A short drive outside the downtown of a small east Alabama city, set back from the road among the trees on a low hill, is an unassuming, one-story brick building. The bulky, straight lines of its facade give it the appearance of a 1970s-era post office. The building is unremarkable in almost every way — a physical expression of bureaucracy. A sign near the road reads, “Youth Services.” Affixed to the brick exterior are silver letters that spell “DETENTION CENTER.”

Just inside those walls are boys as young as 10 and as old as 18 who have been charged with juvenile offenses. The kids may stay for months or for just a few hours, but the detention center isn’t meant to be a long-term home. It’s one temporary stop on their journey through the juvenile justice system. By all accounts, it is one of the most progressive detention centers in Alabama. Its administrators and staff embrace openness and transparency. It is rare for a reporter or photographer to be given access to the inside of a detention center, but I was welcomed here.

Past the building’s entrance and its dark glass doors is a small lobby with a few chairs. A heavy steel door divides the world of the free from the world of the detained and those who watch over them. With some reluctance I crossed the threshold of the door and entered the detention center proper.

Past the building’s entrance and its dark glass doors is a small lobby with a few chairs. A heavy steel door divides the world of the free from the world of the detained and those who watch over them. With some reluctance I crossed the threshold of the door and entered the detention center proper.

I was immediately struck by the depression and resignation trapped like bad air inside the cinderblock walls. Although the staff were friendly and appeared to genuinely care about the boys for whom they were responsible, the detention center itself did not reflect this. Dimly lit hallways echoed only the sound of my footsteps. The raucous energy of teenage boys was absent, leaving a disquieting vacuum. The boys themselves were sequestered away, lounging together on worn-out beanbags in a large, dimly lit room, their eyes fixed on a television projecting brightly colored moving images across their expressionless faces.

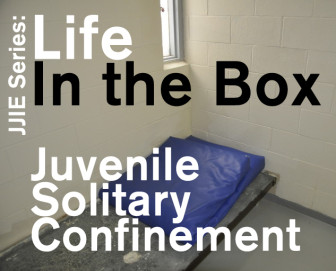

A series of heavy steel doors painted the same dull beige as the wall lined a dim hallway. Stenciled in white spray paint upon each door were the letters “IS” and a number — “01,” “02,” “03” — continuing up to “07.” These were the isolation rooms, where juveniles detained at the center could be sent as punishment for violating the rules, or for protection if they are the target of violence by another youth.

Thousands of young people in the United States are placed in solitary every year. In many detention facilities, juveniles can be kept in an isolation cell for months at a time, or for a single day. During that time they may spend as many as 23 hours a day alone in a small concrete cell, their only human contact with facility staff. Often they are not allowed even a book to pass the time. The cell door may be unlocked once a day for "hygiene" and exercise.

The doors to the solitary cells were open in front of me — no youth were being held in isolation on that day — and I lingered for a moment. The isolation rooms were small and mostly empty. The only objects inside the cell were a metal cot, a thin sleeping mat folded in half on top of the cot and a combined metal toilet and sink in the front corner. A thin, vertical strip of a window, filled with opaque glass, was set in the rear corner, but the room’s light was overwhelmingly fluorescent and unnatural. I stood uncomfortably in the doorway, unwilling to go farther inside. I imagined standing in the isolation cell as the door swung shut behind me. How would I respond if I were locked in here? It was a terrifying thought.

At that moment I realized that no other room in the facility so clearly communicated its own singular purpose. This was a purely punitive space. All the good intentions in the world couldn’t change this, so that even a youth placed in the room for their own protection faced the potential mental harm isolation could cause.

The room was, in fact, designed to be a punitive space. Before it was built someone sat down and drew lines on paper defining the space, and they placed those lines where they did intentionally.

Intention. I’d always considered the word to have a positive connotation. But here I was, presented with the darker side of intention. It was clear that the slim, opaque window had been placed intentionally. The toilet was designed as it was intentionally, and placed where it was intentionally. The same was true of the metal cot, the paint on the cinder block walls and the formidable door that would seal the room off from the rest of the building — and cut off a young person from most human contact. All of these decisions were made intentionally in order to create a room whose sole purpose is to isolate a juvenile from the rest of the detention center, whether as punishment or for safety.

