As new research emerges on adolescent brain development and trauma, and its association with delinquent behaviors among justice-involved youth, it is apparent that juvenile justice policies should reflect these findings.

As new research emerges on adolescent brain development and trauma, and its association with delinquent behaviors among justice-involved youth, it is apparent that juvenile justice policies should reflect these findings.

In order to do so, mental health professionals need to be at the forefront of policy development.

According to the Justice Policy Institute, an estimated 93 percent of incarcerated youth in the U.S. had experienced at least one traumatic event. In Illinois, home to one of the largest juvenile detention centers in the country, it was reported that 92.5 percent of their youth had experienced one or more traumatic events.

The traumatic experiences reported included sexual abuse, trafficking, community violence, neglect and maltreatment, while physical, sexual and emotional victimization were frequently reported among incarcerated girls.

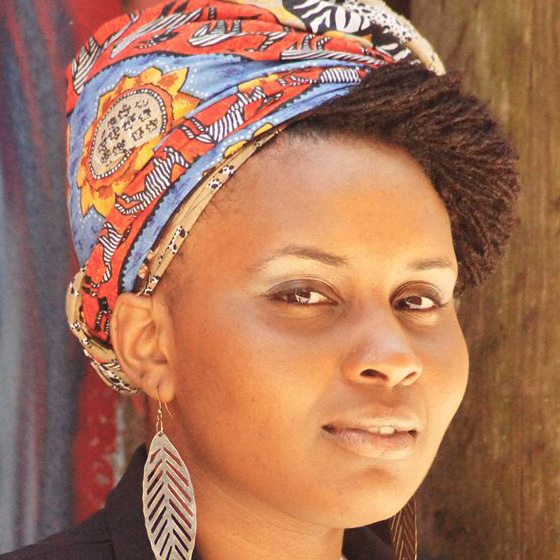

“For this population, the particular experiences of justice-involved youth often include experiences such as early childhood abuse, out-of-home placement, exposure to or witnessing violence, among others,” says Dr. Chanté DeLoach, a clinical psychologist and trauma specialist. “All of these experiences, which are often repeated and cumulative, comprise complex trauma.” And complex trauma has been proven to have damaging effects on the brain, significantly impacting the prefrontal cortex, the area of the brain that regulates impulsivity and judgment.

For adolescents, trauma coupled with their developmental growth period makes them extremely vulnerable and highly susceptible to delinquency, substance abuse and other mental health disorders. In fact, about 70 percent of incarcerated youth were reported to have a mental disorder while 60 percent of incarcerated youth were reported to have a substance abuse disorder.

Although the juvenile justice system prides itself on being a rehabilitative institution for children, the existence of juvenile solitary confinement, for example, says otherwise. What is painfully obvious is that juvenile detention centers are not just housing children who some would consider to likely to have criminal tendencies. Instead, they are housing children who have endured and survived the most horrific circumstances, things that no human being should have to experience.

Simply put, these children don’t need punitive policies that authorize harsh disciplinary action that further traumatize them, they need hugs.

Given these facts, it is only appropriate that mental health professionals, who consist of experts in human development, trauma, substance abuse and mental health disorders, are not just allotted a seat at the table with key juvenile justice policymakers, but have the final say. It is the mental health professionals who have the expertise to implement policies predicated on positive youth development, trauma-informed intervention and humane and rehabilitative practices, all of which serve the best interest of justice-involved youth.

All of which lay the foundation for the path to healing.

Liz S. Alexander is a womanist social worker, writer and advocate for justice-involved youth. Follower her on twitter @radicalwholenes.