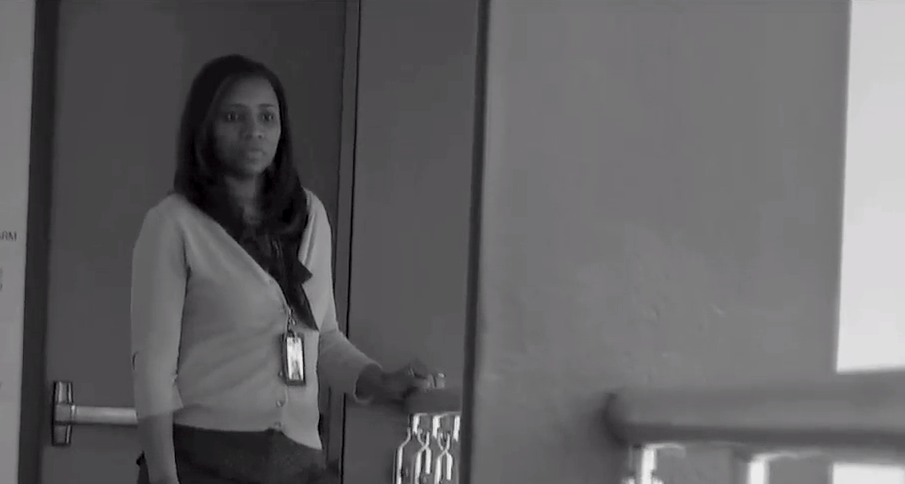

JONESBORO, Ga. — Juvenile probation officer Victoria Harris has an extremely demanding job. It isn’t easy keeping up with 16 teenagers who have found themselves in trouble at home, at school and with the law.

But although her job is difficult, Harris doesn’t show it. She’s vibrant and youthful, lively, with a soft demeanor and a bright, warm smile. Harris is just one of thousands of juvenile probation officers in the United States, and like so many of the others she plays a vital role in the development of the children she comes in contact with. As the direct link between Clayton County’s juvenile court system and its juvenile offenders, Harris is responsible for ensuring that her charges adhere to the court’s rulings.

The Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention estimates that more than half of all juvenile cases brought before a court system result in a child being sentenced to probation. In 2010, there were just under half a million cases that involved a child being placed on probation for some period of time.

As a P.O., Harris must make sure these children go to class and do well in school. She must see to it they come home on time, get along with their parents and stay out of trouble along the way. But Harris does much more than enforce the wishes of the court. In addition to being a probation officer to these children, Harris is a friendly confidante, and, at times, a de facto mother who is there to listen.

Youth probation varies tremendously from state to state and from county to county. Some jurisdictions tend to be more punitive; others are more reconstructive, using their resources for rehabilitation. Clayton County’s Juvenile Court, where Harris works just south of Atlanta, places an emphasis on rehabilitating the children in the hopes that they don’t repeat the mistakes they’ve made. Guidance and drug counseling is provided to youths who need it, and the end goal is to ensure the child has everything they need to get back on track.

Lock-up, Harris said, is typically used as a last resort when all other measures have been exhausted.

“We’re more of a treatment-based court,” Harris said. “We offer alternatives to detention,” adding that punitive-based court systems rarely address the underlying causes of the behavior.

“You’re penalizing the youth without getting to the root of the problem,” she said. Whenever possible, Clayton County’s juvenile court likes to recommend treatment-based alternatives.

These alternatives include providing drug treatment and counseling to the children and families who need it, something Harris said is a far better option than lock-up.

Douglas Thomas, a senior research associate for the National Center for Juvenile Justice, says more and more juvenile courts are moving toward rehabilitative systems of justice when it comes to dealing with children. Diversionary programs are becoming more popular because studies show they have a more positive effect.

“Programs using controlled approaches on average have smaller negative effects on recidivism,” Thomas said. “If you have a program that’s just about coercion and control, incarceration with no treatment component, or boot camps, or Scared Straight. ... Not only do they not work, but there are indications that they have a negative impact.”

According to Thomas, for the best results, care must be taken when choosing an appropriate program for the particular juvenile offender and factors like timing and duration of a program must be taken into account.

“You have to know what that kid’s needs are,” Thomas added.

Harris says her most successful cases are the ones in which the child’s parents are actively involved in their probation.

“When I have very supportive families, the kid is going to make it,” Harris said. “I have to have the parents on board.”

Harris’ coworker Ronaldi Rollins said that Harris is great about getting parents on board with the terms of their child’s probation, not only complying with the rules but actually encouraging them to help the children, something he says makes her a wonderful probation officer.

“She has that caring, motherly, counseling vibe to her,” Rollins said.

Thomas said with the juvenile justice system approaching more treatment-based methods, the role of the modern probation officer is an ever-evolving one.

“You used to have to have the ability to relate to kids, to be trustworthy, to be firm, to be able to have street cred and to be able to enforce the orders of the court,” Thomas said. “But nowadays it’s becoming more sophisticated.”

He said these days a good probation officer must assess the needs of the child to determine what is best for him or her. Much of this, he says, has to do with the P.O.’s background.

Probation officers who have a background in social work, like Harris, tend to focus more on the rehabilitative aspects of probation rather than punitive ones. This, of course, also depends on the juvenile court and which techniques they choose to emphasize.

The more progressive juvenile courts like Clayton County’s tend to use their resources for rehabilitation in hopes that it will reduce the recidivism rates.

“I think it’s all about my approach with them,” she said. “I’m not someone who yells or makes threats or anything. I try to tell them they can be more than what they are right now.”

Financial supporters of The JJIE may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.

Pingback: EEUU(Inglés): The Vital Role of Juvenile Probation Officers | NotiProyecto B