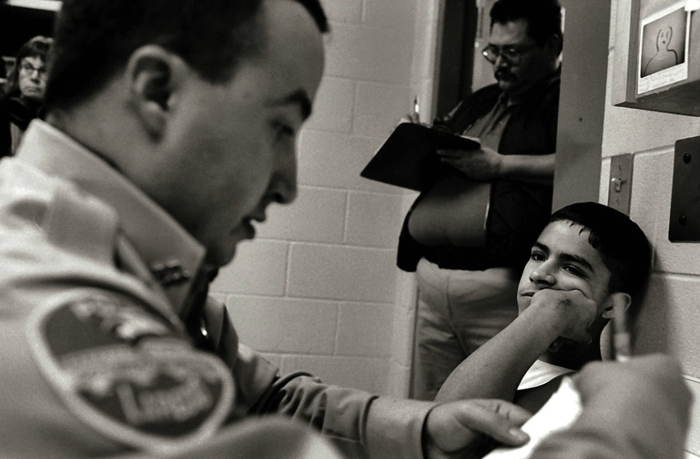

From the Steve Liss Collection / The Chicago Bureau

Reintroduced in Congress this March, the Youth PROMISE Act has been advertised as a common-sense, cost-saving measure to reduce the U.S. prison population by focusing on youth violence prevention and intervention.

But some juvenile justice experts express concern about the impact the Act could have on policing in black and Latino communities and how effective the bill could be in the absence of broader structural change.

While sympathetic to the Act’s stated goals, these experts say that the legislation is likely to achieve only limited results in the face of pervasive police misconduct, economic inequality and racism.

While sympathetic to the Act’s stated goals, these experts say that the legislation is likely to achieve only limited results in the face of pervasive police misconduct, economic inequality and racism.

Potential for Police Abuse

The Act would provide federal funds to communities that establish local councils to assess the needs of at-risk youth and implement anti-violence strategies. Section 102(d) of the Act specifically prohibits information collected by these councils, which would include law enforcement personnel, from being used in criminal investigations and prosecutions.

Andrea Lyon, director of DePaul University’s Center for Justice in Capital Cases, doubts, however, that such restrictions will be observed by the Chicago Police Department.

“There’s plenty of really good police officers, but there’s a cadre of police officers that nobody will do anything about that hide exculpatory evidence, intimidate witnesses, do all kinds of stuff, and are viewed by the citizens, particularly in poor areas, as the enemy,” she says.

The Chicago Police Department did not respond to requests for comment.

bbcworldservice / Flikr

Chicago Police Department

John Márquez, an assistant professor of African American and Latino/a studies at Northwestern University, shares Lyon’s skepticism. In the early 1990s, Márquez says, he worked as a violence interrupter in Houston with a government-sponsored program formerly called Gang Activity Prevention, which is similar to Chicago’s Cure Violence program.

During his time there, one of his friends was murdered by a GAP co-worker, who was later convicted.

“The police were very much involved with the GAP program and they began to use our employment status as a way to gather information about the things that were transpiring, so that police used the GAP program as a way to arrest this guy,” Márquez says.

Now involved with Chicago’s Violence Prevention Committee, Márquez continues to participate in anti-violence initiatives, hoping to shape the conversation. But he worries that such initiatives may also function as mechanisms of social control in black and Latino neighborhoods.

“It’s often a frustrating conversation for me to participate in, primarily because my message is always that we don’t need funds, or we don’t need the state to have conversations amongst ourselves in violence-stricken communities about why we are so violent towards one another,” Márquez says.

“And,” he adds, “one of the fears that I have is that by being able to manage these types of conversations, the state also uses that as an extra form of surveillance or as part of the law enforcement apparatus itself.”

Rob Vickery, the program director for juvenile justice programs at the Chicago-based advocacy group Illinois Collaboration on Youth, is more optimistic about the effect the Youth PROMISE Act will have on policing.

