gmpicket / Flikr

Neighborhood in South Jamaica, Queens in New York City.

NEW YORK--The George Zimmerman verdict hasn’t just evoked feelings of disappointment and betrayal among many residents in New York City, it has provoked action. Across New York City yesterday some attended rallies and others joined protests and marches on behalf of Trayvon Martin and his family.

But here, near the Baisley Pond Houses in South Jamaica, Queens, where Sean Bell and his friends grew up, people haven’t been raising their voices – they’ve been pulling out their guns.

Early on the morning of Nov. 25, 2006, Bell and his friends Trent Benefield and Joseph Guzmann were shot in a fusilade of 50 bullets fired by members of an NYPD unit investigating Club Kalua, where Bell had celebrated his bachelor’s party. Bell, 23, was killed in the shooting. He was to be married later that day. Both Benefield and Guzman were seriously injured.

Three of the five detectives involved in the shooting were indicted. They were found not guilty.

The Bell shooting, much like Martin’s, became about more than a single death. Bell’s death at the hands of the NYPD transformed into a civil rights movement across the city, especially here in South Jamaica, Queens, where Bell grew up.

Now, after the Zimmerman acquittal Saturday night, gunshots along the avenues have been commonplace, shots fired in protest and rage, according to locals. Sunday night, residents said they were concerned not only about a lack of hope here after the verdict, but also a contempt for authority that seems to be spreading among black youth.

Clifton Henderson, 30, said he heard gunshots along his street on both Saturday and Sunday, a sign that, “they’re not respecting the cops no more.”

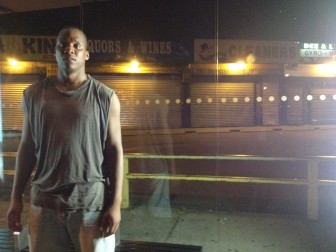

Christopher Dell / New York Bureau/JJIE

Clifton Barrow, 30, waits alone at a bus stop near Baisley Pond Park, mere hours after finding out the news of the Trayvon Martin/George Zimmerman verdict.

“The anger from this trial is going toward cops or anyone that’s white,” he said. “I’m not saying there’s going to be riots or anything but they simply don’t care about the consequences anymore.”

Nearly seven years removed from Bell’s killing – and the subsequent acquittal of three of the five detectives indicted in the shooting -- many residents here feel like it’s happening all over again: Different name. Same result. Sean Bell, 2006. Trayvon Martin, 2013.

Residents said they don’t take any solace in the legal complexities that defined the Martin case, all they see are innocent black teenagers unarmed yet gunned down, only to see the killers walk. Bell on his wedding day; Martin with a bag of Skittles in his hand, Henderson said.

Curtis Peterson, 44, shook his head with disappointment when asked what he told his children upon learning about the Zimmerman acquittal. Peterson sat calmly in the front seat of his minivan - the plastic, silver cross on his dashboard slowly swaying back-and-forth - outside of the Dunkin Donuts on Rockaway Boulevard while his two sons, Marcus and Gary, poked their heads from the back seat, intent on hearing their father’s opinion but seeming too young to understand the gravity of the conversation.

“I tell them,” Peterson said as he motioned toward the back seat. “I tell them they gotta stay straight and stay out trouble, stay out of the neighborhoods where you know something might just go wrong. You walk down the wrong street at the wrong time you’re liable to get arrested for who knows what. Stop-and-Frisk is one thing, but this just isn’t right. America somehow seems to accept it just as it is, though.”

For decades, Peterson said, it was “white people who would feel in danger” when walking into predominantly black neighborhoods. But now, ironically, the tables have turned, he said.

“Right now some white person can walk straight down this block and won’t get touched,” he said. “But if we walk down to Howard Beach right now – and by we I mean us – we better be able to get in the car and get outta there quick.”

Henderson said Martin’s death hits closer to home for residents from South Jamaica, where the memory of Bell and how he was killed is still fresh.

“It was a personal thing,” Henderson said. “I say the anger from the verdict will pass over after a while, but right now people aren’t trying to take things lightly.”

The streets in South Jamaica were as empty as an unloaded gun on Sunday night and into Monday morning, minus a few stragglers coming in and out of their apartments on Rockaway Boulevard and heading down to the nearby bodega or Dunkin Donuts.

One of those residents, Walter Dixon, 20, has lived in the area his whole life. He attended Hillcrest High School and now works security at JFK Airport. Dixon was only 13 when the Bell shooting happened, but he remembers tensions being high between South Jamaica residents and NYPD in its wake.

Nothing has changed this time around, he said.

“Everybody is upset, they feel like justice hasn’t been served,” said Dixon, who added that he has been weary of violence breaking out since the verdict was announced. “I’ve seen people talking to cops. I’ve heard gunshots. Whether it’s on the street or even on Facebook, people are pissed off. Not everybody forgives and forgets.”

Henderson said that black teenagers and young men need to take extra care when walking around in public.

“They have to be careful with what they do now,” he continued. “Say a cop gets involved – they’re not going to have a case, it won’t work out for them. That’s what the Trayvon Martin case shows us”.

Bell and Martin might have national recognition, but others in the city have met similar ends, most recently last December when Ramarley Graham, 18, black and unarmed, was shot and killed in the bathroom of his Bronx apartment by a narcotics officer.

The officer’s case never made it to trial. It was thrown out on a technicality.

“If you think about it, every time we walk out onto the street it’s liable to happen,” Peterson said. “Cops shoot kids in the back all the time and say it’s justified. Every time you turn around black people are getting killed.”