Robert Stolarik / JJIE

The killing of Tayshana Murphy on September 11, 2011 sparked a feud between The Manhattanville Houses and the Grant Houses in West Harlem leaving stretch of a street along Old Broadway a virtual war zone.

NEW YORK — The residents of the Manhattanville and Grant Houses in West Harlem have a new touchstone, a specific moment to organize their collective memory, a way to divide their lives.

Just a month after the New York Police Department conducted the largest raid in the city’s history, the residents who experienced it have a way to refer to their lives in clear “before and after” terms, like old historical abbreviations B.C. and A.D.

In the Manhattanville and Grant Houses there was life before The Raid and life after The Raid. Life has gone on, but it has changed, residents and activists say. To them, life after The Raid has borne witness to undeniable changes. Crime is down, the streets are calmer, the sound of gunshots have, for now, been quieted.

In the Manhattanville and Grant Houses there was life before The Raid and life after The Raid. Life has gone on, but it has changed, residents and activists say. To them, life after The Raid has borne witness to undeniable changes. Crime is down, the streets are calmer, the sound of gunshots have, for now, been quieted.

“Residents feel better about where they live now, about their homes,” said Sarah Martin, 77, who until she resigned on June 16 was for 25 years the General Grant Houses Resident Association president. “They feel like they were expecting a long, hot summer and now they feel it will be problem-free, at least for awhile.”

But for many residents of the two public housing projects, especially families of the arrestees, it has been a disorienting period. They have been contending with mixed emotions left in the wake of the massive show of force that was unleashed by heavily armed officers under the watch of high-ranking police officials the morning of June 3. Even Martin, who welcomes the drop in crime, said she has been torn by how the raid was conducted, and sympathizes with parents whose children face an uncertain future.

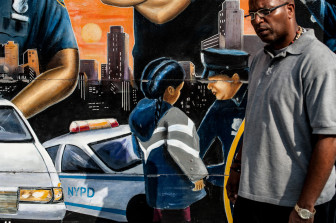

Robert Stolarik / JJIE

The killing of Tayshana Murphy on September 11, 2011 sparked a feud between The Manhattanville Houses and the Grant Houses in West Harlem leaving stretch of a street along Old Broadway a virtual war zone. Taylonn Murphy, father of the slain girl walks past a mural near a police precinct.

On the one hand, they have seen a calm they haven’t seen since basketball star Tayshana “Chicken” Murphy was gunned down in the hallway of a Grant Building in 2011. That shooting rekindled a decades old feud between the Manhattanville and Grant Houses. On the other, a generation of black teenagers and young men — the average age of the 103 already indicted gang members is 22 — have been incarcerated and face charges that could result in spending most of their adult lives in prison. A prospect, they say, that is chilling.

There have been any number of ironies that residents have sorted through in the wake of the Raid. Some of the suspects facing charges on the raid were star witnesses in the Tayshana “Chicken” Murphy case. Both communities are starting to get support and attention from city agencies that are looking to help after the raid — attention residents had been hoping for before the raid. But one bitter unintended consequence produced by the Raid has been the growing enmity it has engendered between the parents and other adult residents from the two houses, where NYCHA estimates more than 7,000 people live.

Community activists say the growing acrimony has made it more difficult for them to forge ahead with grassroots initiatives and reforms to mend the conditions that fueled the feud and led to the Raid in the first place. They say the longstanding feud stems from a lack of resources in the community, especially for young people who have nothing to do and limited job opportunities.

“The young people are a reflection of the older residents — the parents and older residents are pointing their fingers at each other,” Derrick Haynes said, who has for years spearheaded an effort to build a new 24-hour community center for children and teens of both houses. “Now they want to talk about what the police did, and granted a lot of people are right. There are a lot of problems with how that went down, and the kind of response. But! But we have to start doing things different ourselves, and we need to start by working together.”

A month after the historic NYPD gang raids of the Manhattan and Grant Houses discord between the parents and some residents of the rival housing projects has grown worse, making some community activists fear that the chance to repair the rift has grown worse. Behind closed doors, parents from each house will whisper that the real troublemakers were the children from the “other houses.”

A month after the historic NYPD gang raids of the Manhattan and Grant Houses discord between the parents and some residents of the rival housing projects has grown worse, making some community activists fear that the chance to repair the rift has grown worse. Behind closed doors, parents from each house will whisper that the real troublemakers were the children from the “other houses.”

Mothers from Grant will say the teenagers from Manhattanville were the aggressors and that their children were simply defending themselves. Similar allegations are made by parents at Manhattanville. The accusations have inflamed passions, hardened rancorous feelings, and deepened the divide between the two sides.

