States face no real federal pressure to reduce racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system, a new report says.

The report by the National Research Council of the National Academy of Sciences, to be formally released in early October, recommends that the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention strengthen a core requirement of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act on reducing racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system.

The JJDPA specifies that states must address disproportionate minority contact (DMC) with the juvenile justice system, but doesn’t say they must reduce it.

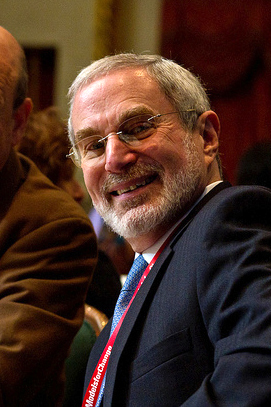

University of Virginia School of Law

Richard Bonnie, LL.B., University of Virginia School of Law, 1969.

Richard Bonnie, co-author of the report, said it calls on OJJDP to require the states to go beyond the “data-collection aspects” and develop specific plans for reducing disparities. “It’s much more of an action-oriented approach to this. …

“I had an opportunity to listen to a lot of people in this field … in terms of their hopes, their expectations, their frustrations,” he said.

Bonnie chaired committees that completed both reports. A professor at the University of Virginia School of Law, he has been working on the reports for about four years.

“There is just widespread concern about disparities — racial and ethnic disparities — in the administration of justice generally and, in particular, in connection with juvenile justice, and I think together with that a considerable level of frustration about why we seem not to be making substantial progress. … It seemed there was a real opportunity here for OJJDP to take a big step forward.”

However, a top juvenile justice official at the Casey Foundation expressed doubt about whether the recommendations would bring about significant change, due to what he called lack of detail and potential political pushback.

OJJDP Administrator Robert Listenbee declined to comment on the new report’s findings, and JJIE’s efforts to arrange an interview with Listenbee through a spokeswoman have been unsuccessful.

Recommendations

A prepublication version of the report, “Implementing Juvenile Justice Reform: The Federal Role” says, “Because OJJDP’s disparities-reduction model only requires identification, assessment, program implementation, evaluation, and monitoring of disparities — that is, it does not actually require states to reduce disparities — very few, if any, states find themselves out of compliance with the core requirement of the JJDPA.”

OJJDP should work with state advisory groups and researchers to look at “decision points” in the juvenile justice system to examine the potential for racial and ethnic disparities, the report says.

States should create data-collection systems on disparities at each of those decision points, such as the first encounter with law enforcement, arrest and detention, separated by race, ethnicity and gender. States should also develop plans for reducing disparities when they’re apparent; evaluate results of those plans; and report the results to OJJDP for monitoring purposes, the report says.

OJJDP should provide more training and technical assistance to help jurisdictions analyze DMC and devise possible interventions. The agency also should highlight and support best practices for reducing DMC and develop learning networks as part of a demonstration grant program. Jurisdictions selected through competitions would partner with OJJDP to identify, document and share reform strategies, under this program, the report says.

“Although the juvenile justice system itself cannot alter the underlying structural causes of racial/ethnic disparities in juvenile justice, many conventional practices in enforcement and administration magnify these underlying disparities, and these contributors are within the reach of justice system policymakers,” the report states.

Bonnie said it’s difficult to sort out how much disparities result from different levels of offending for racial and ethnic groups and how much the disparities are related to different responses to these offenses by the justice system.

But, he added, “Even though you might not be able to untangle those factors … the focus should be on trying to look very, very carefully at the particular policies or practices” in decisions like whether to suspend or expel a child from school or whether to arrest or detain a child.

“It really requires getting very, very specific about each particular practice” to try to determine whether racial and ethnic disparities come into play, Bonnie said.

Radical shift

Mark Soler, executive director of the Washington-based Center for Children's Law and Policy (CCLP), said the report — and OJJDP — have highlighted shortcomings of the agency’s approach to reducing disproportionate minority contact with the juvenile justice system.

