Melisa Cardona

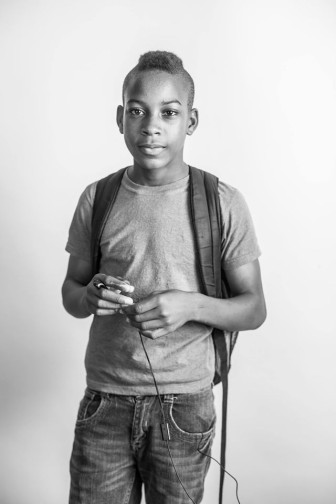

Kids Rethink New Orleans Schools is a youth leadership and youth organizing program that helps students address issues that affect them -- such as the school-to-prison pipeline. This photo was taken at the organization's 2014 Summer Leadership Institute.

Schools should have mood detectors instead of metal detectors, George Carter once observed. The New Orleans student, who turned 15 this year, was a founding member of Kids Rethink New Orleans Schools.

Organized in 2006 in the wake of Hurricane Katrina, the organization seeks to help young people develop a voice in society and in their schools. In 2006, a debate about school reform was swirling in the city.

“Young people were not being consulted in this,” said Thena Robinson-Mock, former executive director of Rethink.

Rethink was formed as a response to encourage kids to think critically about their environment and to become engaged in shaping it.

The organization has clubs for kids ages 10 to 14 located in six New Orleans schools, said Executive Director Karen Marshall.

Rethink also involves older youths ages 15 to 23 in several collectives. Recently, the 14 members of the Rethink Organizing Collective have been fanning out across the city.

“They’ve been trying to get a sense of [young people’s] experiences with school discipline and harassment,” Marshall said. Black kids are constantly policed and controlled, she said.

George was among the kids who worked on a restorative justice committee within Rethink. The group sought school alternatives to suspension and expulsion, which research shows are used disproportionately on African-American students.

Restorative justice puts a focus on relationships between people and often uses a “talk circle” to resolve conflict — based on a practice among indigenous cultures in which each persons talks without interruption. In the discussion, students are asked to come up with constructive reparations when they break rules and cause harm.

The kids of Rethink worked on practicing restorative justice in their own lives as well as advocating it within their schools.

Rethink also published a booklet, “Feet to the Fire: The Rethinker’s Guide to Changing Your School,” available on Amazon.

Another effort of Rethink is its Food Justice Collective, made up of Vietnamese, Latino and African-American young people. They are gathering information right now, Marshall said, by talking to a variety of young people, many of whom live in “food deserts” around the city.

Several years ago, kids in Rethink convinced New Orleans school contractor Aramark to use more locally grown produce in its school lunches. George took part in that effort, which was mentioned in an HBO documentary on obesity.

Building on his interest in justice, George started an internship earlier this year with the Capital Post Conviction Project of Louisiana, which provides legal representation to inmates on death row.

Colin M. Lenton

George Carter joined Kids Rethink New Orleans Schools at age 7. He became a community leader, and had just started an internship with Capital Post Conviction Project of Louisiana before he was shot and killed in October.

He was concerned about making schools safe, said MSNBC correspondent Melissa Harris-Perry, in a TV program this fall. Harris-Perry had become acquainted with Rethink when she attended a conference in New Orleans.

In October, George was shot and killed on a city street in New Orleans.

Members of Rethink had only begun to adjust to this tragedy when another young member, sixth grader Jade Anderson, died in a house fire in November.

“It’s really a deep blow twice in a row,” Marshall said.

Now the adults and kids of Rethink want to carry on their work in memory of George and Jade. In the wake of the house fire, perhaps they will turn their attention to housing, Marshall said, and look at how to make it hospitable, safe and affordable.

The organization is also raising funds for its Summer Leadership Institute. Last year, Rethink expanded to hire six high school interns to plan and facilitate the summer program. The organization plans to continue this program.

For more about Rethink, see the Rethink 2009 documentary.