So whose intention led to the design of this room?

I returned home from my tour of the detention center grateful for and fully aware of the fact that I had been incredibly fortunate to avoid time in a similar facility when I was a teenager. Like so many of us, I made my share of poor decisions when I was young. But, whether through pure, stupid luck or because I made those poor choices at a time just before the widespread use of zero-tolerance rules — or maybe it was simply because I was white and middle class — I was never pulled in to the juvenile justice system and I never faced the horrifying prospect of long-term detention or, even worse, isolation.

But the question of intention lingered.

On reflection, my realization that someone has to design juvenile detention centers appears obvious — an example of privileged ignorance, perhaps, or maybe just ordinary naivete. But we must all acknowledge that we routinely take for granted architecture and design. How often do we take time to consider that someone designed our home, our office, the fast food restaurant where we grabbed lunch or the mall in which we shopped for a birthday present? We may rarely, if ever, think about it, but it remains true nonetheless. And it is just as true for the buildings and spaces that we hope never to visit — the prisons, jails and youth detention centers.

And so, like a casual movie fan who takes a film studies class and finds they can no longer watch a movie without analyzing the “mise-en-scene,” I began to see intentional design everywhere, and my thoughts returned to the isolation rooms I’d seen in the Alabama juvenile detention center, and extended to the isolation rooms I’d probably never see in juvenile facilities across the United States.

Isolation, Human Rights and Punitive Architecture

In early 2013, I ran across an essay by architect, activist and Soros Justice Fellow Raphael Sperry in which he argues that architects should cease designing spaces intended for “executions or prolonged solitary confinement.” He calls it a human rights issue.

In his essay, Sperry never specifically discusses isolation rooms in juvenile detention centers. But, I thought, if isolation rooms in adult prisons have the potential to violate human rights it would follow that the same would also be true — if not more true — of isolation rooms in juvenile detention centers.

I asked Sperry about this in a telephone interview. He agreed with my logic, but went one step farther.

“I think it’s possible to say that juvenile halls that are built to the standard of not violating human rights can still be pretty horrible places and wouldn’t live up to the aspiration of human rights, even though you’ve designed them without isolation,” he said.

“There are a lot of things that you can do in juvenile halls that are extremely unpleasant and that make for really bad outcomes for kids,” he said. But even though these things “create a lot of human suffering,” he added, they may not qualify as human rights violations according to standards set by the United Nations and others.

Currently, the American Institute of Architects (AIA) Code of Ethics calls on architects to “uphold human rights in all their endeavors.”

But, Sperry told me, architects shouldn’t be content with only being able to say, “We didn’t violate anyone’s human rights.”

Sperry is president of Architects/Designers/Planners for Social Responsibility (ADPSR), which last year launched a campaign to amend the AIA’s code of ethics to include enforceable language about human rights and building projects. The proposed language would read:

Members shall not design spaces intended for execution or for torture or other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment, including prolonged solitary confinement.

(“Intended” ... There’s that word again.)

Sperry says that not only is the new language more specific, if approved the statement would be included in the code as an enforceable rule instead of the current language’s designation as an “ethical standard,” which is really just an impossible-to-enforce suggestion for professional practice.

"The core of professional ethics for architects revolves around protecting public health, safety and welfare," Sperry said. Additionally this new language would put architects in step with the ethics of medical professionals, which, at a minimum, specifically prohibit participating in executions and torture.

Nevertheless, Sperry’s proposed language raises a question the United States (and at least one recent presidential administration) has struggled with for years: How do we define torture? In fact, how do we define what are human rights? Because one man’s “torture” is another’s “enhanced interrogation techniques.”

For its part, ADPSR accepts human rights standards defined by the United Nations.

“If we are committed to human rights, which is the language the AIA chose [and] which I still support, that links us to the whole international human rights system,” Sperry said. “That means we should take seriously what the United Nations says.”

