Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Southern trees bear strange fruit,

Blood on the leaves and blood at the root,

Black bodies swinging in the Southern breeze,

Strange fruit hanging from the poplar trees.

(By Abel Meeropol, sung by Billie Holiday)

I approach my first checkpoint before entering the prison. I present my license and inform the guardsmen that I am visiting from out of town. I park my car and join the long line of predominantly black and brown women and their children. I recognize familiar faces from the last couple of times I’ve been here and we greet each other with ours eyes and a smile.

As I approach the window, I take his inmate number out, ready to recite it on command in order to avoid frustrating the officer behind the glass. Unlike the other women, I have not memorized it yet. In fact, I refuse to do so. Even after eight years. I have made a commitment to maintain his humanity, regardless of the circumstances.

“After 18 hours of deliberations, a jury convicted Sammy Cooper*, 21, of aggravated manslaughter in the death of 27-year-old Mike Rhodes, of East Orange, and using a steering-wheel lock to strike 14 blows to his head and face. Cooper, who faces 10 to 30 years in state prison, was also convicted of unlawful possession of a weapon late Tuesday in Newark Superior Court. … Essex County Assistant Prosecutor Frederick Elflein said a taped police confession the day of the March 17, 2007, incident provided strong enough evidence to make this a clear-cut case. ‘The jury paid very close attention,’ he said. ‘Even though in the confession [Cooper] said it was an accident and didn’t intend to kill [Rhodes], it was pretty chilling.’”

On Feb. 4, 2009, The New Jersey Star Ledger published an article, “East Orange man guilty of killing man with steering-wheel lock.” What the article failed to mention is that Sammy Cooper was abandoned by his father after his parents divorced when he was 6; when he was 12 he was incarcerated for a crime he did not commit and was bullied and harassed by the arresting officers. He was later acquitted.

What the article failed to mention was that when he was 15 his mother died unexpectedly and he was the only one of his siblings to become a ward of the state. What the article failed to mention was that he had a mental illness and up until this incident, he himself was a victim. Is still a victim.

No, this does not justify his actions or excuse him from accountability. However, what I find to be “pretty chilling” is the lack of space for the acknowledgement of these other truths; the lack of space to be humanized.

After going through the metal detectors and getting my hand stamped, I join another line and am leaning up against the wall with the other visitors. We are in a colorless room with two guards, waiting to pass through another set of doors to a gym, which serves as the visitation area. When we enter the visitation area, we are permitted the freedom to choose a chair to sit in, the only point at which we the visitors, are permitted to have a choice in the process. I find a chair in the center of the room. A loud buzzer goes off and a flood of black and brown men enter the room. As I wait for my brother, I am overcome by a memory from our childhood.

As children we often dreamed that we would reach a level of fame. We would become household names and be featured on television and in newspapers. As the oldest, it was expected for him to make it to the media outlets first.

And in 2009, my brother made his newspaper debut. Like we fantasized as kids, his name would be listed in bold, mentioned several times in one setting and spoken by powerful people. It was: by the judge, the county prosecutor and the jurors.

Like we fantasized, his name would become household and unforgettable, and it was; in our neighborhood and for the Rhodes family. He, my brother, was 19 when he made his confession and 21 when he was sentenced to serve 22 years of his life in prison. I am reminded that there are consequences to fame.

I spot him as he walks towards me and I call him by name, Sammy; acknowledging and affirming him in all of his humanity.

*Names changed to protect the persons involved.

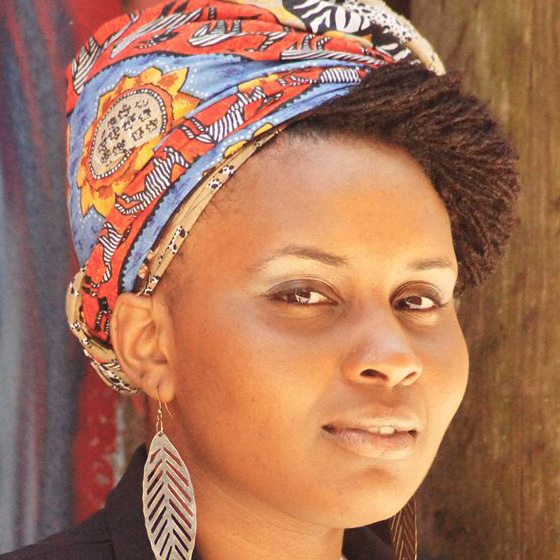

Liz S. Alexander is a womanist social worker, writer and advocate for justice-involved youth. Follower her on twitter @radicalwholenes.