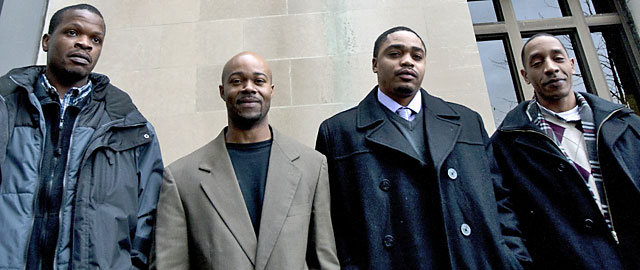

Photo by the Innocence Project

Justice came slowly for the “Englewood Four.”

Seventeen years after being convicted and imprisoned as teenagers for a rape and murder they did not commit, they were finally cleared by a judge.

During interrogations, all four had falsely confessed to the 1994 rape and murder of a 30-year-old prostitute in the Englewood neighborhood on Chicago’s South Side.

Last November, the Englewood Four – Michael Saunders, Harold Richardson, Terrill Swift and Vincent Thames – filed federal lawsuits claiming they were framed by police even though no physical evidence linked them to the crime and DNA evidence from the victim, which later matched that of a man who had killed two other prostitutes, had exonerated them.

The lawsuits alleged police used deceit, intimidation, threats, “prolonged isolation” and “outright physical coercion” to get confessions from the teens. According to the lawsuits, one teen’s chest was pounded with a phone book and a flashlight, and another teen was threatened with being shot behind the police station unless he confessed.

Today, false confessions by juveniles still occur with alarming frequency, experts say. The confessions typically come during high-pressure interrogations when the youths are sometimes subjected to physical abuse, threats, intimidation and suggestions the criminal justice system will go easier on them if they confess.

Juveniles are particularly vulnerable to the pressures of an interrogation, even when it’s conducted legally and without abuse, Joshua Tepfer, co-project director at the Center on Wrongful Convictions of Youth at Northwestern University Law School, told JJIE.

“When you’re that age, can you ever imagine that words that you agree to say knowing they’re not true can put you away the rest of your life?” Tepfer said. “You’re told that that’s the only way you can get out of that situation. You say, ‘Fine, fine, I’ll sign this piece of paper and I’ll go on my merry way.’”

In the words of Douglas L. Colbert, a professor at the University of Maryland Law School: “Everyone has their breaking point when facing an experienced interrogator, and kids get there sooner than the average adult would.

“When a veteran police interrogator is interviewing a 15- or 16-year-old, the overwhelming advantage goes to the officer, and jurors find it very difficult to disbelieve the officer testifying under oath,” he said.

A new database of more than 1,100 exonerations over the past 25 years shows juveniles are much more likely than adults to confess to crimes they did not commit.

The National Registry of Exonerations, put together by the Northwestern University Law School and the University of Michigan Law School, showed 38 percent of youths who were convicted and later cleared had given false confessions, compared with 11 percent of adults.

Experts note juveniles’ brains aren’t fully developed and that teens tend to be impulsive and less mature than adults. Juveniles often don’t weigh long-term consequences of their actions and can be more easily intimidated than adults, and teens have typically been taught to respect authority figures like police officers.

Samuel R. Gross, a professor at the University of Michigan’s Law School and editor of the National Registry of Exonerations, pointed out there’s a high proportion of false confessions among juveniles and suspects with mental disabilities, for some of the same reasons.

“These are people who are easier to mislead [than adults], easier to manipulate, more trusting, more likely to be afraid, more likely to be confused, more likely to not understand what’s going on, and we see that repeatedly in the descriptions people give after the fact of why they falsely confess,” Gross told JJIE.

“People say things like, ‘After five hours [of interrogation], I’d tell them anything they wanted to hear. ... And, ‘I told them what they wanted so I could go home,’ is probably the single most common thing people say.”

There’s good reason for that belief, Gross says: Youths are often led to believe that if they simply confirm what police tell them they already know, they’ll be allowed to go home.

The U.S. Supreme Court has repeatedly weighed in on the interrogations of juvenile suspects.

In a 5-4 decision in 2011, the high court cited a previous decision that found interrogation can “induce a frighteningly high percentage of people to confess to crimes they never committed.”

“Recent studies,” the court said, “suggest that risk is all the more acute when the subject of custodial interrogation is a juvenile.”

The International Association of Chiefs of Police and the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, part of the U.S. Justice Department, cited the Supreme Court decision in a report last year on interrogating juvenile suspects.

“The juvenile interview and interrogation landscape is undergoing an unprecedented upheaval,” the report stated. “Over the past decade, numerous studies have demonstrated that juveniles are particularly likely to give false information – and even falsely confess – when questioned by law enforcement. Based on this research, court decisions are leading police to question juveniles differently than adults.

“Overall,” the report said, “law enforcement is not adequately trained in interviewing and interrogating juveniles.”

The report made a series of recommendations designed to prevent false confessions by juveniles. Among the recommendations: limiting interrogations to a maximum of four hours; allowing a “friendly adult” such as a parent or attorney to be present; recording interrogations; and avoiding the use of deception, promises of leniency, leading questions and threats.

Other experts have also recommended recording entire interrogations, not just confessions. Currently, 17 states and the District of Columbia have statutes requiring that interrogations involving serious crimes be recorded, and numerous police departments across the country require recording of most interrogations.

Thomas Sullivan, an attorney and proponent of recording interrogations, says among other things, the recordings can be used to determine whether defendants had been given appropriate explanation of Miranda rights, whether interrogators used proper procedures and tactics and whether a suspect’s statements were made freely and voluntarily. The recordings, Sullivan says, reduce the risk of false confessions and, in turn, civil suits and damage awards in favor of wrongly convicted people.

Jyoti Nanda, a professor at the University of California-Los Angeles Law School, said the criminal justice system should go beyond recording interrogations of juveniles and require that all juveniles have a lawyer present at interrogations.

“Children shouldn’t have to invoke the right [to a lawyer],” Nanda told JJIE. “I think there should be a law that every child who has an interrogation has a lawyer present.”

Nanda, who runs a Los Angeles clinic to represent the civil needs of children in detention, said, “What’s so unfortunate is during these interrogations of children, that’s when [interrogators] tell them everything will be fine, but everything will not be fine.”

Pingback: The Grim Realities Of Juvenile Shelters In India: A Dismal Predicament And The Need For Reform To Attenuate Juvenile Injustice – RGNUL Legal Aid Clinic