For example, the U.N. Special Rapporteur on torture, Juan E. Mendez, said the isolation of adults should be used only in the most “exceptional circumstances” and the solitary confinement of juveniles and the mentally ill should be banned outright by all nations.

“Solitary confinement is a harsh measure which is contrary to rehabilitation, the aim of the penitentiary system,” he told the U.N. General Assembly’s third committee in 2011. “Considering the severe mental pain or suffering solitary confinement may cause, it can amount to torture or cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment.”

Before beginning his campaign, Sperry read much of the research cited by the U.N. “about the irreversible psychological damage that people experience when they are in solitary confinement.”

“It’s the denial of any opportunity for any social contact, or any physical contact, that is so painful and cruel, inhuman and degrading,” Sperry said. “And there are elements of the architectural design, especially in supermax prisons for adults, where you see that really borne out in a striking way.”

The U.N. isn’t the only organization decrying the use of juvenile isolation. A 2012 report jointly published by the American Civil Liberties Union and Human Rights Watch, "Growing Up Locked Down," found that because juveniles “are still developing, traumatic experiences like solitary confinement may have a profound effect on their chance to rehabilitate and grow." And a recent letter to U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder, which was signed by 40 advocacy groups, called on Holder to prohibit the use of solitary confinement on youth in federal custody. "The practice is not only cruel," the letter says, "but counterproductive for both rehabilitation and facility security."

Sperry’s campaign to keep architects from designing spaces for isolation or other human rights violations appears to be making headway. An online petition has received some 1,300 digital signatures as of March 13, and at least one local AIA chapter has endorsed the proposed amendment to the code of ethics.

In fact, increased public and political attention has been put on the use of solitary confinement for both youth and adults, so that the ADPSR campaign has become one strong voice in a growing choir. In February, a Congressional hearing explored the possibility of implementing a ban on the use of isolation for certain inmates. Sen. Dick Durbin, D-Ill., called solitary confinement of juveniles “a human rights issue we can’t ignore.”

The Abuse of Spaces

Laura Abrams, associate professor and chair of the Social Welfare Doctoral Program at the UCLA Luskin School of Public Affairs, has worked in residential facilities, many with isolation cells. In 2013, she testified before the California state Senate Public Safety committee about juvenile solitary confinement.

“The use of solitary confinement is not an evidence-based practice in behavior modification or in psychiatric care,” she told the committee. “To the contrary, a robust body of research confirms that isolated confinement can provoke and/or exacerbate severe psychiatric symptoms of psychosis, hallucinations, post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety.”

When I spoke with Abrams she was not aware of the campaign by Sperry and ADPSR to keep architects from designing isolation spaces. I asked her what she thought of it.

“I think that the problem isn’t that there are the spaces; I think the problem is that they’re abused,” she said. However, she added, “some of the spaces are designed to be punitive. They look punitive. I think we have to reorient our thinking toward safety, treatment — but sometimes youth will have to go in those rooms.”

The reality is that juvenile detention facilities can be dangerous places, she added.

“Given that there are times that the youth are at risk of harming themselves or others, and given that are different levels of facilities that handle youth with severe mental disabilities or very violent tendencies, there need to be spaces for youth to be separated from others,” she said. “Sometimes you need to be able to separate the youth who are acting out, and you need to be able to do that in a safe and therapeutic way.”

Psychological support is crucial, she said, including regular visits from a counselor.

Abrams likens it to how a parent responds to an unruly child at home.

“I mean, why do parents send their kids to their rooms? It’s the same principle as that,” she said. “When my kids are feeling out of control I’ll say, ‘You can go up to your room and calm down and in 10 minutes I’ll come up and we can talk about it.’ You give them a time frame and then you follow that isolation with some kind of therapeutic support.”

The problem, she says, is that in corrections that usually doesn’t happen.