“If anything it’s probably a more positive youth-oriented framework for police to get trained in and use,” Vickery says. “I work with a couple young men who, when they tell me their stories of interactions with the police, they’re treated roughly, unfairly, on a regular basis. And I don’t think that’s helping us as we try to address youth violence.”

The continuation of these practices would complicate the implementation of PROMISE Plans by the local councils.

“Look, any program you design can boomerang,” Lyon says. “And if this program becomes something that looks like and acts like a way of the police getting inside information on drug dealing or other kinds of criminality as a way to effectuate arrests, it’s going to fail.”

The Limits of Community Engagement

Lisa Jacobs, vice chair of the Illinois Juvenile Justice Commission, the Chicago-based state advisory board, says that the potential for net widening is best addressed at the local level.

A September 1999 bulletin from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention describes net widening as a phenomenon in which a program intended to divert youth from the juvenile justice system ends up drawing more youth into the system than would have occurred otherwise.

“I think we’re always concerned about net widening when we work on juvenile justice issues,” Jacobs says. “And the best way to prevent that is again at the local level and again making sure that we’re building opportunities to divert kids from the formal juvenile and criminal justice systems and to again get that support they need in the community.”

Vickery agrees, saying that the councils of local stakeholders are one of the bill’s strong suits.

“I think local communities probably know best what their needs are and what some good solutions would be,” Vickery says.

Márquez, for his part, emphasizes that communities of color must mobilize independently of the government. Wary of what academic and activist Andrea Smith calls the “grassroots-industrial complex,” he says that government programs in black and Latino communities since the 1970s have co-opted local dialogues and foreclosed radical possibilities.

“The neoliberal state really wants to institutionalize everything,” Márquez says. “It’s like, ‘Well, if you’re saying that injustice exists, we’re going to launch a new program to address that for you.’ They do that spin over and over again.”

Márquez says that this co-optation has discouraged critical discussions of race. In his work with Chicago anti-violence initiatives like the Violence Prevention Committee, he has noticed a deep reluctance to address the racial and gender dimensions of a conflict in which black and Latino males are the primary victims and victimizers.

“It’s so glaringly obvious that there is a racial dynamic to this issue,” Márquez says. “And if we can’t speak about the very condition that we are trying to organize against, then we’re just playing politics, basically.”

Ebony DeBerry, chair of the Violence Prevention Committee, says in an e-mail that the initiative is still evolving.

“The Violence Prevention Coalition (VPC) addresses issues that [are] brought up by the community residents in Rogers Park,” DeBerry writes. “The VPC is in the process of identifying a new issue, as this is only the second campaign the Violence Prevention Coalition has ever embarked on since its restructure. To look at violence through a wider lens is the VPC mission. The topics of race, education, poverty, housing, and mental health support are causes that often times lead to violence, and the very Foundation from which the VPC looks to pick its issues.”

Intervention programs can also disempower the populations they claim to uplift, Márquez says. As part of the GAP public speaking team in the early ’90s, Márquez and a friend paralyzed in a drive-by shooting spoke to audiences of predominantly white businessmen, standing before them as “emblems of chaos and pathology” and asking them to cut checks for the program.

“The more we engaged in that practice, the more I would go up and spin this narrative and tell people about how savage we are, the more I felt disempowered,” Márquez says.

Much like race, economic inequality is often overlooked by intervention programs, says Tracy Siska, executive director of the Chicago Justice Project. He says that while the programs supported by the Youth PROMISE Act will likely have some positive effects, they are not a long-term solution.

“I think that any kind of intervention program that doesn’t deal with the underlying economics of the issue, of the communities, is at best going to have limited impact,” Siska says.

Community engagement, by itself, can only accomplish so much, he says.

“I don’t think it makes much of a difference how much they partner with the community,” he says. “They’re still only dealing with the surface issues and not the root causes, and that’s going to be any of these intervention programs. That doesn’t mean they’re bad, it just means they’re going to have a limited effect.”

Root Causes

Siska has emerged as one of the most vocal critics of Cure Violence, formerly known as CeaseFire, and its promoters in the political and media class.

