How many young people confined in the juvenile justice system need treatment for mental health and substance problems, and how well are those needs being met? The Survey of Youth in Residential Placement (SYRP) – the first-ever national survey of youth in juvenile custody – offers a detailed, if slightly dated, window into these issues using information obtained from young people themselves. See related story here.

Conducted in 2003, SYRP gathered data from a nationally representative sample of youth housed in state and local juvenile facilities. Not released until 2010, the SYRP data show that many young people confined in juvenile facilities had experienced trauma, and most suffered with one or more mental health or substance abuse problems. Yet many confined youth received no counseling in their facilities. Just as troubling, youth with the most severe needs were no more likely than other youth to receive counseling, and they were less likely than other youth to describe as helpful any counseling they did receive.

Enormous Trauma and Need

SYRP found that 30 percent of confined young people had experienced sexual, physical, or emotional abuse, 67 percent had seen someone killed or severely injured, and 70 percent reported that something bad or terrible had happened to them. Only 15 percent reported no trauma incidents in their past.

A large share of juveniles in custody reported behaviors that make it difficult to succeed in a conventional classroom, such as having a hard time paying attention in school (45 percent), having a hard time staying organized (40 percent), and being unable to stay in their seat (32 percent). Surprisingly, all three behaviors were reported at a higher rate by girls than by boys.

Anger problems were also rampant among confined youth: 68 percent reported being easily upset, and 61 percent said they lost their temper easily. Here, too, girls were more likely than boys to report problems.

Signs of more serious mental illness were also widespread. One in six confined youth suffered hallucinations, for instance. One fourth had elevated symptoms for depression, and substantial percentages reported having suicidal thoughts (28 percent), feeling that life was not worth living (25 percent), or wishing they were dead (19 percent). Girls were far more likely than boys to report each of these symptoms. And, alarmingly, 44 percent of confined girls reported that they had attempted suicide, compared with 19 percent of confined boys.

Two-thirds (68 percent) of juveniles in custody reported an alcohol or drug problem in the months preceding custody: 49 percent reported drinking many times per week or daily, and 64 percent reported taking drugs this frequently.

Many Denied Counseling

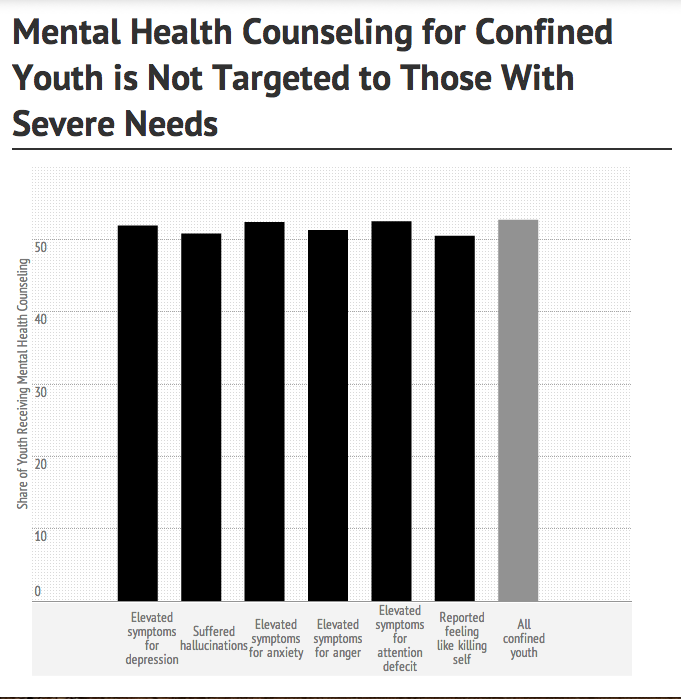

Despite these grave and widespread needs, barely half (53 percent) of all youth included in SYRP reported receiving any mental health counseling in their facilities, and just 51 percent reported any substance abuse counseling. Youth in commitment programs – those who had already been adjudicated and placed into treatment or corrections facilities – were twice as likely to receive counseling than youth in temporary detention centers (61 percent vs. 30 percent), but a substantial share of youth in all facility types did not participate in counseling.

