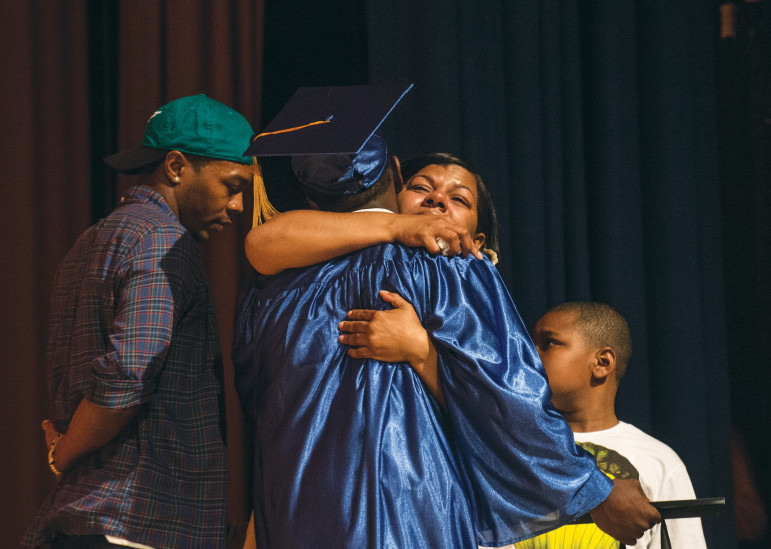

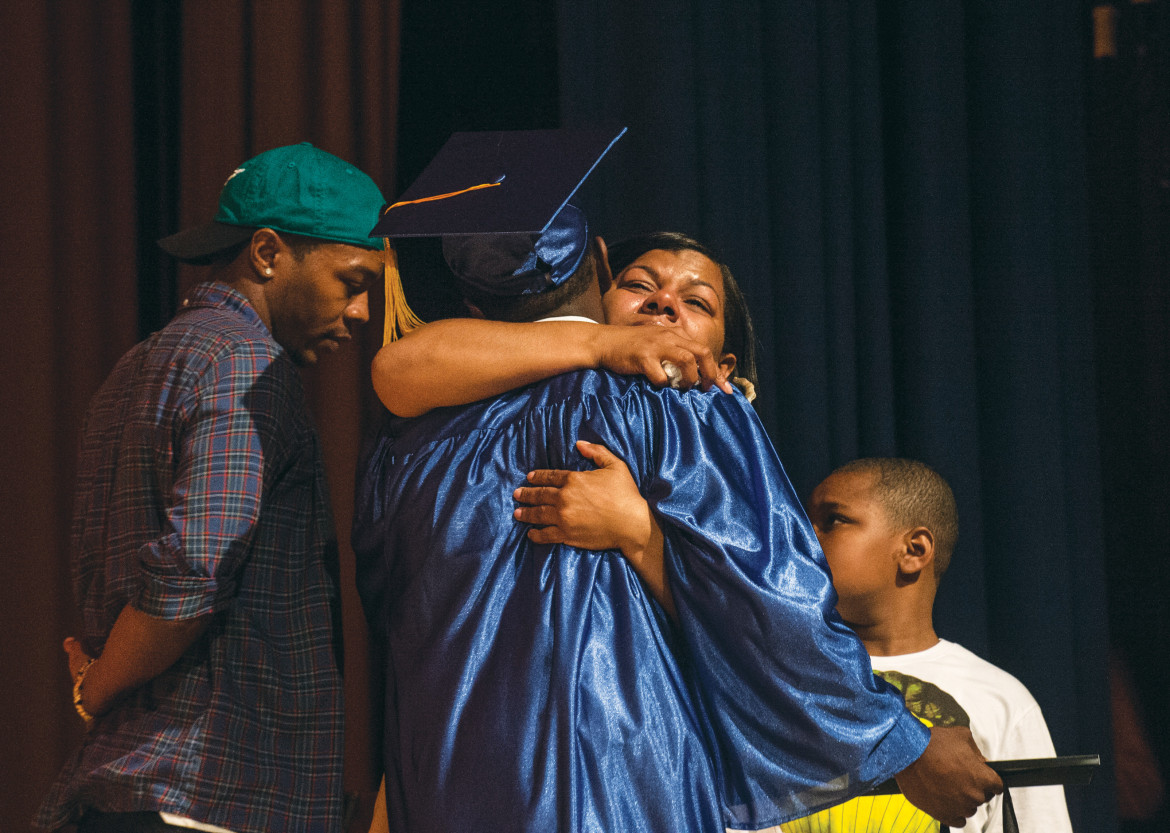

Arlene Ward hugs the first recipient of the scholarship in her deceased son’s name. Resisting revenge, she created the Sadonte Foundation and works to inspire local teens to resist violence, too.

See sidebar "When Kids Are Killed by Police."

NEW YORK — Arlene Ward knew the choice she made that night would change the lives of the young people from the housing projects that define Manhattan’s Lower East Side skyline. She sat in the hospital room where her son’s dead body lay, still warm, a tube jammed down his throat after a gunshot to the chest.

Ward grew up in the projects. When she was a child, revenge was an instrumental part of meting out street justice.

“Our mentality is an eye for an eye,” Ward said. “Someone does something to my son, I go out and get the m----------- who did it.”

Ward’s son, known to friends and family by his middle name, Sadonte, was shot outside of a bodega near his building over a misunderstanding (involving a jacket) between rivals from another housing project.

With a simple, wordless nod, Ward said, she could have ordered some young people to visit the same kind of violence on the people who murdered her firstborn.

“They would have been booted and suited,” Ward said. “And did whatever they had to do.”

Sadonte’s mother (far right) and younger brother (to her right) attend what would have been the teen’s high school graduation.

From revenge to reform

Ward looked at the tear-streaked faces of her son’s friends, classmates, teammates from the baseball team and the children from the Baruch Houses he grew up with. She knew they were in turmoil. She had lost a son, but they had lost their friend.

At that moment, Ward made a commitment to salvage the torment and anguish of losing her son and make some good come out of it. She wanted to turn the pain of her son’s death into something meaningful.

Ward did not realize it at the time, but when she decided to use her son’s murder to change policy, she joined dozens of parents across New York City who have turned away from bloodlust and committed to a similar pledge.

