For more than 25 years, the U.S. Department of Justice has given hundreds of millions in grants to states to reduce the overrepresentation of minority youth in the juvenile justice system, yet youth of color still appear in disproportionate numbers in many areas of the system.

For more than 25 years, the U.S. Department of Justice has given hundreds of millions in grants to states to reduce the overrepresentation of minority youth in the juvenile justice system, yet youth of color still appear in disproportionate numbers in many areas of the system.

According to data from the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention analyzed by JJIE, black youth between the ages of 10 and 17 made up 17 percent of all children in that age group in 2010, but comprised 31 percent of all juvenile arrests, 40 percent of detentions, 34 percent of adjudications (guilty determinations), and 45 percent of cases transferred to adult criminal court.

The percentage of black arrests and adjudications has actually increased in the last 20 years. In 1990, black youth were 15 percent of the entire youth population, but they made up 27 percent of juvenile arrests, 33 percent of adjudications and 40 percent of detentions. The only area that saw improvement by 2010 was in transfers to adult court, where black youth comprised 49 percent of transfers in 1990.

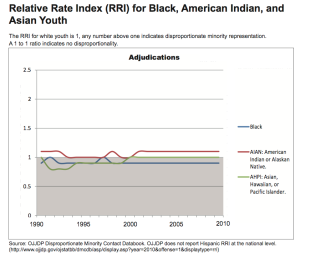

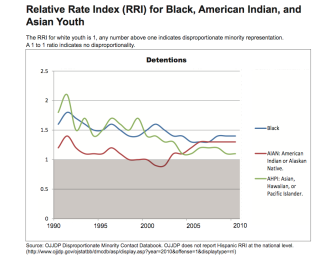

The OJJDP also uses another measurement to determine the level of disproportionate contact for youth of color, known as the Relative Rate Index or RRI, which looks at white youth contact at several points in the system and compares that to minority contact. White contact is assigned the number 1 and anything above 1 would be considered disproportionate or overrepresented. A 1 to 1 ratio would indicate that white and minority youth are appearing at equal rates in the system.

RRI data from OJJDP from 1990-2010 shows that minority youth are still overrepresented in many areas. However, detentions did fall from 1.6 in 1990 to 1.4 in 2010, and waivers fell from 1.7 to 1.4. Adjudications of black youth remained the same at 0.9, but arrests increased from 2 in 1990 to 2.1 in 2010, indicating that arrests of black youth are still occurring at twice the rate of white youth arrests.

RRI data from OJJDP from 1990-2010 shows that minority youth are still overrepresented in many areas. However, detentions did fall from 1.6 in 1990 to 1.4 in 2010, and waivers fell from 1.7 to 1.4. Adjudications of black youth remained the same at 0.9, but arrests increased from 2 in 1990 to 2.1 in 2010, indicating that arrests of black youth are still occurring at twice the rate of white youth arrests.

These numbers may be disheartening to many who work to reduce the disproportionate number of minority youth in the juvenile justice system, especially given that OJJDP has awarded hundreds of millions to states since 1988, when Congress mandated recipients of formula grants have plans to address disproportionate minority contact, also known as DMC. The law was later amended in 2002 to address the disproportionate number of minority youth who come into any contact with the juvenile justice system and are not just in confinement.

Millions Spent

It's impossible to know the exact amount of government funds that have gone toward reducing DMC since 1988 because addressing minority contact is only one of four criteria that states must comply with when vying for formula grants. What's more, once states receive the grant, it's up to them to determine how much is spent on DMC reduction efforts.

To get a general sense of how much money is involved, consider that OJJDP has given more than $600 million in formula grants and other grants that have DMC components from 2007-2013 alone. The agency also spends time assisting states in training, technical assistance and evaluations.

To get a general sense of how much money is involved, consider that OJJDP has given more than $600 million in formula grants and other grants that have DMC components from 2007-2013 alone. The agency also spends time assisting states in training, technical assistance and evaluations.

Although OJJDP gives "strong recommendations" to states on how they should spend their formula grants, the amount devoted to DMC reduction efforts varies by state, said Andrea Coleman, OJJDP's DMC coordinator. Some states allocate 80 percent, while others will set aside 20 percent or 15 percent, she added.

