you rely on fiscal argument or moral argument it really makes sense to do things differently, the way Connecticut is doing, and I think the rest of the country can learn a great deal from the Connecticut reforms.”

Leone said Connecticut has incorpoated the idea that juvenile justice should much more closely resemble social services than the policies associated with the adult justice system. Between 2009 and 2011, the total arrests of 16-year-olds dropped by 35 percent. At the same time, serious violent crime amongst the same group fell by 26 percent. In addition, the number of children committed to residential facilities dropped nearly 70 percent between 2000 and 2011.

“Once you became 16 you no longer had access to the services that would help you address the problems,” said Connecticut state Senator Toni Harp. “You’re really investing in young people.”

A hallway leading to the head office at the Family ReEntry Innovation Impact Center in Bridgeport, Conn., that is housed inside the First Baptist Church of Bridgeport. A sign at the front door of the Baptist church shows the reflection of the stained glass of the century old church. (Robert Stolarik for JJIE)

Previously, minors in Connecticut could find themselves in court for what are known as ‘status offenses’— violations such as truancy or possessing alcohol -- that wouldn’t constitute crime for an adult. Many of these cases are now treated more lightly, and rather than landing violators in court, they are often offered alternatives aimed at fixing the problem at the root.

Bill Carbone, executive director of Connecticut’s Court Support Services Division, says this not only is helping the juvenile offenders, it also seems to be keeping younger siblings from entering the system.

“The vast majority of our status offenders do very well in these programs and we don’t see them coming back into the system either as status offenders or as juvenile delinquents,” he said.

For Carbone, part of treating minors as juveniles as opposed to adults was about looking at research and evidence.

“We’re acknowledging what the neuroscience is teaching us,” he said. “The sections of their brains that govern decision making are not fully mature.”

One reason Connecticut has made such progress in recent time, say some, is that there was so much room for improvement.

“In all honesty, we were behind,” Harp said. “And if we are ahead it’s because many states haven’t really taken as thorough a look at their system as we have over the past several years.”

One of the changes proponents are most excited about is the effort to keep minors in their homes and with their families. Carbone says offenders are often missing the structure and support they need at home. Rather than placing them in detention centers, where they’ll likely interact with others who have committed more serious crimes, the reforms try to keep them with their families and in their schools.

“Maybe his conduct is the result of his not going to school and not learning more positive pro-social skills,” Carbone said of a hypothetical offender, “so we need the parents to be more active partners with us.”

For Harp, too, education is one of the most important facets in keeping young people engaged and on-track. Racial inequities in the justice system are still severe, and she cites improving schools and looking at alternatives to the traditional system as possibilities for improving these disparities.

“We’ve got to look at ways to improve kids staying in school, making sure schools are places where kids feel comfortable and can succeed,” she said.

Some schools have kept a zero-tolerance policy, and are not willing to deal with problems in-house instead of involving the legal system. Similarly, not all parents are on-board with the programs. Home intervention can mean one home visit a day or it could mean three, and some parents are not welcoming of that kind of intrusion.

Still, advocates like Carbone are dedicated to doing whatever is possible to keep kids out of the courts as much as possible.

“The court activity can be counterproductive,” he said. “It sends a message that you’re bad, you’re delinquent and they tend to live up to societal expectations.”

The First Baptist Church sits on top of hill in the hardscrabble town of Bridgeport. A small sign in the lobby of the castle-like structure greets visitors to Family ReEntry. A cavernous wooden stairwell that creaks with each step leads to the 30-foot high vaulted ceilings of the sanctuary cast in an eerie gloaming from stained glass windows.

Above that there is a sparsely furnished room with a few desks and fold-out cafeteria tables doubling for conference space. Stacks of pudding, chocolate and vanilla, sit across from a corkboard with pictures of children out with mentors on trips, laughing as they try to water ski on Lake Zoar or wander in the Maritime Center.

Above that there is a sparsely furnished room with a few desks and fold-out cafeteria tables doubling for conference space. Stacks of pudding, chocolate and vanilla, sit across from a corkboard with pictures of children out with mentors on trips, laughing as they try to water ski on Lake Zoar or wander in the Maritime Center.

On the fourth floor, Kenneth R. Jackson keeps his office, but he says his is not a nine-to-five job. He says teens in the neighborhood come to visit him at his house at all hours of the night, asking him for advice or just looking to talk. Sometimes he pulls over and hops out of his car to break up a fight. For Jackson, the mentoring program he runs and the interventions he works on aren’t dry numbers in an academic report. It is a mission of redemption.

Every day he is reminded of that mission when he goes to take his two dogs -- Chaka and Thunder -- for a walk, when he gets to Connecticut Avenue and 5th Street. It’s the corner where he killed a man -- shot him in the temple -- and not far from where his son, who sits in prison now, killed someone when he was only 15.

“I might not even be alive when he gets out,” said Jackson, 58. “Thats my driving force doing this, in the name of my friend whose life I took and my son’s life which I ruined. I want to make it right. I ruined him. I created the generation behind me that ended up in prison.”

Jackson said he understands that on paper things have improved, and that he is happy to see intervention programs are being encouraged over confinement.

“It’s hard for me to say it’s getting better when I look out my window and see what’s going on in my neighborhood,” he said. “The gangs, the violence, the poverty. The numbers say things are getting better but I live in an area where people can’t find work. I don’t care how much money they put into the system or how many reforms there are, they can’t do it with us out there helping to clean up the mess we made.”

This story was produced by JJIE's New York Metro Bureau.

The Tow Foundation is a funder of the JJIE.