Taylonn Murphy, Tayshana’s father, has been on the frontlines of the feud between the houses, and he has continued to fight for meaningful change in the communities since The Raid. After his daughter was shot, Murphy joined Haynes -- whose 15-year old brother was the first killing in the feud in 1972 -- and Arnita Brockington, the mother of Tyshawn Brockington, who was convicted in the killing of Tayshana, to end the violence between the houses. He said their efforts have become more difficult since the arrests.

“Getting the parents to work together has been a real mission, a real mission,” an exasperated Murphy said. “The culture at both houses needs to change. We need the parents and the older people working together. A house divided is easier to fall, and that’s what’s happening here after the raid.”

“As parents we failed our kids,” said Sarah Martin, “There is no need for finger-pointing now. It’s my problem, it’s my next door neighbor’s problem, it’s the neighbor who lives upstairs’ problem, and we all need to play a part in fixing it — especially the parents.”

Haynes said internal politics between the houses has complicated the problem. Both houses are sitting on a fund worth $3 million through a “community benefit agreement” issued from the West Harlem Development Corporation. But the money is disbursed in piecemeal chunks to both houses over 15 years.

Leadership from the houses has wanted to create a non-profit to steer the funds into different projects, but that process has proven to be slow. Haynes said the leadership from the houses are not coming together. What is further complicating matters, residents say, is that the city has contracted out operations of the Manhattanville Community Center to a private firm, making some reluctant to direct funds to it.

A few weeks ago, residents and parents of youths arrested in the Raid, stormed out of a meeting at the Manhattanville Community Center. They were frustrated at the lack of clear answers and direction.

Mark Levine, the City Councilman who represents the residents of the houses, said he will stay committed to bringing more resources in the wake of the Raid.

“I need to be more proactive in reaching out to the parents,” he said.

He said he was going to bring in more youth programs, and work with housing leadership to direct some money from the $3 million development fund to fixing up parks, courts and other resources for children and teens.

He said he has not reached out enough to the parents, but promised to do so. He echoed the sentiments of community activists in stressing the similarities residents over the difference in the name on a sign.

“The residents have to understand they have much more in common, by far, than what separates them,” he said.

Haybes agreed, and said just like the youths, the adults are turning on each other despite facing identical challenges.

“It’s an adult version of what’s playing out with the kids,” Haynes said, noting the irony. “These parents are in the same boat — their kids are facing the same charges, they may not see their children for years. These parents are in the same predicament. We need to have cooler heads prevail. We’re hoping to make up some ground with the parents.That will lead to more cooperation and send a signal to both tenant association presidents that they need to work together to solve the problem.”

The discord, he added, has infected the parents of both houses.

“What we’re trying to do is to get them to realize that we have to be solution driven about this problem, because all of these kids are our kids. Whether they come from Manhattanville or Grant. If we as the adults in the situation can’t come together and formulate a strategy for the kids, how do we expect the kids to ever come together?”

Taylonn Murphy agreed with Haynes, and added he is concerned that the moment will be lost if the sharp divisions cannot be undone.

“I’m seeing things and experiencing things that I have encountered since the raid,” he said. “It’s been emotionally draining.”

Martin, the retired Grant resident association president who moved out recently, said the Grant Houses are still “active in her heart” and she wants to see meaningful change happen in both her old home and its rival across 125th Street.

“A lot of time our children were looking for love in all the wrong places. They feel unwanted, unprotected, whatever they’re missing at home they’re seeking in these gang activities. We need to find out what that is and we need to give it to them. We need to find out what’s missing. The raid has made things calmer, but they’re treating the symptom and they’re not treating the disease.”

She said the children she has met are eager to change, and that they are looking for resources, brick -and-mortar, but guidance as well.

“There’s all kinds of kids who want to get involved today, and they’re looking for something,” she said. “But the beat goes on. We have to stop this; we need to be involved in their live to turn these kids around. You take 10 of them off the streets, 20 more will crop up if we don’t.”

Murphy said between hearing the representatives from the district attorney’s office and the NYPD stress that they are a law enforcement agency with a mission to lock people up, and the tension brewing between the parents he is worried that any meaningful change can happen.

“We need to change the mindset of the people. Even if you don’t like me or Arnita or Derrick, our actions show we care about the community. We stopped fights. We headed off violence. We got people talking,” he said. “The police department doesn’t want to get involved on that level. They just clean up the situation. They’re not here to deal with social issues. There are resources to clean up the mess. But they’re not getting here.

He paused and then snorted in disgust.

“These kids,” he said. “It’s like raising lambs to the slaughter.”

Financial supporters of The JJIE may be quoted or mentioned in our stories. They may also be the subjects of our stories.