The agency requires those seeking formula funds to follow their DMC Reduction Model, which begins with identifying the extent of DMC using the RRI formula, assessing what's contributing to DMC and implementing plans to reduce DMC through the use of diversion, alternatives to confinement, training or procedural changes. The final phases of the model include evaluating how effective their actions have been, monitoring to see if data reflects changes to DMC and making adjustments based on the data.

The agency requires those seeking formula funds to follow their DMC Reduction Model, which begins with identifying the extent of DMC using the RRI formula, assessing what's contributing to DMC and implementing plans to reduce DMC through the use of diversion, alternatives to confinement, training or procedural changes. The final phases of the model include evaluating how effective their actions have been, monitoring to see if data reflects changes to DMC and making adjustments based on the data.

This model is often far too general, said James Bell, the founder and executive director of the W. Haywood Burns Institute, which works to eliminate racial and ethnic disparity in the juvenile justice system.

"The statute that they're working with says that the OJJDP shall address DMC," Bell said. "OJJDP has gotten much better over time, but when we first started, literally ‘address’ could be you and I go together to a salad bar and talk about it. If I don't want to do anything, what I'll do is address it by giving 10 grand to a professor at a local college to come up with a study, and then put on a conference next year, or maybe an MLK breakfast."

Bell said what's lacking is direction from OJJDP to look at DMC at a local level, in counties, cities, police departments and schools. The agency has also been overly focused on getting communities to learn and calculate the RRI in their community, which Bell said doesn't provide the full picture of inequality.

"You have to analyze crimes in specific communities. Sometimes the problem is not racism or poverty. Sometimes the reason for DMC is they've set up a system that couldn't help anyone," Bell said. "It could be something as simple as when that jurisdiction holds court, whether it’s on a morning calendar or an afternoon calendar."

One of the failings of the federal grant process to reduce DMC is that it's not clear where the money has been spent on a local level, added Alex Piquero, a criminology professor at the University of Texas in Dallas who has researched DMC. Success stories are also isolated, and solutions are hard to extrapolate because what may work in Santa Cruz may not work in Philadelphia or Orlando, he added.

One of the failings of the federal grant process to reduce DMC is that it's not clear where the money has been spent on a local level, added Alex Piquero, a criminology professor at the University of Texas in Dallas who has researched DMC. Success stories are also isolated, and solutions are hard to extrapolate because what may work in Santa Cruz may not work in Philadelphia or Orlando, he added.

"Just because you throw money at a problem, doesn't mean it will solve the problem," Piquero said. "Dollars have to be spent wisely. We need to figure out why these statistics emerge the way they do and spend careful attention on why these kids offend at different rates or for different reasons and how the systems deal with them."

Working with Police

The OJJDP data over the last 20 years clearly shows arrests have the largest level of minority overrepresentation, however OJJDP formula grants don't affect police departments because they are funded through other sources that don't have DMC components. A local police department doesn't have as much incentive to work on DMC reduction efforts as other entities that get OJJDP formula grants, experts say.

It's often difficult for states to build relationships and work with police departments to gain enough trust to allow them to go in and study the issue, said Michael J. Leiber, a criminology professor at the University of South Florida and the former chair of Iowa’s DMC Committee. That's why many of the studies of the DMC mandate have not included police and focus instead on the courts, he added.

"It's up to the police to say I'll let you in," Leiber said. "I'm not defending the police, but they are jumped on all the time for police brutality and racial profiling. They're sensitive about people coming in to study them and feel they would be attacked. For a researcher to get in is very difficult."

OJJDP has recognized that there is a need to focus on the front part of the system, DMC Coordinator Coleman said. It was only until 2002, when the law was broadened to disproportionate minority contact, that OJJDP was able to legally address arrests, she added. Prior to that their efforts were focused on correctional facilities.

Coleman cites an example in Connecticut where the state has looked at DMC arrests since 2005 and developed a training curriculum for patrol officers. Police departments who sent officers to get certified in the training would then be eligible to apply for OJJDP formula grants for police and youth community service projects. The state has seen a 40 percent reduction in black youth arrests since 2006, she said.

"It's only been in probably the last three years that states have really started to concentrate looking at disproportionality in arrests," Coleman said. "I think over the next several years, we'll start to see those numbers come down at the front part of the system."