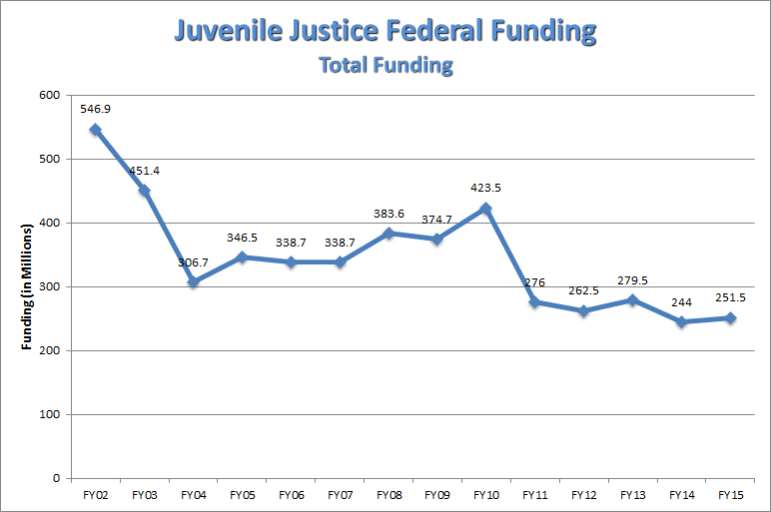

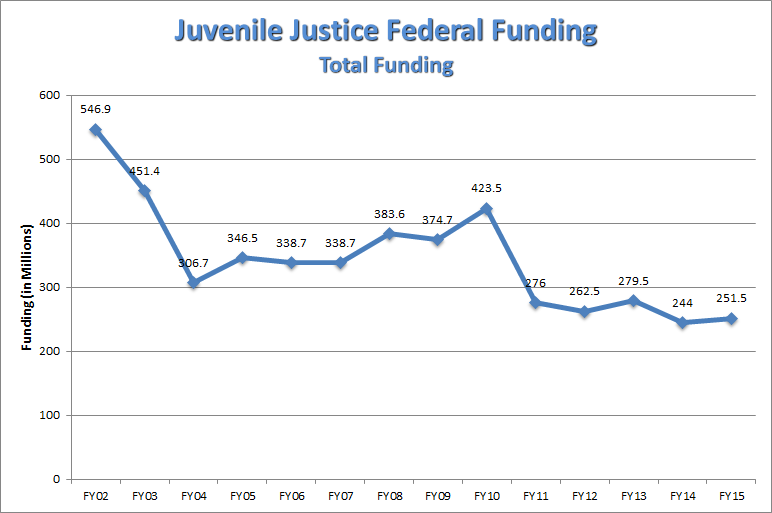

WASHINGTON — When congressional lawmakers last reauthorized the landmark Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act, in fiscal year 2002, they appropriated about $547 million for juvenile justice.

Today, federal spending on juvenile justice totals less than half that amount — about $251 million.

And that, say some juvenile justice advocates, falls far short of needs at a critical juncture for federal juvenile justice funding.

The calls by advocates for more funding come amid signs of possible (and some say long-overdue) reauthorization of the JJDPA this year and soon after a major National Academy of Sciences report urging a radical rethinking of the approach to juvenile justice reform at the federal Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention (OJJDP).

Some advocates said funding levels for formula grants to states to help them comply with standards on the care and custody of youths in the juvenile justice system have declined so much that some states may simply forgo the money and no longer even try to comply with the standards.

That’s an alarming prospect: The standards, or so-called “core requirements” of the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act (JJDPA), aim to prevent detention of “status offenders” who commit nonviolent offenses like skipping school or possessing alcohol; reduce disproportionate minority contact (DMC) with the juvenile justice system; remove youths from adult jails and lockups; and keep youths who are incarcerated in adult facilities separated from adult inmates.

After years of precipitous declines, the formula grants to states, called Title II, now total only about $400,000 each a year for many states, and that’s at a time when bipartisan legislation that would reauthorize the JJDPA is expected to increase states’ compliance requirements, and thus costs.