David Kindler / Flickr

Mark Soler, executive director of the Center for Children's Law and Policy.

“I think that it’s very important that OJJDP and the National Academy of Sciences recognize and confirm that the approach used thus far by OJJDP has not been very successful in terms of measurable results,” Soler said.

He noted OJJDP has put out requests for proposals for federal grant money to reduce DMC.

“I think that this is a good example of the federal government being responsive to a critical issue in our society that has not been addressed effectively thus far, and I think the approach that the National Academy of Sciences is recommending is much more likely to have a long-term positive effect on these issues than the previous approach,” Soler said.

Liz Ryan, a longtime juvenile justice advocate and the former president and CEO of the Washington-based Campaign for Youth Justice — which seeks to end the practice of trying, sentencing and incarcerating youth under 18 in the adult criminal justice system — said the report’s recommendations would mark a radical shift in OJJDP’s approach to reducing racial and ethnic disparities.

“I think it’s very positive step,” Ryan said. “For many years, the OJJDP has focused on counting kids who are in the system … as opposed to reducing racial and ethnic disparities, and this new piece that’s in here has a very strong focus on reducing racial and ethnic disparities.”

Ryan pointed out that even as arrest and incarceration rates for juveniles have declined significantly in recent years, racial disparities have been rising.

For example, the report noted that based on data from counties with big decreases in incarceration, youths of color represented 67 percent of court dispositions (parole or detention) in 2002, but 80 percent of all dispositions by 2012.

“So it’s even more important now that we redouble our efforts nationally on reducing racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system, and I think this report puts that issue front and center,” Ryan said.

Ryan cited pioneering work on reducing racial and ethnic disparities by the CCLP and the Oakland, Calif.-based W. Haywood Burns Institute as strong models for reform.

Criticism

Nate Balis, director of the Baltimore-based Annie E. Casey Foundation’s Juvenile Justice Strategy Group, said via e-mail: “At the very least, the report points in particular directions (e.g., reducing school-based referrals, taking on detention reform) for which practical, replicable models of practice are available. Unfortunately, the recommendations lack much detail regarding implementation.”

The Annie E. Casey Foundation

Nate Balis, director, Juvenile Justice Strategy Group.

Balis, who oversees Casey’s widely acclaimed Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, pointed to the pervasiveness of racial and ethnic disparities in state and local juvenile justice systems and the challenges in reducing DMC. Given these factors, he said, “Who is providing [the report’s recommended] technical assistance and training may be as important as whether TA and training opportunities are enhanced through greater investments.”

Balis also said the absence of a firm requirement to reduce DMC “was undoubtedly a political compromise reached years ago and sustained until now.”

That likely reflects challenges reducing DMC entails, “especially those elements of the equation (e.g., poverty or social disorganization) that are beyond the immediate control of the juvenile justice system,” Balis said.

In addition, Balis said, there could be significant political pushback if federal funding to states were tied directly to states’ measurable reductions in DMC. But he added that such resistance could be lessened “if the recommended revised approach to this core requirement does, in fact, produce well-documented examples of specific changes in policy, practice and programming that result in measurable reductions” in DMC.

Bonnie, responding to Balis’ assertions, said in an e-mail to JJIE: “No one said it would be easy, but we think this is the way forward. Note that the committee recommends 1) phasing in the changes, 2) including the states as part of the process of making changes and 3) providing training and support during the whole process.”

As for potential responses from the states, Bonnie said: “I am not as skeptical as [Balis] is about the pushback. I think everyone recognizes that the current approach is not accomplishing anything. We need a different approach. Good-faith efforts to identify disparities and try out remedial approaches should not result in loss of funding. Rectifying these problems is a step-by-step process.”

The new report is a follow-up to a 2012 NRC report titled “Reforming Juvenile Justice: A Developmental Approach.”

OJJDP commissioned both NRC reports. The agency funded the first one and helped fund the second, along with the Casey Foundation and the Chicago-based John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation.

Pingback: Viewpoints