Although Abram’s position made sense to me when considered through the pragmatic perspective of someone with experience working inside residential facilities, I couldn’t square it with my own impressions of solitary. I couldn’t imagine how the isolation cells I visited could be ever used for anything other than punishment. How could those hard, sterile rooms, which are designed intentionally for sensory-deprivation, be used therapeutically, even if a young person only spent a brief time inside? I couldn’t see how any counseling that might take place in an isolation cell could result in a positive outcome — the room simply wouldn’t allow it. Only distress and anxiety could survive in that sort of space.

But ultimately it is the isolation that can be so damaging to a young person’s mental health. Even a calm, zen garden theoretically could be used to keep someone isolated from the rest of society. What chance does a room stand when its very intention is isolation? Was this not precisely why the U.N. (and more recently, Sen. Durbin) called for a complete ban on placing youth in isolation cells?

Maybe, Abrams told me, something could be done to remove the stigma and the punitive nature of isolation cells.

In her book, “Compassionate Confinement,” Abrams describes in detail the detention facility in which she conducted a 16-month study. Not far from the facility’s common room is a hallway leading to the youth’s sleeping area, she writes. Along this hallway is:

a single secure cell called the isolation room consisting of a small window, a concrete bed-slab without a mattress, and an exposed toilet and sink. The locked door of this room had a narrow observation window through which the entire room is visible. On our first tour of the dorm, the head of Unit C informed us that the isolation room was used only rarely for youth who were really out of control. Nevertheless, its centrality and visibility (residents walked past the isolation room on the way to and from their sleeping area) clearly made it a looming threat and perhaps the main reminder to us and the residents that this was indeed a juvenile jail.

I tried to recall where the isolation cells were situated in the detention center I visited. They were placed along the hallway leading to the dorms. You couldn’t go to bed at night without passing them.

Blaming the Architect

Perhaps Abrams was correct — that isolation cells were a necessary tool for maintaining the safety of everyone inside a juvenile detention facility, residents and staff included. On a day-to-day basis this could very well be true. But I remembered something Raphael Sperry, the architect and president of ADPSR, told me during our earlier conversation, which I had originally dismissed as an interesting anecdote, confining it away in my reporter’s notebook.

Sperry told me this: “Probably, today, the vast majority of torture and killing — human rights abuses — take place in spaces that weren’t intended for that purpose. In Argentina, the regime in the ‘80s during the dirty war, their number one torture center was an auto repair shop. Nobody’s going to blame the architect of the auto repair shop for it having become [a place of torture].”

Every isolation cell in every juvenile detention center in the United States could be redesigned with calm muted paint colors, cushioned mattresses with soft sheets and blankets, and luxurious, private bathrooms but it wouldn’t matter. Their purpose would remain to isolate the youth from contact with others. And whether that isolation meant for punishment or for safety, it would never change the fact that isolation is inherently mentally damaging to a young person’s still-developing brain.

If the AIA adopts Sperry’s proposed language, the intention of isolation could no longer be assigned to architects. New prisons or juvenile detention facilities built in the country subsequent to the rule’s adoption would be free of rooms intended to be used for isolation or solitary.

But what about rooms or spaces that were not initially intended for that purpose? Couldn’t prison and juvenile detention center administrators simply repurpose some other room in their facility so that it functions as an isolation cell? Freeing architects of the responsibility may simply lay bare the intentions of many in the U.S. criminal and juvenile justice systems.

That remains to be seen. There will always be rooms in which to keep someone isolated, and all of the therapy and counseling in the world won’t change what the U.N. believes and that study after study has shown — that isolation is inherently psychologically damaging. Given that, it would be easy to believe that both Sperry’s campaign to keep architects from designing isolation cells and the solutions included in the California bill for which Abrams testified are half measures at best. But perhaps they are two sides of the same coin. At the very least, they’ve started an important conversation worthy of a national debate.

The treatment is in human worst than the army did in 1942 ww11. I know because I was inthe Military Police. They had rooms 5×8 ft. In Wilmington N. C. Bluethenthal Fighter Plane air Base. Carl T. McDermott 92 ww11 sgt.

Pingback: A Question of Intention and Juvenile Solitary Confinement | Ryan Schill