From the Center for Public Integrity

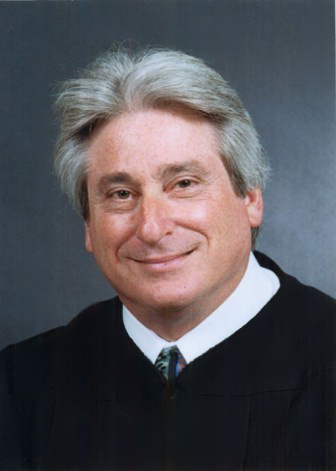

L.A. County Juvenile Courts Judge Michael Nash

Los Angeles’ top juvenile court judge is objecting to a planned diversion of $13 million to school police there from state funds earmarked to provide special learning assistance to disadvantaged kids.

An unprecedented new California funding plan is poised to distribute billions across the Golden State, which has long been beleaguered by inequities in educational support in low-income communities and waves of budget cuts in more recent years. Earmarked funds are supposed to be slated specifically for low-income and foster-care kids, as well as students classified as still learning English as a second language.

In a June 6 letter to the Los Angeles Unified School District, Los Angeles County Presiding Juvenile Court Judge Michael Nash said this particular pot of money should not be diverted to support the L.A. district’s own school police force, which has an annual budget of around $57 million.

Nash expressed “great respect” for recent efforts to reduce school suspensions and referrals to police, but said he did “not see a reasonable nexus between law enforcement and specifically improving the educational experience and outcomes for our most vulnerable student populations.”

“On the contrary,” the judge said, “there has been a wealth of research that indicates that aggressive security measures produce alienation and mistrust among students which, in turn, can disrupt the learning environment.

“This explains why, as part of a nationwide discipline reform process that has gained significant traction of late, there is a specific focus on reducing police involvement in routine school discipline matters,” Nash wrote.

Nash’s letter was made available to the Center for Public Integrity.

Nash presides over one of the biggest juvenile courts in the country and was a recent president of the National Council of Juvenile Court Judges. In that role he also wrote to the White House expressing concerns about schools rushing to obtain federal money to put more school police on campuses in the wake of the 2012 school massacre in Newtown, Conn.

As the Center for Public Integrity reported, Nash has been involved in efforts in Los Angeles to rein in the use of school police on campuses; practices were leading to the annual ticketing of tens of thousands of mostly low-income black and Latino students for tardiness, truancy, schoolyard fights and other minor infractions. Almost half of the ticketed students were 14 or younger.

Nash argues that excessive use of police in essentially school discipline matters — and matters he said were better addressed through counseling and family support — were contributing to a “school-to-prison pipeline” putting kids at risk of greater, not less, trouble with the criminal justice system.

A 12-year-old featured in a Center story was arrested and charged with assault in connection with a fight, his first, with a friend over a basketball game; the school later apologized but the boy had to go to court and also has a police arrest record on the books until he’s at least 18.

Considered the most important school financing reform in 40 years, California’s new so-called “Local Control Funding Formula” general plan will distribute funds per student to districts, along with supplemental money schools are expected to use to address the academic and counseling needs of disadvantaged students.

The state’s black, Latino and lower-income students’ rates of overall graduation or on-time graduation are lagging other groups of students, resulting in disproportionate college enrollment and job skills.

L.A. Unified School District leaders are scheduled to publicly present their draft plan Tuesdayfor how the district will spend hundreds of thousands of dollars extra to boost services for its most vulnerable students. The district’s board must vote on the plan June 30.

A review of other California school districts’ plans shows that some are also considering using money for vulnerable students to supplement school police or security, including in Sacramento, Long Beach and the Kern Union High School District, a Central Valley district with a record of high rates of student expulsion or transfers, as the Center has also reported.

L.A. Unified representatives did not respond to requests for comment on Nash’s letter or the final draft of a spending plan that released over the weekend. The $13 million allotment to support police was unchanged from a previous draft proposal released several months ago.

A chart of proposed spending — posted on the district’s website — is not specific in justifying why school police should receive funding meant to support “school climate” for disadvantaged students. But a more detailed version of the plan does say: “We must point out that there are sometimes serious and legitimate safety issues, such as violence or criminal activity, which necessitate the immediate removal of a student from the campus.”

In another letter to the district in April, a group of legal aid and community groups involved in school-discipline reform in California praised the L.A. district for proposing to direct $37 million of the new supplemental funds to 37 of the district’s most troubled middle and high schools.

But the groups also objected to the idea of diverting more than $13 million to L.A. school police, for the same reasons as Nash. The groups additionally protested that the district’s draft proposal initially allocates only $2.6 million for certain methods of managing student clashes and misbehavior known as “restorative justice” counseling.

Restorative justice methods are key to the L.A. district’s own adopted “School Climate Bill of Rights,” the groups noted. That bill of rights aims to reduce suspensions and referrals of students to police for fights or misbehavior. The relatively modest proposed spending to hire a relative handful of counselors to lead this effort is “extremely disturbing,” the letter says.

The groups asked for many millions more to be invested in such counseling, including all the $13 million slated for police. But no additional money for restorative justice appears in the latest version of the plan.

The letter is signed by the Community Rights Campaign of the Labor Community Strategy Center in Los Angeles and Public Counsel, the nation’s largest pro bono law firm, groups that were instrumental in rolling back school-police ticketing in Los Angeles.

Also signing the letter were the California office of the Children’s Defense Fund; the American Civil Liberties Union of Southern California; the Youth Justice Coalition and CADRE, a parents’ group that has pushed for alternatives to student suspensions.

[Editor's note: Judge Nash is a previous contributor to JJIE.org.]

The Center for Public Integrity is a non-profit, independent investigative news outlet. For more stories on this topic go to publicintegrity.org.