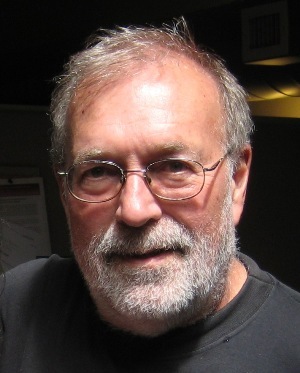

Mike Males

We’ve long heard the theory, from Criminology 101 to the U.S. Supreme Court: teenagers are crime prone (even “deadly”), biologically and developmentally impulsive, peer-driven risk takers, heedless of consequences.

The statistics would seem unassailable: in every culture, ages 15-24 or so have higher crime rates than those 25 and older. Of course, authorities once held that excessive crime by African Americans was an innate feature of primitive racial biology and undeveloped culture.

Unchastened by history, modern theorists have failed to investigate whether “adolescent risks” are explained not by bio-developmental internalities, but by straightforward externalities. Poverty is linked to many high-risk behaviors, and adolescents and young adults are much poorer than older adults.

The Center on Juvenile and Criminal Justice initiated studies investigating this policy-laden question, a tough one since the economic status of offenders must be estimated from the age, race, and geography associated with outcome statistics — a consistent, comprehensive data base but with some methodological challenges. The results of our macro-level analyses of risk outcomes for ages 14-69 were consistent and compelling.

With regard to violent crime, for example, we found that two-thirds of 14-19 year-olds live in areas where youths’ poverty rates top 15 percent, and these areas account for a staggering 86 percent of teens’ arrests. In contrast, just 11 percent of 40-69 year-olds live in areas where middle-aged poverty rivals typical teenaged rates, but they account for 25 percent of middle-aged arrests.

Conversely, just 19 percent of teenagers reside in areas where teen poverty rates average less than 10 percent, but these accounted for just 7 percent of teenagers’ arrests. However, 66 percent of 40-69 year-olds live in areas where middle-agers have poverty rates below 10 percent, accounting for fewer than half of middle-aged arrests.

We found that where teens enjoy low “middle-aged” affluence levels, teens display low “middle-aged” crime, violence, gun homicide, and traffic fatality rates. Where middle-agers suffer high, “teenaged” poverty rates, middle-agers have high crime, violence, gun homicide, and fatal traffic crash rates.

The only difference between teen and middle age with regard to criminal and other risk propensities is that far fewer middle-agers than teens live in high-poverty environments. Teenagers, like Latinos and Louisianans, suffer certain risks because they’re poorer, not because they’re young. We replicated these findings using various years, locales, and outcomes with strengthened results over time.

Our findings were rejected by traditionalists. Three noted authors responded, arguing the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth’s (NLSY) self-reported offending from Wave 1 (1996) to Wave 7 (2003) showed crime peaking around age 15 and declining thereafter, even when self-reported poverty status was held constant.

But this analysis was invalid on its face. The NLSY is limited to a single, outdated cohort (those born in 1980-1984) and contains crippling flaws and inconsistencies. For one, overall crime declined sharply from 1996 to 2003; individuals would report much lower crime rates in 2003 than in 1996 regardless of age or aging. Further, subject attrition in later waves cost Wave 7 a large share of its highest-risk respondents, rendering it incomparable to Wave 1.

For another flaw, socioeconomic status was reported inconsistently by parents for their families (Wave 1), then by young people for their households (Wave 7). For a third, the study’s limited ages, 10-24, enhanced the “college effect” (students often suffer high, temporary poverty along with low crime rates). Yet, its authors posed this lone study confined to 10-24 year-olds employing a messed-up data base as definitive proof that “the age-crime curve in adolescence and early adulthood is not due to age differences in economic status” and constituted a “strong refutation” to our studies of risks spanning ages 15-69.

That teenage crime and poverty are inextricably related has profound implications for policy. We need fewer age-based remediations and more measures to improve youths’ economic status and college access.

American political, medical, and academic establishments took decades to abandon prejudices that people of color are biologically inclined to steal watermelons, Mexicans are innately “hot blooded,” and Native Americans are genetic savages. Likewise, giving up expedient “teenage brain” phrenologies and developmental biases is imperative to refocusing and modernizing juvenile justice.

Defendant age may be legally relevant for other reasons. The United States affords teenagers fewer rights than do other Western nations. Youths denied the adult right to control their environments should not be held as responsible as adults for crime fostered by those environments—an issue that should be drawing far more attention than resurrected 19th century bio-determinism.

