The suburban street where I have lived the past two years has about 45 houses, not counting cross streets and cul-de-sacs. I imagine that there are about 250 folks in these houses. I see families driving down the street and couples walking their dogs. I think I have met about 12 of them. That’s not many out of 250. Six of those live next door or across the street. If someone who didn’t live there was walking down the street or sitting in a driveway I would have no way of knowing. We have a neighborhood watch sign, but I don’t think anyone is on patrol or doing anything remotely organized.

The suburban street where I have lived the past two years has about 45 houses, not counting cross streets and cul-de-sacs. I imagine that there are about 250 folks in these houses. I see families driving down the street and couples walking their dogs. I think I have met about 12 of them. That’s not many out of 250. Six of those live next door or across the street. If someone who didn’t live there was walking down the street or sitting in a driveway I would have no way of knowing. We have a neighborhood watch sign, but I don’t think anyone is on patrol or doing anything remotely organized.

It’s funny, considering that I speak to people often about community based conflict transformation, restorative justice and how they can be more involved in settling their own problems. I attribute the lack of physical community in my own life, at least in large part, to architecture, particularly suburban development. Each house is its own little manor, with clear cut boundaries and no real common spaces. We don’t even have sidewalks. Of course we don’t have many conflicts either, which is terrific, but I might be willing to have a few in exchange for some neighborly fellowship.

When we consider crime prevention strategies neighborhood, involvement is important. Sociologists talk about two ways that societies regulate themselves: formal and informal social control. The first is state sanctioned, so it includes police, courts, schools, and laws that proscribe undesirable behaviors. It’s why panhandling in certain towns or sections of cities is a crime.

The informal kind counts on regular people stepping forward to enforce social norms. The most developed strategy has been involving citizens in neighborhood watches and encouraging them to call the police when they see suspicious activity. The idea is to use the informal kind of control to trigger a formal response. A less well developed approach is to get people involved in solving their own issues. This could be a grandmother who scolds the kids selling drugs in front of her house, threatening to call their mommas on them (a far worse threat than calling the cops perhaps). These are the kinds of solutions that require an investment in, and knowledge of, our communities, and they aren’t easy to prescribe. They call on us to actually know our neighbors, or to be willing to get to know them.

The informal kind counts on regular people stepping forward to enforce social norms. The most developed strategy has been involving citizens in neighborhood watches and encouraging them to call the police when they see suspicious activity. The idea is to use the informal kind of control to trigger a formal response. A less well developed approach is to get people involved in solving their own issues. This could be a grandmother who scolds the kids selling drugs in front of her house, threatening to call their mommas on them (a far worse threat than calling the cops perhaps). These are the kinds of solutions that require an investment in, and knowledge of, our communities, and they aren’t easy to prescribe. They call on us to actually know our neighbors, or to be willing to get to know them.

Government has understandably preferred neighborhood watch efforts, but without the balance of more direct involvement we risk creating a climate of suspicion and fear, a state that can lead to tragic events like the killing of Trayvon Martin.

Sarah Goodyear, writing for The Atlantic Cities, contrasts the two informal approaches in a recent article, “A New Way to Understand ‘Eyes on the Street.” The first is National Night Out, organized by National Association of Town Watch, and aims to “promote involvement in crime prevention activities, police-community partnerships, neighborhood camaraderie and send a message to criminals letting them know that neighborhoods are organized and fighting back.”

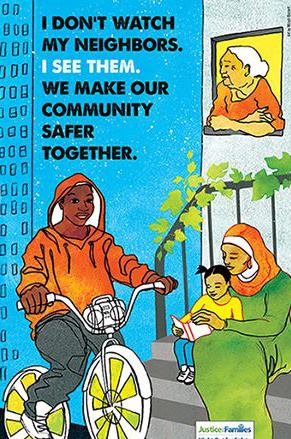

The second is Night Out for Safety, Democracy, and Human Rights, sponsored by Justice for Families. You can tell by the name this is a different approach. They clearly state how their approach differs from National Night Out, where “police encourage residents to ‘take back their streets’ by acting as ‘eyes and ears’ for the police.” Instead, Justice for Families wants to remind people that they also have “hands, hearts and minds” and that they can, instead of looking for enemies to turn in, turn toward their neighbors to find collaborative solutions to safety and other issues.

For me the second approach is far more appealing. I would rather look for ways to build community with everyone than be on the lookout for those who don’t belong. Building an inclusive community seems like a better path to safety than creating enclaves. The first means doing our part to help the government control us more effectively, while the second means stepping up to deal with problems before they become too serious. Both events are scheduled for August 6 this year. I know which one I’ll support. We’ll still call the police if we need to, but in the meantime we’ll be tearing down walls instead of building them.