In a five-part blog series in 2008, Siska argued that the program’s claimed successes in Chicago could not be validated by a Northwestern University evaluation due to intervening variables. Siska maintains that there has been no convincing social science research since then to support Cure Violence’s claims, saying that “it’s very hard to validate a negative,” in this case violence that did not occur.

Northwestern political science professor and Institute for Policy Research fellow Wesley G. Skogan, one of the authors of the 2008 evaluation, disputes Siska’s assessment. He says that the team accounted for external variables by analyzing three streams of evidence from control and comparison neighborhoods: long-term trends in monthly crime rates, shifts in gang homicide networks and the mapping of crime hotspots.Siska’s assertions are “flat-out inaccurate,” says Josh Gryniewicz, Cure Violence’s communication director, who points to evaluations of the Cure Violence model in Baltimore and Crown Heights, Brooklyn that support Skogan’s findings. He adds that Cure Violence has made The Global Journal’s international Top 100 NGOs list two years running, ranking ninth overall in 2013. On both the 2012 and 2013 lists it ranked first among conflict resolution organizations.

Despite questions about their effectiveness, intervention programs like Cure Violence have enjoyed overwhelmingly positive media coverage.

“That’s a solution that makes sense to them because no one wants to deal with the underlying issues, which are racism, classism, the complete devastation and total ignoring of these communities,” Siska says. “And most reporters are white.”

Siska calls for increased investment in schools and community-based institutions. For Márquez, though, economic investment only goes so far. The psychosocial effects of racism and colonialism must also be addressed.

Racism was central to the development of Chicago’s gangs, he says. He wrote in anAmerican Quarterly article last September that the first black and Latino “gangs” emerged in the 1940s and 1950s to defend their communities from white ethnic gangs that violently enforced segregation.

Drawing on the work of Frantz Fanon, the French-Algerian anti-colonial theorist, Márquez argues that oppressed peoples internalize their own dehumanization, coming to view their own lives and the lives of their peers as without value. This “racial state of expendability,” coupled with the inability to challenge their oppressors directly, leads to crippling intra-group violence that delays liberation.

“Fanon really talks about these fits of what he calls inter-tribal warfare and violence toward peers because people don’t know what else to do with that rage derived from expendability,” Márquez says.

This critique unsettles the assumptions behind intervention programs.

“It almost makes violence prevention a kind of schizophrenic practice, primarily because you’re asking if the state itself is responsible for the colonial segregation that has produced violence, how then therefore can the state step in to be the remedy for that violence?” he says.

A New Model

Siska says he has no confidence that politicians will address underlying issues like racism and classism anytime soon. He points to Chicago’s recent school closings, which he says will “absolutely” exacerbate violence, as one example. Communities must alter their voting habits if anything is to change, he says.“Well, I think that you can look at the support of tax increment financing districts and where that tax, TIF money gets spent, and how it gets spent,” Siska says. “And then each community should look at how their alderman or their state rep or whoever it is votes on those things and whether or not that actually helps their community or not. And if it doesn’t, vote them out.”

Márquez locates hope for the future in the affected communities themselves. He notes that gangs, often blamed as the root cause of the problem, also present some of the solutions.

“I think that if you look at the history of Chicago, the history of any city in the country that has experienced these types of conditions, you’ll see that the only social units that have been able to deter ghetto violence or deter gang violence have been gangs,” Márquez says.

In the 1960s, for example, Chicago gangs influenced by the anti-colonial politics of the time entered a truce brokered by Black Panther Party activist Fred Hampton, who organized a “rainbow coalition” of blacks, Latinos and working-class whites before his controversial 1969 death at the hands of the FBI and Chicago police. These gains were lost by the 1980s, when the crack epidemic fueled a massive rise in gang violence.

While Márquez cautions that no historical model can be repeated, he emphasizes the need to build coalitions across racial lines and open up the conversation to the body politic at large. Ultimately, he says, communities must act on their own behalf. To this end, he quotes Jose Cha Cha Jimenez, founder of the Young Lords, the Puerto Rican nationalist group.

“The only people who can save us from us is us,” he says.