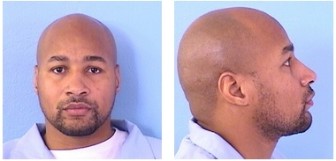

Adolfo Davis, currently in custody in Stateville, Illinois, is seeking retroactive application of Miller v Alabama in his case.

CHICAGO — The Illinois Supreme Court ruled Thursday that Adolfo Davis, who was 16 when sentenced to mandatory life without parole for murder, will be eligible for new sentencing in a ruling that cracks open the door for scores of other inmates convicted while young to potentially live outside of prison as free.

The court’s opinion, issued Thursday morning, also applies retroactively to former cases of inmates sentenced as minors to life with the possibility of parole, even in homicide cases. Retroactivity, which has been adopted by such states as Texas, was something the U.S. Supreme Court left unclear in its 2012 ruling.

Jobi Cates, director of the Human Rights Watch Chicago office, said in a statement: “Youth who commit crimes should be held to account – but in a way that reflects their capacity for rehabilitation…If something is wrong on Tuesday, it was also wrong on Monday. Applying the Miller decision retroactively will help some young offenders find a path to becoming productive members of society.”

The U.S. Supreme Court, in making it’s 2012 decision, agreed with arguments that minors, despite the heinous nature of a crime, could not be held to the same standard and consequences as adults, for the reason that they had not matured emotionally or mentally to the capacity of adult offenders. The court had previously ruled against the juvenile death penalty and juvenile life without parole for crimes other than homicide

The Illinois ruling in a case in which Davis, now 37, was accused of being an accomplice and not the actual shooter, means that about 100 current inmates serving JLWOP could get new hearings and new sentences. But extremely long sentences could still be handed down – just not as a mandatory sentence – if the judge in a case feels it is appropriate.

The fierce battle over how to apply Miller in Illinois – which never adopted a law to apply it and has therefore been out of compliance for almost two years – started even before the Miller ruling. Advocates for both victims of the crimes and minors who committed them – or were accomplices found guilty – fought over who deserved the greatest weight.

Those fighting the Davis ruling argued the victims’ families and loved ones would have endure and relive details of the crimes yet again in new hearings. Juvenile advocates argued for the young perpetrators whose age, combined with the sentence, amounted to what the U.S. Supreme Court said was a violation of the 8th Amendment banning cruel and unusual punishment.

HRW also noted in the statement that, “Sentencing youths under 18 to life with no chance of release is a violation of international law. No other country in the world imposes life without parole on people who are under the age of 18 at the time of their crimes.”