These are parents who decided to resist the desire for revenge and the temptation of losing themselves in their mourning; instead, they saw an opportunity to create change — to save another child from the grave or a prison, and another parent from their pain.

They organize barbecues and picnics, and host screenings of anti-violence films. They put together events filled with face painting and moonbounces dedicated to children and bring in speakers to talk about the real consequences of violence. In small, piecemeal ways, often spending their own money and relying on donations of hamburgers and paper cups, they make a case for policy change so that another parent doesn’t join their unfortunate club.

“With our experience, with us going through this horrific tragedy, we can reach the children, we can reach their hearts,” said Taylonn Murphy, who has dedicated his life to coming up with solutions to violence among youth since his daughter was shot and killed in 2011. “This is real life and we’re living it. This isn’t a job to us. It’s different than a guy sitting behind a desk sorting through statistics.”

He echoed the sentiments of many parents doing this kind of work by pointing out how young people are more receptive to their message.

“They don’t need these real-life stories told to them by the police, or by the district attorney’s office or some bureaucrat from the city,” he said. “These young people aren’t stupid. They feel like those people are coming at them with a different agenda. If the city would help us go out and reach out to these young people in the schools, in the community centers, in whatever forum we can reach them, we could really make change on this whole culture of violence.”

A protester joins a group organized by Malcolm.

Turning passion into policy

In the months after her son was killed, Ward became active. Initially, she opened her doors to the local children still grieving from Sadonte’s death. She counseled them to not give in to their pain by going out into the streets and project courtyards and looking for revenge. She went from counseling Sadonte’s friends to getting organized. She founded the Sadonte Foundation, an organization committed to preventing violence among poor black and Latino teens.

