Annie E. Casey Foundation

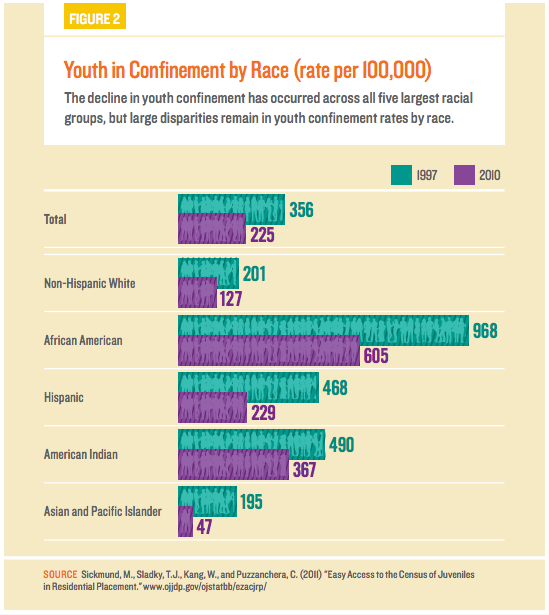

Figure from the Annie E. Casey "Kids Count" 2012 report showing youth in confinement by race. Casey Foundation

In a bid to decongest the nation’s overpopulated prisons, the Obama administration has proposed leniency for certain drug cases, a move with uncertain consequences for juvenile inmates.

The president’s new Smart on Crime initiative has received national attention since Attorney General Eric H. Holder announced the policy at the American Bar Association’s annual meeting in San Francisco on Monday.

The initiative – highlighted by an easing of mandatory minimum sentencing laws for low-level drug cases – could help reduce the booming prison population. But it’s unclear what impact that will have on the country’s juvenile incarceration rate, the highest of any industrialized nation.

“This is all great language, but in terms of what reforms (Holder’s) proposing and how they will reduce juvenile incarceration – it’s an open question,” said Antonio Ginatta, Human Rights Watch advocacy director of the U.S. Program . “The real action needs to occur in state legislatures and in Congress.”

“Long story short, he identifies the right issues, but I don’t know if he has all the tools necessary to make the changes.”

Under Smart on Crime, prosecutors would be ordered to omit the quantities of illegal substances in indictments for low-level drug cases. The program would also promote alternatives to jail for low-level, non-violent crimes and improve reentry programs in order to reduce incarceration and recidivism rates.

CNN

Screenshot from CNN coverage of Attorney General Eric Holder speaking at the American Bar Association's House of Delegates in San Francisco.

“As the so-called ‘war on drugs’ enters its fifth decade, we need to ask whether it, and the approaches that comprise it, have been truly effective,” Holder stated in his speech on Monday. “With an outsized, unnecessarily large prison population, we need to ensure that incarceration is used to punish, deter, and rehabilitate – not merely to warehouse and forget.”

According to varying estimates, the prison population has swelled by 600 to 700 percent over the past 30-some years. Get-tough-on-crime laws originating in the 1980s reduced rampant crack and gang wars, but organizations such as the juvenile justice nonprofit W. Haywood Burns Institute have argued the harsh laws of the period targeted mostly people of color and youth used as runners for drug dealers.

In fact, Holder’s speech specifically mentioned youth violence, stating the need “to better understand, address, and prevent young people’s exposure to violence,” as well as “those zero-tolerance school discipline policies that do not promote safety, and that transform too many educational institutions from doorways of opportunity into gateways to the criminal justice system.”

In fact, Holder’s speech specifically mentioned youth violence, stating the need “to better understand, address, and prevent young people’s exposure to violence,” as well as “those zero-tolerance school discipline policies that do not promote safety, and that transform too many educational institutions from doorways of opportunity into gateways to the criminal justice system.”

He emphasized: “A minor school disciplinary offense should put a student in the principal’s office and not a police precinct.”

Black youth are five times more likely to be jailed than their white peers, according to data from the Annie E. Casey Foundation, and only a quarter of the overall juvenile convictions are for violent arrests.

Tracy Siska, founder and executive director of the Chicago Justice Project, believes that Smart on Crime could not only address youth incarceration but issues of race as well.

“Theoretically, the kids that bear the brunt the greatest of drug crimes and mandatory minimums and things like that are overwhelmingly kids of color in urban settings,” Siska said. “So if the reform is applied evenly, they should impact probably most strongly urban kids of color.”

Siska acknowledges that there’s no way to know if the reforms have the intended effect until they are put into practice, citing marijuana tickets as a failed example of a reform intended to reduce drug-related arrests.

“While the ticketing option was supposed to reduce the number of arrests, it didn’t,” he said. “It only increased the number of tickets. It only increased the number of people involved in some sort of criminal justice oversight.”

He is, however, optimistic about the Smart on Crime reforms.

“For some kids, it means they won’t serve a long, ridiculous sentence for non-violent crimes,” he said. “For some, hopefully, it won’t put them into the criminal justice system at all. Maybe it’ll just increase the number of kids that are put into drug courts and alternative treatment. There are all kinds of really good possibilities that could come out of this.”

But there’s some concern that the reforms won’t reach juveniles without further state-level action, especially since most youth offenders are in state systems and won’t be directly affected by reforms coming from the Executive branch.

“We’re pleased that (Holder’s) making this call and it could have an impact, if Congress does make a move,” said Benjamin Chambers of the National Juvenile Justice Network. “The direct impact isn’t going to be huge, but having someone of his stature take a stand is big on its own.”

There’s little hope, however, that the gridlocked Congress will move on legislation advancing the administration’s reforms. A bill introduced by Sens. Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Mike Lee (R-Utah) to ease mandatory sentencing rules hasn’t moved. Neither has a bill introduced by Sens. Patrick Leahy (D-Vt.) and Rand Paul (R-Ky.) giving judges more lenience in federal criminal cases to avoid mandatory minimums, although it is expected to get a hearing this fall.

Forty-seven states, however, have enacted or begun experimenting with some youth-oriented reforms, as detailed in a 2012 NJJN report. Those range from boosting prison alternatives like community-based treatment or lightening zero-tolerance expulsion policies to keep more students in school.

Those reforms offer a possible path forward, said Jody Kent Lavy, national coordinator at the Campaign for the Fair Sentencing of Youth, as does a DOJ task force on children’s exposure to violence. A task force report released in December found that two out of every three children were exposed to violence or abuse, making them more likely to be violent in the future.

Among the recommendations in that report was that youth be screened for exposure to violence upon entering the prison system and prosecuting youth outside of the adult system “whenever possible.”

That helped the rate of youth incarceration drop by 40 percent over the last 15 years, according to the Annie E Casey Foundation. Kent Lavy said that policies can help get youth out of the adult justice system and avoid life sentences without parole and instead promote redemption programs. But any reform must also touch on the so-called “school-to-prison” pipeline endemic in some communities, which Holder also mentioned in his speech.

“This is a good opportunity for us to look at how young people are affected by violence and how we hold them accountable for their crimes,” she said. “We can’t overstate the significance of the attorney general saying there are needs for significant reforms within the criminal justice system. It’s frankly encouraging to see the administration taking a leadership role on this.”