The Chicago Department of Family and Supportive Services launched Restoring Individuals through Supportive Environments (RISE) at the beginning of this year as an alternative to detention for youths 15 to 17 who have committed misdemeanors. It primarily targets youth from the South and West sides of Chicago, areas that are predominantly African American and Latino.

The Chicago Department of Family and Supportive Services launched Restoring Individuals through Supportive Environments (RISE) at the beginning of this year as an alternative to detention for youths 15 to 17 who have committed misdemeanors. It primarily targets youth from the South and West sides of Chicago, areas that are predominantly African American and Latino.

RISE is a step in the right direction in providing alternatives for justice-involved youth, given the disproportionate rates of juvenile incarceration among black and brown youth compared to their white counterparts.

There is just one problem: Girls are excluded from participating in this program. In fact, no such program exists for justice-involved girls in the state of Illinois.

Through the Juvenile Intervention Support Center (JISC), RISE is a six-month intensive mentoring program that equips youth with leadership development skills guided by a curriculum comprised of civic engagement and restorative justice principles.

The projected goal of the RISE program is to reduce recidivism due to incidents of violence among program participants and to increase their connection to pro-social activities (academics, sports, arts, etc.) and institutions in their neighborhoods (school, community organizations, etc).

This is so even though girls are more likely to be incarcerated for running away, retail theft, disorderly conduct, being a minor requiring authoritative intervention, contempt of court and battery than boys. In fact, girls are statistically more likely to be in the system for misdemeanor and petty offenses than boys (except for misdemeanor status and noncompliance offenses), according to a 2009 study from the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, “Examining at-risk and delinquent girls in Illinois.”

This is so even though girls are more likely to be incarcerated for running away, retail theft, disorderly conduct, being a minor requiring authoritative intervention, contempt of court and battery than boys. In fact, girls are statistically more likely to be in the system for misdemeanor and petty offenses than boys (except for misdemeanor status and noncompliance offenses), according to a 2009 study from the Illinois Criminal Justice Information Authority, “Examining at-risk and delinquent girls in Illinois.”

Overall, the study found girls were underrepresented at all stages of the Illinois juvenile justice system in both the local and federal levels.

Girls who were judged to be delinquent reported suffering inordinate amounts of emotional, physical and sexual trauma in early childhood and adolescence, according to a 2010 report published by Mariame Kaba for Project NIA and the Chicago Taskforce on Violence against Girls and Young Women. Justice-involved girls were also overrepresented in reporting family histories of physical and sexual violence and emotional neglect.

Both reports indicate a connection between trauma exposure and delinquent behavior for girls. Participation in RISE, which provides six months of intensive mentoring, would grant girls increased access to resources that could address their trauma and ultimately reduce their rates of recidivism, one of the program’s primary goals.

To echo law professor Kimberly Crenshaw’s critique of the federal initiative My Brother’s Keeper, “gender exclusivity isn’t new, but it hasn’t been so starkly articulated as public policy in generations.” My Brother’s Keeper supports boys of color but not girls.

Federal policies such as My Brother’s Keeper perpetuate cultural myths such as the Strong Black Woman (or girl), which claims black women are immune to hardship and have a superhuman level of resiliency, and are thus not in need of specific supports.

Crenshaw, founder of the African American Policy Forum, says this is a common belief despite that fact that “black girls have the highest levels of school suspension of any girls and are faced with gender-specific risks such as domestic violence and sex trafficking.”

She also highlights that girls are “more likely to be involved in the child welfare and juvenile justice systems, and more likely to die violently compared to their counterparts.”

If the goal of RISE is to reduce recidivism and increase connection to pro-social activities and institutions for justice-involved youth who have committed misdemeanor offences, girls should be among the targeted population.

This problem is about much more than gender exclusivity in juvenile justice diversion programs. It is about the overall societal devaluation of the lives of girls, which is reflected in this country’s juvenile justice policies. And frankly, this is an act of violence.

If Chicago is committed to supporting justice-involved youth, it cannot afford to exclude girls. The incorporation of girls into RISE would not only communicate to the larger public that Chicago is committed to supporting all its justice-involved youth, but it would also send a clear message to girls: a message that says their lives are worth being restored and that they too are deserving to RISE.

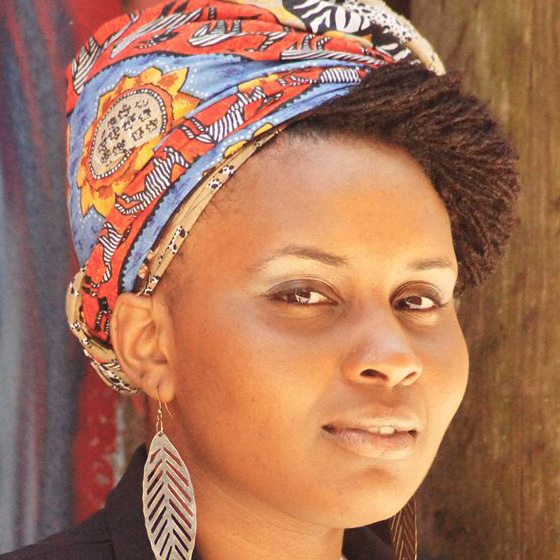

Liz S. Alexander is a womanist social worker, writer and advocate for justice-involved youth. Follower her on twitter @radicalwholenes.

Pingback: Sunday Links, 12/18/14 | Tutus And Tiny Hats

Pingback: Daily Feminist Cheat Sheet