She raised some money for a college scholarship in her son’s name for students at her son’s high school. She worked with the district attorney’s office, hosting screenings of a film called “Triggering Wounds” that illustrates in painstaking detail the consequences of gun violence, down to the damage a bullet can do when it tears through a young body. She organized the “Home Runs, Not Guns” baseball game and cookout to raise money and bring attention to the root causes of violence in poor neighborhoods.

“So many of these parents’ passion is squandered on scrambling to pay for picnics. It’s a waste. This is a club that no one wants to be part of,” Murphy said of these parents of slain children. “But we’re in this club, and we’re trying to make the best of it. We’re definitely overlooked by the city. If we were backed 100 percent in terms of resources, we could change this whole way of thinking about this problem.”

Murphy’s partner, Derrick Haynes, whose teenage brother was shot and killed in the 1970s — the first casualty in a decadeslong feud between residents of the Grant and Manhattanville houses — said he thinks there’s a huge resource the city could tap to help end the problem of violence among youth. He said if the city is serious about finding alternatives, other than raids and mass arrests, it needs to find a way to incorporate these parents into its plans.

“There are so many of us out here with the passion, and the moral authority and the ideas,” Haynes said. “The will is there — we just need resources, infrastructure and some support.”

Haynes and Murphy work to prevent violence from breaking out again between young people in the two rival Houses. They have networked with parents from all five boroughs, as well as Westchester and Long Island, working as a brain trust to share ideas and approaches.

Haynes and Murphy said they have met dozens of mourning mothers like Ward. But, like many parents who are thrust into the position of political activist, she does not have the wherewithal or the resources to turn her passion into a formal outlet for change.

These parents are learning on the fly. They are untrained, unfunded and don’t have the formal infrastructure to turn their passion into policy change.

This disconnect has led to calls from many organizers and politicians to find a way to connect parents’ passion with the organizational capacity of City Hall to make their spirited but novice and sometimes slapdash grassroots efforts more effective. They do not want to see the passion of parents who have the firsthand experience and in many cases concrete plans, wasted on moonbounces.

A club no one wants to join

That night Sadonte was killed, Ward joined what Taylonn Murphy calls the group that no one ever wants to be part of: parents of a child killed by gun violence. Murphy threw himself into activism after his own daughter Tayshana, a promising basketball star, was killed in a feud between rival housing projects in West Harlem.

On the night of April 7 this year, Murphy and Haynes convened a meeting of this club that no one wants to join in a beauty salon in Harlem. They met to discuss pooling their efforts to help bring about change. There were a dozen men and women, mothers and fathers, who had passionate feelings about how to approach the problem of violence among children and teens.

The talk became heated at points, arguing about politics, methods and goals. At one point, as a torrential rain pounded outside, a man came in with a strange smile. It was unclear if he was there for the meeting, so an awkward silence hung in the salon. Finally, Haynes asked the man if he needed something. The man said nothing but took out a collection of blinking trinkets and went up to each parent with the same smile looking for a customer.

“You are in the wrong place for that tonight, brother,” Murphy said to the man.

Haynes escorted the man out. Afterward, they noted with gallows humor how much they could get done if they were sitting at a well-lit conference table in a professionally staffed office, instead of under dormant hair dryers and having their meeting interrupted by a street vendor with blinking trinkets.

“If we were in a conference room instead of a salon, and we had the resources that are necessary to do this work,” Murphy said, “where do you think we would be at this point?”

“To me it’s a no-brainer,” Murphy said. “If a person can deal with the type of tragic events and stress, if someone can deal with all that pressure and all that strain, the passion has to be pushing them to do something extraordinary. This culture of violence with our youth is an epidemic; it’s a crisis. If we’re the antidote, then provide us with the resources for us to be an effective antidote.”

Political culture responds

New York City Councilman Mark Levine has been in the thick of the larger discussion going on about violence among youth. The Grant and Manhattanville houses, where the NYPD conducted the largest gang raid in the department’s history on June 4, fall within his district. He recently attended a public meeting where residents and activists shared ideas on solutions.