Thanks for comments. First, I appreciate Judge Teske’s insights in his response here and hope these will be expressed in future op-eds and in news coverage of his views. I’m submitting another op-ed that addresses these issues, contending that claims about the “teen brain” are not “medical science” and carry dangerous implications. However temporarily politically useful, researchers point out that neuroimagings and brain studies are at far too primitive a stage to connect biology to behavior. The Supreme Court’s Miller and Roper decisions cited much stronger points regarding the systemic denial of juvenile rights in death/LWOP cases that were obscured by unfortunate quips on dubious biodevelopmental notions.

Second, if grownups under equivalent conditions do just as many “incredibly stupid and impulsive things,” how can we keep calling these “adolescent risks”? In particular, African American 50-agers have higher arrest rates than white teens and young adults. Is that because older African Americans are “stupider” than young whites, with less developed brains? No one outside the far right wing would advance such racist demagoguery, even if minor differences in brain structures or processing were found. I’m suggesting that many of the same the mediating factors of poverty, history, policing, etc., on black-vs-white arrest rates—not differential “stupidity”—apply to young-vs.-old arrest rates as well. Isn’t it striking that 73% of juvenile arrests come from areas in which youth poverty rates exceed 20%?

Finally, I’m not advocating that anyone be treated differently because of their socioeconomic status. Practically, however, richer offenders are less likely to be policed, arrested, prosecuted, and sentenced harshly than poorer ones, and so it is likely that middle-agers’ true crime levels are much higher compared to those of teenagers than official statistics (which already indicate juveniles are over-arrested compared to adults) reveal. I realize that juvenile courts see “stupid” youths who apparently are vexing their parents—but over in adult court, you see “stupid” adults vexing their kids. Very often, the same adults and kids.

Mike, I absolutely agree with your conclusion that we must target the child’s socio-economic posture and build supports around those very key protective buffers against delinquency. Afterall, there is a whole set of different research that has been saying that for nearly 40 years within the context of the “What Works” research beginning in adult community corrections in response to Martinson’s 70’s article dubbed “Nothing Works” and now shown to be applicable to adolescents in identifying risk factors and constructing programs narrowly tailored to effectively build those protective buffers. The most difficult construction has been in the area of what you write about, but I caution you to be more discerning in your rhetoric that can come across to those policymakers who wish to place kids back into the electric chair and inject them with lethal chemical (you pick the State) to start quoting your Op-Eds and misconstruing your intention–because I know that is not your intention. Remember, the poverty argument (and I am with you all the way on this!) isn’t what save kids from death and life in prison without parole–and it never will sorry to say. It was the medical fact that kids are still neurologically developing and should be cut some slack. Yes, it’s true–I have used phrases such as “The Age of Stupidity” to describe some adolescent decision-making and thus you label me as a “liberal” attempting humane treatment for kids and “condenscending” and I should broaden my understanding of neuroscience to those after 40 who are now parenting these kids and abusing and neglecting them because of their “stupidity”–citing the explosion of drugs and crime among this adult age group. Now come on Mike, you really think I am that naive? A judge who once served 10 years on the streets of Atlanta as a parole officer and 15 years on the bench also handling abuse and neglect of kids by those 40 year olds and over? Have you not read my Op-Eds about those parents describing exactly what you are saying and the trauma these kids have experienced at the hands of these adults due to their own age of stupidity? Suggestion–change it up just a bit—keep arguing to develop and create solutions to attack the poverty these kids are raised in, but drop the comment that we need fewer age-based remediation. Again, statements like that is what appeals to those many policymakers out there looking for ammunition to support zero tolerance policies in schools and to bring back the detah penalty and life without parole. I get your intellectual presentation, but unfortunately those who hold the power don’t often separate the “wheat from the chaff” as lawyers and judges like to quote. Hey, for your information, my county is the poorest in metro Atlanta–by far. Poverty is all around me here. So, we built a system of care many years ago to build economic opportunity for families and kids in addition to all that other “best practices” stuff and “age-based remediation” so we can avoid stymitizing these young people and putting a yoke around their neck before they reach the so-called “adult” status. This all began in 2002. Since building these programs around all risk factors, including poverty, our juvenile crime rate has decrease 60 percent and our overall graduation rates have increased over 20 percent. Now we are targeting on-time graduation rates, but that’s another story. My point–what we are talking about is a comprehensive strategy. This was not accomplished by developing strategies around our poverty stricken kids and families coming to court, but identifying all their needs. Likewise, I hear what your saying, it’s not enough to address only the cognitive based issues. What I hear you saying is that we need to do better to include improving the socio-economic status of these kids and their families and I am completely on your side. So, I promise to spend more time working in support of convincing policymakers and other practitioners in my field that we must do a better job of addressing the issue of poverty–it is truly a plight our kids suffer by direct and indirect consequences. But please understand that the adolescent brain research does have it’s place in saving kids from death and despair as well. Afterall–it did in Roper and Graham. Now we must take the battle to a much deeper discussion around poverty, but don’t forsake the importance of the still developing pre-frontal lobe of the adolescent brain in protecting kids from the harsh penalties that plague them because policymakers demand toughness. And let’s not forget that these many of these kids living above the poverty line are not in your statistics because the system is harsh on the poor–these medium income and above families have resources and are better equipped to deal with this issue and we never see them in court. Keep in mind that in juvenile justice we can’t find a kid delinquent in need of treatment and supervision if the evidence shows the family is equipped to to take corrective action. I have some appellate decisions reversing judges on this point. But how does this translate to the poor kids who are doing the same things I know at the street level the higher income kids are doing—that’s right, lets open the doors of the court to help these poor people. Let’s label your kid delinquent because he is poor and can’t help himself. Our system of juvenile justice discriminates against poor people and this translate into discrimination against kids of color by the math. All kids, regardless of their race, color, religion, sex and so forth are under neurological construction–there is no discrimination about this. It applies to all kids and should be used to save all kids regardless of their economic status or other difference from unnecessary and abusive laws. I use the adolescent research to convince my colleagues to stop this stupid practice and divert kids to a better system of responding without sending them deeper into a system that makes them worse when instead had we not let them through the door they would have in the least been left to deal with their poverty which is bad enough. In my system, I have allot fewer poor kids being saddled with the abuses of a delinquency system. This means that addressing poverty also means giving these kids in poverty a chance for economic opportunity (should these opportunities be created) by not saddling them with a criminal record in the first place. Call it the”chicken and the egg” crisis I don’t care, but I prefer to attack from both angles at the same time instead of both ends attacking the other and getting no where. Somewhere in between the two should meet.

