jshapins / Flikr (license: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.0/)

From The Chicago Bureau

Community supervision aimed at high-risk offenders, as well as mandatory evidence-based programs, have the potential to curtail the U.S. correctional system which has seen more than a 700 percent increase in size, the Vera Institute of Justice has found in a new report.

The term, ‘community corrections,’ refers to the supervision of those in the criminal justice system but not physically incarcerated, such as defendants on parole or probation. These individuals may directly report to a correctional officer or be involved in community programs like work release whereby they carry out the rest of their sentences in a productive setting.

In 2009, roughly seven out of 10 offenders – 5.1 million people – were under community supervision, a number that has stayed constant.

“When adequately resourced and carefully planned, community supervision can be an effective response to criminal behavior for both justice-involved individuals and communities,” according to the Institute’s Center on Sentencing and Corrections report.

Through case studies of correctional systems in states like California, Delaware and Georgia, the center found that transforming community supervision practices to allocate resources such as staffing and funds for evidence-based programs from low-risk to high-risk offenders would allow better use of limited public safety dollars.

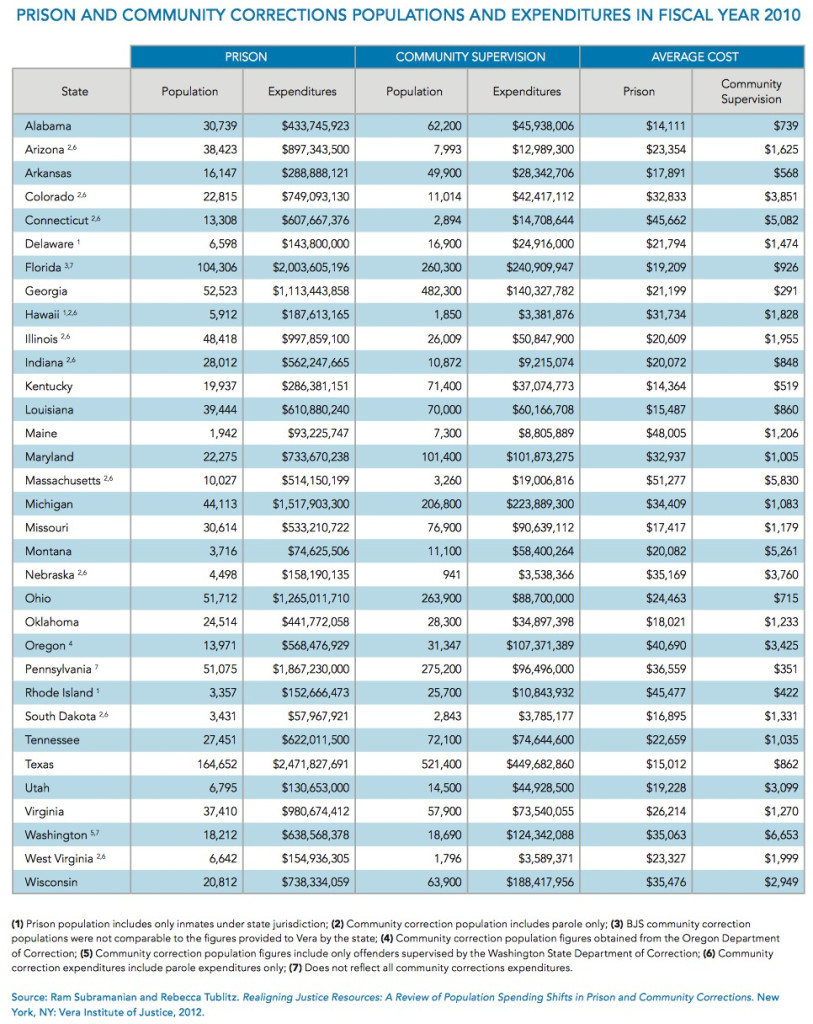

Currently, the estimate for total state spending on corrections is $52 billion per year, only a small fraction of which is used for community corrections due to its low cost. In some cases, it is even less than 5 percent of average cost per inmate kept in prison.

But many times, the low cost is the result of “large caseloads” and “a lack of key services,” thus demanding that more resources be allotted for community supervision.

In particular, evidence-based programs should be made mandatory and developed more fully with the goal of a “practical reality,” — such as public safety — as explained by the National Institute of Corrections, a source of the Center’s report.

An example of a state that has implemented such a program is Arkansas, who in 2011 mandated parole and probation officers to create individualized plans for all offenders, according to whether they were classified moderate- or high-risk by a risk assessment tool. This tool, the Center reported, also determines appropriate intervention measures for “specific criminal risk factors, such as antisocial thinking.”

However, to avoid a “return to the days of ‘nothing works,” wherein policymakers give up on the goal of a functional and realistic answer to the problems in the correctional system, the suggested policy changes like re-allocation of resources based on evidence-based programs must receive both political and fiscal support to succeed, wrote Peggy McGarry, the Center’s director.