Moreover, SYRP data reveal fundamental mismatches between the youth who most needed counseling services and those who received them. For instance, youth with elevated symptoms for depression, anxiety, hallucinations, and anger were all less likely than youth with fewer symptoms to participate in mental health counseling. Likewise, youth reporting suicidal thoughts were less likely to receive counseling than youth who didn’t.

However, just 40 percent of youth who reporting frequent drug or alcohol abuse in the months before custody and received substance abuse counseling services said that the counseling was “very helpful,” compared with 48 percent of youth with less serious substance abuse problems who received counseling. Youth with more numerous mental health symptoms were also less likely to find counseling helpful than youth with fewer symptoms.

Harsh Discipline and Unfair Treatment

Survey responses also suggested that conditions inside many juvenile justice facilities were not conducive to effective treatment. Thirty-eight percent of surveyed youth said they were afraid of being physically attacked in their facilities, and 35 percent said that staff used force against youth when it wasn’t necessary. Nearly half of the youth surveyed indicated that staff in their facilities conducted strip searches, and one-fourth of the youth reported being held in solitary confinement.

Youth confined in secure correctional facilities were far more likely than youth in other facility types (detention centers, residential treatment units, wilderness camps, or community-based facilities) to report these kinds of dangerous conditions and harsh disciplinary practices, which can be especially problematic for youth with histories of trauma or mental illnesses.

A 2010 Justice Policy Institute research review on trauma-informed care for court-involved youth found that “Confinement has been shown to exacerbate the symptoms of mental disorders, including [post-traumatic stress disorder], and the act of processing youth into juvenile custody (for example, using handcuffs, searches, isolation and restraints), as well as the risk of abuse by staff or other youth can be traumatizing.”

“In particular,” the report stated, “characteristics of correctional facilities, such as seclusion, staff insensitivity or loss of privacy, can exacerbate negative feelings created by previous victimization, especially among [post-traumatic stress disorder] sufferers and girls. Youth in correctional facilities are frequently exposed to verbal and physical aggression, which can intensify fear or traumatic symptoms.”

In addition, SYRP youth complained of unfair treatment in their facilities: 38 percent reported that staff were disrespectful, 30 percent said staff were mean, and 50 percent said that staff sometimes punished youth even when they didn’t do anything wrong. Those perceptions are troubling in light of evidence suggesting that young people’s perceptions of fairness within a facility and their positive relations with staff may directly influence their success following release.

Problematic Treatment Practices

SYRP also reported data on the policies and practices of juvenile facilities regarding mental health and substance abuse treatment. A 2010 summary of SYRP findings published by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention concluded that “Current mental health services for youth in custody still fall far short of key recommendations for practice.”

More than one-fourth of confined youth nationwide were held in facilities that did not routinely screen all youth for suicide risk, the study found, and more than half were in facilities that did not screen or assess all residents for mental health needs. In addition, suicide and mental health assessments were often completed by unqualified staff, and nearly 9 of every 10 confined youth nationwide resided in facilities that relied on unlicensed staff to deliver some or all counseling services.

Funded by the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, the SYRP was conducted by the Westat research corporation and included a nationally representative sample of 7,073 young people age 10-20 and housed in state and local juvenile facilities. The results were weighted to provide accurate estimates of the national population of young people in custody. SYRP data were collected through anonymous, computer-assisted audio interviews, a method used to accommodate subjects with poor literacy skills while also preserving the respondents’ anonymity.

Statistical Note: All percentages in this article reflect the share of SYRP youth who provided answers to the specific questions cited. A substantial share of SYRP youth did not answer questions regarding alcohol and drug abuse, and about substance abuse counseling.

For more information:

A 2010 Summary of SYRP results published by the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention can be found at: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ojjdp/227730.pdf

Or, readers can learn more about the survey and analyze the SYRP data themselves by visiting: https://syrp.org/default.asp.

This series is part of an ongoing collaborative with the Center for Public Integrity.