I couldn’t agree more. Poverty certainly plays into delinquency and criminal behavior. As a practitioner in the juvenile justice field, I see that undeniable fact daily. I also see youth who do not have the life experiences, let alone brains that are fully developed, do incredibly stupid and impulsive things. While I may not be at the 35,000 foot level of researchers, I know that we are dealing with an incredibly complex issue, and that one approach is not going to be sufficient. To think that how we should treat kids or adults should based solely on their socioeconomic status seems very short-cited and I dare say elitist. The war on poverty is much like the war on drugs, a failure. If we are ever going to have a chance to change the trajectory of these families, we will have to approach the issue from multiple angles. While there is definitely a place for a discussion on poverty in the discussion, we shouldn’t ignored other scientifically supported ideas.

THE LAST WORD WAS “an issue that should be drawing far more attention than resurrected 19th century bio-determinism…” I’d like to read more on this subject of “teenage brains” because in my county the bureaucracy and ‘stakeholders’ are buying into this neuroscience story. Please publish something in the near future addressing this… the eugenic social movement was an awful period in the history of ‘science’ and it seems to be making a resurrection. Thanks for all you do.

Thanks for comment, Chris. If you want to see a four-way debate on the “teen brain” issue, with us as one participant, please see Journal of Adolescent Research, January 2009 (24:1) and January 2010 (25:1). I agree, eugenics and biodeterminism have very dangerous implications, and it disturbed me greatly that–after decades of pronouncements asserting hard-wired, biodevelopmental adolescent crime- and risk-proneness–our and others’ extensive searches found no comparative studies on adult and teenage risk-taking mediated by SES. Ruling out disparate environmental factors is routine in comparative social science research; yet, not only had this never been done in adolescent-adult research, many authorities seemed unaware that adolescents as a class are much poorer than older adults. Rather, small and inconsistent differences between teen and adult neurological responses were being interpreted as proof that teenagers are biologically flawed. I will be submitting an op-ed on flaws in “teen brain” assumptions next month.