“If the money goes down, keeps getting smaller and smaller and smaller, to the point where states aren’t getting much at all, then you’re going to have more and more states probably just saying, ‘Never mind, it’s not worth it. You’re not giving us enough money for all the hoops that we have to jump through to get it,’” said Melissa Sickmund, director of the nonprofit National Center for Juvenile Justice, based in Pittsburgh.

“Then you run the risk of going back to the way things were — having more juveniles in jail facilities because it’s convenient, so if a sheriff thinks a kid might be a danger or just looked at him wrong and ticked him off, that kid could go in the adult jail facility with adult inmates in the cell next door, and there would be nothing that would be any kind of [JJDPA] violation. It could mean having status offenders in secure detention because it’s easier to do than to think of something else to do with them. And I don’t think anybody wants to go back to that time.”

Marie Williams

Marie Williams, executive director of the Washington-based, nonprofit Coalition for Juvenile Justice, expressed similar sentiments.

“If one considers the way the JJDPA was conceptualized, the sharp decrease in funding is particularly troubling,” Williams said in an email. “The JJDPA’s design is such that it not only prescribes core protections, but provides funding to incentivize states’ participation in the act, and gives them the resources to do so.

“The significant reduction of those resources over time has had the predictable effect of also diminishing the incentive for some states to participate.”

Williams, whose organization is a coalition of advisory groups in each state or territory that are principally responsible for monitoring and supporting progress in the four core requirements of the JJDPA, added: “Though states undoubtedly want to do right by kids, families and communities by providing the act's core protections, some are beginning to consider whether the JJDPA is all stick and no carrot — requiring compliance with little guidance and even less by way of resources.”

She said CJJ is working as part of the Act 4 Juvenile Justice Campaign, comprising more than 300 organizations, to ensure “appropriations are in line with the needs of the states to improve and modernize their juvenile justice systems and to protect the kids who come into contact with them.”

And John Tuell, executive director of the Boston-based Robert F. Kennedy National Resource Center for Juvenile Justice at the RFK Children’s Action Corps, called the declines in Title II worrisome.

“Some states get so little money from the allocation from the act that I know they’re thinking that it’s not worth it,” Tuell said.

With the spending cuts, he said, “It’s really challenging for OJJDP to be effective and for states to have an incentive to work with OJJDP.”

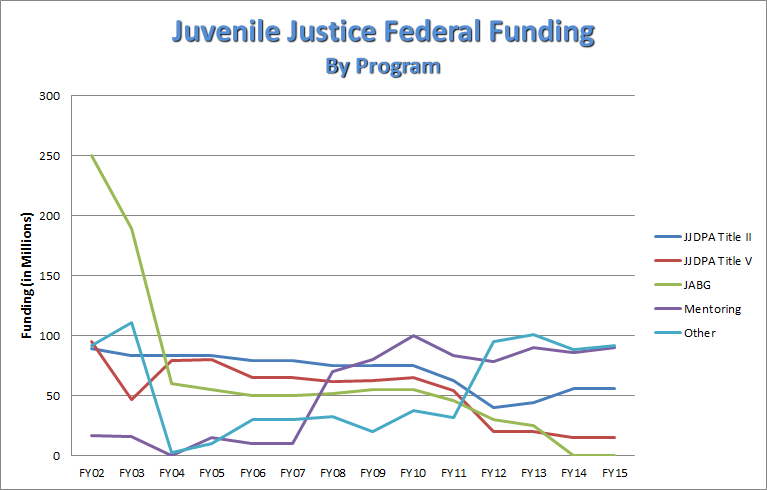

Since fiscal year 2002, federal Title II appropriations have declined from nearly $90 million to about $56 million today (in real dollars, not adjusted for inflation).

During the same period, JJDPA Title V appropriations — designed to prevent delinquency at the local level using “evidence-based” efforts with states and localities providing a 50 percent match — have declined from about $94 million to just $15 million, and almost all of that has been earmarked for non-JJDPA programs.

Juvenile Accountability Block Grants, which had totaled about $250 million in fiscal year 2002, now receive no funding. States had initially used much of this huge block of money for construction of facilities for incarceration. But in more recent years, more of the shrinking pot of available money had gone toward alternatives to confinement for youth involved with the courts.

Another $90 million goes toward mentoring, up from $16 million in fiscal 2002, and about $91 million goes to other programs, including missing and exploited children, community-based, violence-prevention initiatives and grants for helping girls in the juvenile justice system.