Levine has worked with Murphy, Haynes and others in the community looking for ways to channel grassroots energy into tangible policy reform. He has seen parents organize around their child’s death, but has noticed more and more an unprecedented level of passion around gun violence.

“This is something different — many voices speaking loudly about gun violence,” Levine said. “You can’t overstate the power, especially of adults who have lost sons and daughters who have suffered a tragedy and converted their pain into more positive activism. When you look at history, there’s an established playbook of turning tragedy into something positive.”

Levine noted other transformations in political culture that started with a small but determined group of parents racked by tragedy.

“If you look at other major public policy shifts, they’ve often often been brought about by families impacted by a crisis or tragedy. MADD — Mothers Against Drunk Driving — the mothers who started that organization became successful in changing the culture of that crime and the way it is seen.”

Another is Sandy Hook Promise, where some of the parents of children killed in Newtown formed an organization to draw attention to what they see as gaps in national gun laws. Members of the organization declined to comment for this article.

Levine said a similar movement driven by mourning loved ones has led to concrete reform in New York City under the last administration.

“You’re seeing it in New York City in street safety,” Levine said. “The families of pedestrians and cyclists killed in automobile accidents have superenergized the street safety movement — it impacted mayoral policy.”

Levine said the new administration would be open to working with these parents and harnessing their energy.

“I really do think the new mayor supports this movement,” he added. “My sense of Mayor Bill de Blasio's thinking on criminal justice is to truly put a premium on prevention. I look at these type of efforts being crime preventions.”

Arlene Ward’s tattoo is a constant reminder to turn the pain of her son’s death into something meaningful.

An advocate for families

When Shenee Johnson’s 17-year-old son, Kedrick Ali Morrow Jr., who was set to go to college on a scholarship, was gunned down at a high school party in Queens in May 2010, she, too, dedicated her life to transforming the culture of violence that led to his death. She started Life Support, a nonprofit, but she did not initially have training or experience needed to make her organization as effective as it could be.

Johnson, 40, didn’t have the professional support, either, and before her son was killed she was apathetic to politics; but she had the passion, so much so that her new calling as an advocate has led to her divorce. Like many parents of children lost to violence, the passion to work for change can be consuming, and take its toll on their personal life.

“I’m an advocate now. I’m an advocate for families,” said Johnson, who recently took her 9-year-old son on a trip to Albany to deliver anti-violence proposals to Gov. Andrew Cuomo’s office. “I don’t want to be a mother who lost her son to a crime and lives in sorrow. I want to be out there fighting for the families that are left behind.”

Murphy said Johnson is one of the many soldiers in the city whose efforts could be bolstered with support from the city.

“I would love for someone to sit down with us and look at our initiatives,” said Murphy. “We have the staff, the people, we’ve already started our own organizations. We’re tired of being treated like victims by people from other organizations who have not lived through this and who are not out on the front lines with us.”

Like the other parents, Arlene Ward has learned on the job, and has found her new role as an advocate rewarding.

“It’s kind of like therapeutic for me in a weird way. The kids say thank you to me, but I say thank you to them every chance I get,” she said. “They give me purpose. I’m not going to stop.”

On June 24, nearly a year and half after her son was killed, Ward sat in a reserved seat in the auditorium of Facing History High School in midtown Manhattan. Had her son not been killed, it would have been the afternoon of his graduation.

Instead of cheering on Sadonte as he crossed the stage in his cap and gown, she was in front of the students presenting a scholarship in her dead son’s name. As she did, all the students rose in a show of respect. In the crowd, getting ready to graduate, stood some of the same teenagers who waited to follow Ward’s lead the night her son was killed.

See sidebar "When Kids Are Killed by Police."

This story was originally published on our sister site and newspaper Youth Today.

Did you ask to write this story or did you just go because few things starting with .. *A. Delgado *Raphael Ward but hey ..

Pingback: The effect of all this gun talk is real - Brooklyn BodegaBrooklyn Bodega