Gage Skidmore / Flickr

U.S. Sen. Charles Grassley

A bipartisan measure to reauthorize JJDPA — co-sponsored by Sens. Charles E. Grassley, R-Iowa, and Sheldon Whitehouse, D-R.I. — is expected to be reintroduced soon, and juvenile justice advocates expect it to mirror a version introduced in December, during the last Congress.

The bill would phase out exceptions allowing detention of status offenders, significantly strengthen a requirement to reduce DMC, cut the number of youths placed in adult jails, offer states incentives for relying less on incarceration and improve education for incarcerated youths.

The reauthorization measure calls for a 2 percent annual increase in spending over the course of each of the five years for which it would be reauthorized, but does not give specifics.

"The budget challenges at the Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention are compounded by instances of duplication and overlap in numerous grant programs administered by the U.S. Department of Justice," a spokesman for Grassley said. "Senator Grassley is committed to pursuing reform to ensure that the limited grant resources now available to OJJDP will be devoted to the most meritorious initiatives and projects for the nation’s at-risk youth."

What congressional authorizers call for and what appropriators decide to spend can differ greatly, as juvenile justice advocates well know, and President Barack Obama’s juvenile justice requests have been repeatedly slashed in recent years.

In his fiscal year 2016 budget, released last week, the president requested $339 million for juvenile justice, which would translate to an increase of nearly 35 percent. However, longtime juvenile justice budget observers say it’s doubtful anything approaching that would be appropriated.

Under the proposal, $70 million would go toward Title II JJDPA formula grants; $42 million toward the JJDPA Title V Delinquency Prevention Program, including $10 million targeting the “school-to-prison pipeline”; and $30 million for a new “Smart on Juvenile Justice Initiative,” designed to reduce DMC, recidivism, youth corrections spending and youth contact with the juvenile justice system.

OJJDP Administrator Robert L. Listenbee Jr. said in a statement released through a spokeswoman that Obama’s budget request demonstrates juvenile justice is a big priority.

“This is an issue to which I have a very strong personal commitment,” the statement said. “I believe that one of the most important things we can do to keep communities safe today and for the future is to invest in our kids’ development. I believe the juvenile justice system has a vital role to play in that regard.”

But increasing spending alone wouldn’t necessarily improve outcomes for delinquent children, said Nate Balis, director of the Juvenile Justice Strategy Group at the Baltimore-based Annie E. Casey Foundation.

Balis said more money going toward punitive responses, including incarceration for nonviolent offenders, would lead to worse outcomes.

“More funding in itself for a juvenile justice system that has typically spent the money in the wrong way, on facilities rather than families, on being punitive rather than being developmental in its approach, is not what the juvenile justice system needs,” Balis said.

But, he added: “If the idea is more federal funding for juvenile justice for the right things for the right kids, absolutely, wholeheartedly, sign me up. So definitely, it needs more funding but it needs more funding for the right things.”

Among those things is reducing DMC, said James Bell, executive director of the Oakland, Calif.-based W. Haywood Burns Institute, which strives to eliminate racial and ethnic disparities in the juvenile justice system.

Bell noted the bipartisan reauthorization bill and the Obama administration have called for putting teeth into the DMC core requirement by forcing states not only to track it but also address it.

“Funding becomes a point of emphasis to say that we care,” Bell said. “It’s like anything else: You fund what you care about. We don’t want to have a mandate to reduce it with no help to reduce it.”

Robert Schwartz

Robert G. Schwartz, executive director of the nonprofit Juvenile Law Center in Philadelphia, pointed out the declines in juvenile justice funding have come at a time of growing bipartisan agreement that the juvenile justice system should be more rehabilitative and that mass incarceration has been a costly failure.

Speaking of funding cuts, Schwartz said, “The tragedy of this is that there’s never been more agreement on what works and the importance of prevention and intervention to bring juvenile crime rates down.

“An investment in states to do what they do really well is important and should not continue to decline. And, in fact, anybody who is involved with juvenile justice policy around the country these days knows the importance of increasing these dollars, not decreasing them.”

Pingback: How Communities are Keeping Kids Out of Crime; News Roundup | Reclaiming Futures